The Blues Brothers (1980)

The Blues Brothers ranks among my favorite films of all time — not the best, just a favorite. With inspiration that never remotely comes close to ceasing, John Landis’ wildly over-budget film is more an experience than a conventional movie. It’s a pigeonhole-defying mix of loving homage to rhythm and blues, scattershot comedy, on-the-spot musical, and the most outrageous car chase film ever put to celluloid. It’s a laugh-a-minute destruction derby that defiantly refuses to conform to standard rules of movie-making, frequently transcending the simple story of a band reuniting with religious overtones, wanton destruction, and one of the finest soundtracks to a movie ever. One should have noted the excess that the film would embrace when Aykroyd’s original script, his first, was about three times longer than usual, and this is for a film with lots of musical interludes, mind you. Landis would receive a co-writing credit for helping to pare it down and shape it into something usable.

The film starts out with Jake Blues (John Belushi) being released from prison, picked up by his brother Elwood (Dan Aykroyd) in a used cop car turned “Blues Mobile”. They make good on a promise to visit the orphanage they grew up in, only to find it is in danger of being shut down, due needing $5,000 in tax money owed. With only days to go before it is too late, the Blues Brothers are inspired by a vision from God to save the orphanage, which they plan to do by reuniting the band they played in. This proves to be a tough task, as all of the members have moved on to other occupations. Not only this, but along the way, they manage to piss off the police, the Illinois Nazi Party, and just about everyone else they come across in their bid to make enough money to deliver by the deadline without getting caught, or worse.

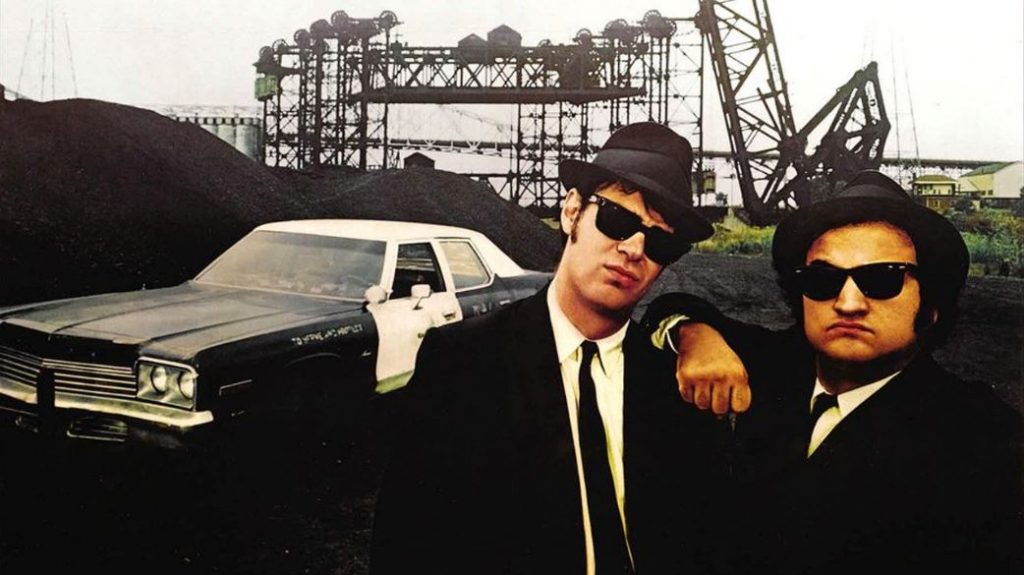

Exuding just the perfect amount of comic cool, Belushi and Aykroyd strut their stuff with confidence, giving oodles of personality to the sketch comedy characters they created during their stint on “Saturday Night Live” in the 1970s. Though the film adheres to its own sense of logic, there are certain constants, starting with the look of the Blues Brothers, who are shown as nearly always wearing their trademark Ray-Ban Wayfarer sunglasses and fedora hats, in addition to their all-black suits and ties. The “Blues Brothers” are quite a talented cover band in their own right, demonstrating their love for the music and attitude of blues and soul, and also the artists responsible for the continued popularity of the genres. Strong cameo appearances are a major strength, with some fantastic musical numbers by James Brown (performing Gospel), Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, John Lee Hooker, Cab Calloway, and, of course, The Blues Brothers themselves. In addition to the musicians are many well-known actors, directors and personalities, including Carrie Fisher (who was engaged to Dan Aykroyd at the time, and , coincidentally, was the host of the original “Saturday Night Live” episode in which the Blues Brothers made their debut).

