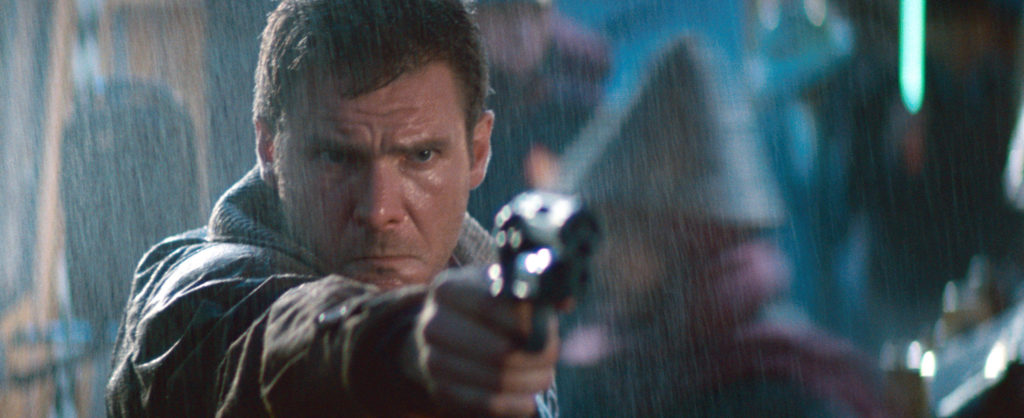

Blade Runner (1982)

The date is November 2019. The city is Los Angeles. Earth has undergone massive population explosions in the urban areas, the city landscape is a mish-mash of every culture, and almost everywhere you go there are advertisements. The most prominent of these advertisements is floating space-barge advertising the Off-World colonies, offering excitement and adventure. It appears there’s much excitement to be true, when six replicants (android-like creations that resemble humans in nearly every possible way, with the exception of enhanced agility and strength, constructed to work as slaves in off-world colonies) commit mutiny and escape to Earth, where they have been outlawed under penalty of death, to find a way to increase their four year lifespan, causing a Blade Runner named Deckard (Ford), a special LAPD task force whose job is to kill any and all replicants, to come out of retirement.

Very loosely based on the 1968 Philip K. Dick novel, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep”, Blade Runner borrows its title from an otherwise unrelated 1974 Alan E. Nourse novel called “The Bladerunner”. William S. Burroughs had been commissioned to write a script treatment for an adaptation of Nourse’s work, which was instead put forward as a novella published in 1979 called “Blade Runner (the movie)”, also unrelated. In these works, the term “blade runner” referred to someone who smuggled medical supplies (such as scalpels). Hampton Fancher, the original screenwriter for adapting the Dick work, happened to have a copy in his possession of Burroughs’ treatment and thought it had a better ring to it than the titles he had associated with his script, namely, Android, Mechanismo, or Dangerous Days. Producer Michael Deeley agreed, so all rights to use the title were subsequently bought out for the movie’s exclusive use, and they applied the term to the android hunters of the movie with no clear definition as to how that term came about, other than it sounded cool.

The impetus for the Dick adaptation started in 1975 when independent film producer Herb Jaffe had been looking into the possibility of turning “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep” into one of his first produced features. Nothing much came of it, mostly due to Dick hating the adaptation done by Jaffe’s son, Robert, which the author claims had been turned into a farcical comedy. (Reportedly, Martin Scorsese had expressed some interest prior to this in the late 1960s, when the book was relatively new, but never secured the rights.) A couple of years later, Hampton Fancher would emerge with a new draft that did get optioned, which focused more on issues surrounding the environment than some of the headier philosophical questions the film is known for today.

After Ridley Scott had originally turned down the film to work on Frank Herbert’s Dune, producer Michael Deeley sweet-talked him into a second-chance offer when that fell through, including a deal that would give the director a cut of the profits. Dustin Hoffman was in serious consideration for the starring role, though he soon fell out of favor once he started insisting on creative changes that he felt would make the film work better, eventually frustrating producer Deeley to seek someone who would work with the material better. After giving a couple of dozen other actors a look (Robert Mitchum (screenwriter Hampton Fancher’s choice, but deemed too old), Martin Sheen, etc.), they eventually came to an agreement with Harrison Ford, after a recommendation from Steven Spielberg, though it would be a very contentious set with Ford and Scott continuously butting heads. Scott had already worked for eight long months polishing up the script with Fancher, so any more changes were treated with skepticism. David Peoples was brought in because of Scott’s difficulty working with Fancher, who had become “too defensive” about his original ideas to compromise, though he was consulted later on a few screenplay revisions.