Belushi and Aykroyd not only deliver on the comedic end, but they also do quite a number as performers, working on some very acrobatic dance moves on stage completely enthrall and entertain as part of their act. Before the Blues Brothers existed, these two were in love with the blues, so much so that they created these alter egos to exemplify that love by delivering on the music that inspired them to sing and play along on their own for so long, originally starting as a warm-up act to get the crowd motivated before episodes of “Saturday Night Live”. They eventually cajoled SNL producer Lorne Michaels into letting them do it live on the air, even though it wasn’t meant strictly as a sketch to educe laughs. You quickly get the feeling it’s not all for show or for money — they actually do love the music they perform, and are so into it they can’t help but be moved to celebrate it with their full bodies and movements.

They were hooked, and felt they had gotten so adept they sought out and obtained a recording contract with Atlantic Records, eventually becoming an opening act for comedian and well-known SNL guest Steve Martin. They just needed to put together a band, which they did with the one that would eventually also appear with them in the movie. Unfortunately, the grind involved with making the movie and doing shows proved to be too much, and in 1979, they announced they would not be returning for another season.

The comedy is so off-the-wall you can’t help but laugh along with its absurdity. The Blues Brothers go on their comic odyssey in deadpan fashion, almost literally leaving behind every stop destroyed, and yet, they seem almost oblivious to it all. Just when you think the madcap nature of the film couldn’t possibly get any more silly, Landis ends the film with almost a half hour of the most expensive, elaborate, and destructive chase sequences ever put on film, very impressive to behold in this era where such things would be rendered largely with CG and heavy editing. Cars speed down the streets of Chicago, get dropped from tall heights, crash in and out of buildings, and pile up on top of each other dozens of times, pulled from the purchase of over a dozen Bluesmobiles and sixty old cop cars at their disposal, leading to its inclusion in the Guinness Book of World Records for most vehicles destroyed in a movie (bested, eventually, by its sequel, before the record would be shattered by a variety of 21st century action blockbusters).

The prolonged scene in which the Bluesmobile and a variety of cops in pursuit smash through a mall was actually shot in a real mall, though it had been closed down at the time of filming (due to too much gang activity in the area) and scheduled for demolition (which didn’t actually occur until 2013). Real stunt people and extras were placed in the renovated-for-one-use mall scene by Landis so that viewers would see that all of the action in the film was shot in real time with real vehicles, and not sped up for effects or done with miniatures or other movie magic. It would famously become the most expensive car chase sequence on film at that time.

The success of the act before and after the film produced three successful albums some of the best in blues, soul and rock-and-roll. Sadly, Belushi’s death in 1982 would put an end to the act, an act that saw Belushi have more access, as well as more need, for the drugs that would keep him going. The Blues Brothers didn’t end completely, though, as Aykroyd will occasionally put a make-shift act together featuring John’s brother, Jim Belushi, and John Goodman to the mix, eventually resulting in a needless and unfunny sequel in 1998 called Blues Brothers 2000, also directed by John Landis, but with lightning unable to strike twice.

Though a financial gamble, it would ultimately prove to be lucrative, cracking the top ten in the U.S. box office for films released in 1980, racking up about $115 million worldwide (off of a budget that ballooned to nearly $30 million), with about half of the overall take coming from overseas sources (especially in Australia, where it was especially popular), which is surprising given that the film has much humor, references, and acts that are distinctly American in appeal. Its screens were much more limited for a movie with its budget, as some movie chains refused to show the film due to its length, had some scathingly bad reviews, and a few Southern theater owners disregarded it as a “black film” not of demographic appeal of those they considered to be their traditional audience. The number one hit of the year, The Empire Strikes Back (released widely the same week, Empire was the top box office earner for the entire theatrical run of The Blues Brothers), also featured Carrie Fisher and Frank Oz, who appears in the opening sequence in a rare acting performance in his human form as the prison clerk who discharges Jake Blues from the joint.

The Blues Brothers is far from a perfect comedy, and can be uneven in spots, but these momentary lapses are very difficult to remember when it’s all over. By the time the credits roll, you’ll most likely have added many fond memories to add to your favorite movie-watching experiences. Easily one of the most entertaining films of its era, The Blues Brothers is a time capsule-worthy collection, not only in irreverent comedy, but also in its reverence for some of the best music of the 1960s and 70s. It’s a beautiful thing.

Qwipster’s grade: A+

MPAA Rated: R for language and violence

Running Time: 133 min. (148 min. extended version)

Cast: John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Carrie Fisher, Henry Gibson, Cab Calloway, John Candy, Charles Napier, Jeff Morris, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, James Brown, Kathleen Freeman, Steve Cropper, Donald Dunn, Murphy Dunne, Willie Hall, Tom Malone, Lou Merloni, Matt Murphy, Alan Rubin, Steve Lawrence, Twiggy, Frank Oz, Steve Williams, Armand Cerami, John Lee Hooker, Steven Spielberg, Chaka Khan (cameo), Stephen Bishop (cameo), John Landis (cameo), Paul Reubens (cameo), Joe Walsh (cameo)

Director: John Landis

Screenplay: Dan Aykroyd, John Landis