A few changes though: the setting originally slated to be 1999, though, of course, that was changed to 2019 as the production design would run decidedly more futuristic to push out the events nearly forty years in the future, rather than just seventeen. The location was also slated to be New York City before they dabbled with not naming the city, then eventually settling on Los Angeles, primarily because it is the location of the stylish Bradbury Building (the location of J.F. Sebastian’s abode) and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House (used for both Tyrell’s high rise interiors as well as Deckard’s apartment building), though there are also thematic reasons (the weather in Los Angeles includes perpetual rain and occasional snow, making this seem somewhat implausible).

It only takes a few seconds to get you into the atmosphere of the film, as we watch a breathtaking wide shot of the city, complete with the multicolored neon hues of cars flying through the sky (these airborne vehicles are called ‘Spinners’) among the buildings, all seen through the transposed shot of an eye. Eyes would be a central motif for the film, as they are the key to determine one’s humanity, as well as to capture and reinforce memories. From there, there is a retro-futuristic vibe to the film that blends olf Hollywood stories from forty years before with futuristic Hollywood notions of what the world will be like 40 years later. Rick Deckard is the prototypical film noir detective, complete with stubble, overcoat, and perpetual drinking caused by a life of regrets. What’s different between what we saw in movies of the past and the vision of our future is the blending of the many ethnicities of the city, with Deckard walking through neighborhoods that look distinctly Asian in culture, and characters like the multiracial Gaff talk “Cityspeak”, which blends the languages of Spanish, German, Japanese and Hungarian.

In addition to eyes, another metaphor within the film is chess, in which artificial representations of humankind do battle and the hands of the intellectuals manipulating them for dominance. Roy Batty becomes the manipulator at one point to challenge his maker in Dr. Tyrell, with his gambit gaining him inadvertent access to the heavens to ask for more life. It has been claimed by fans, ones more in the know, that the chess game involves the last three movies of a famous match now dubbed, “The Immortal Game” from 1851, notable not only because it ties in with the desire of replicants to be “immortal”, but also in the great sacrifices they are willing to achieve their goals. Interesting to note from the chess perspective, the name “Roy” in French, means “king”. Scott has gone on to say that all of this was unintentional, however, and others have suggested this is a coincidence because the placement of the pieces on the boards between Tyrell and Sebastian doesn’t even correspond to each other, much less the actual match.

The broader motifs involve mortality, authorship, and God, as humans have anguished over our own mortality and desire to understand our existence. The ending of the film brings forward the notions of angels and higher powers, with the crucifixion alluded to with nails through the palm, a William Blake poem misquote the “Fiery the angels fell…” (“fell” rather than the original poems “rose”) just as the replicants came down to Earth in a fiery display, and the vision of a dove flying to the heavens following one of the more poignant screen deaths in history.

The original theatrical version was released with Harrison Ford performing some voice-over narration, which some claim was a last-minute addition to tie the plot together better. Ford would later say he did the voiceover narration, which was intended in early versions of Fancher’s noir-inspired script but then discarded, very reluctantly, and some have speculated his lifeless reading of the lines was done on the hope they wouldn’t use them. An “International Version” followed closely to this, but with some of the gory violence trimmed down for the American release (though it was released on home video in the United States shortly afterward). After an employee of Warner Bros. discovered a 70mm “workprint” in 1989, the one sent to test audiences that hated the film and prompted the narration and tacked-on ending (that borrowed unused exterior shots were taken during the filming of The Shining) be put on the eventual theatrical release. It was shown for a limited engagement in San Francisco and Los Angeles to great success in 1990 and 1991, respectively.

This prompted Scott to commission a “Director’s Cut”, one that incorporated his suggestions but that he did not have direct involvement in compiling, and release the film more widely into theaters the following year. Despite receiving praise for this cut, which many critics claimed was a marked improvement to the theatrical release, Scott grew dissatisfied with it because he felt it still didn’t adequately represent what he really wanted to do with the film. In 2006, Ridley Scott would claim that a “Final Cut” of the film, which he had been directly tinkering on perfecting for several years, was set to be released into theaters, which it would for a short time in 2007. The Final Cut enhances the effects and soundscape, as well as ties up a few thematic elements Scott desired to make more clear.

**SPOILERS OF SORTS TO FOLLOW** While all of the versions of the film tell relatively similar tales, the main introduction in the non-theatrical cuts is the notion that Deckard himself is might be a replicant, with implanted memories and photographs, created to take down other replicants. While many choose to see the film this way, I find this angle to be problematic, almost to the point of ruining the experience for me thematically, as I feel the contrast between its core human character and his willingness to eventually come to an understanding about life, even among artificial beings, is far more resonant. It also causes the narrative itself to start making less sense, as Deckard is clearly inferior to the replicants in strength, agility, and tolerance for pain. He’s even gets bested physically by Pris, the android created merely as a sex slave. A replicant trying to “retire” other replicants but be vastly inferior to them in nearly every capacity just makes very little sense, especially as they seem to also have designed him to be some sort of alcoholic on top of being outmatched.

Another contrast between Deckard and the other human characters and the replicants is in the way emotions are handled. Deckard is mostly stoic throughout, though he relies on alcohol to cope with some of his stress. The replicants are more childlike because they’re essentially very smart (due to programming) three-year-olds emotionally trapped in adult bodies, causing them to act either playful when they’re happy or lash out with tantrums when something displeases them. The irony is that Tyrell himself claims that replicants have no emotions until they are near the end of their four-year life span and that makes them better suited for slave labor, though the fact that this does not bear as true suggests that either he is using that excuse to sell his product better, or he hasn’t observed his creations as closely over time to see the folly of the statement.

Also, the story arc of the person responsible for killing the replicants undergoes a change that involves empathy by the end of the movie. This incredibly resonant thematic arc on what it’s like to be human, even without the biological definitions, is far more poignant for a human to discover than it would be for a replicant to empathize with his own kind, even if unknowingly. Deckard as a human keeps things clean and tidy and makes narrative and thematic sense. Ford, the screenwriters, and the crew were on board with Deckard as a human; Scott’s interpretation was Scott’s alone, developed midway through the production due to a misunderstanding between the screenwriters until he redid the cut later to make it seem like it could go either way. Deckard as a replicant, while a cool twist to throw out there post facto, makes things messy and opens up far too many questions, and shoots down the themes on humanity and mortality to a less philosophical degree. I can accept human or keeping it ambiguous, but once you define Deckard as definitively a replicant, I would find Blade Runner a good deal less interesting to contemplate.

Author Philip K. Dick would never get to see the finished product, dying on March 2, 1982, just under three months prior to the release of Blade Runner. Dick was initially concerned about the direction that Fancher was going with the material, but did begin to see the promise when the David Peoples’ revision was brought to his attention. Though he didn’t get to see the finished product to see if the film did justice to his book, he had been complementary to the production that he did see on a visit to the set, stating that Scott had captured the look that he had envisioned in the novel. Scott, it should be noted, has stated he never has read the book, which he claimed was too dense.

Blade Runner had been made at a considerable cost, with a budget reported up to about $30 million, making it one of the more expensive films of 1982. Nearly $2 million went to the production design, with even more spent on drawing in Syd Mead to design the futuristic flying cars used within the film. Critics were a bit mixed on the results, putting most of the raise on the atmospheric visuals and set design, as well as giving high notes for its sublime electronic score from Vangelis, but feeling that the story lacked compelling or likable characters or a coherent plot. Its production design and visual effects would earn it two Academy Award nominations (production would go to Gandhi and effects to E.T.). It did score three BAFTA Awards for its costumes, production design, and cinematography.

Because of the cost, Blade Runner would be seen as a failure at the time of its release, making around its production budget, which doesn’t take into account its expensive marketing push. The misleading marketing had contributed to the problems with critic and audience reactions, as it was sold as a big sci-fi action movie, rather than the more contemplative exploration into humanity and mortality by using its setting to better explore these themes metaphorically. It also didn’t help matters that it had the juggernaut E.T. as its competition for its entire run which, in addition to driving people to come out to the theaters for multiple viewings, radically changed what people wanted from their science fiction to be more family-friendly. For years, Blade Runner would be considered a cult movie, eventually a cult classic, and, because of its visual influence and themes regarding artificial intelligence that would be replicated by many other films, it is now firmly established as a classic science fiction film by any standard. An ever-growing amount of film-lovers consider this film to be a sci-fi masterpiece.

You can count me as one of them. Breathtaking visual effects highlight this gorgeous and thought-provoking futuristic film noir tale, with an amazing score by Vangelis. This is more than a simple detective story. It is a multi-layered and profound film that speaks to such weighty issues as humanity, memories, dreams, and a vision of the future that changed the face of science fiction forever. I’m reminded of the scene in 12 Monkeys, where it is remarked by Bruce Willis regarding Vertigo seeming different upon watching it now instead of when he was younger, not because of the movie changes, but because he has changed, and notices different things upon viewing it. Blade Runner is one of those films for me.

My personal pick for the greatest science fiction film of all time.

Qwipster’s rating: A+

Cast: Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Edward James Olmos, Sean Young, Daryl Hannah, M. Emmet Walsh, William Sanderson, Brion James, Joe Turkel, Joanna Cassidy

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Hampton Fancher, David Peoples (based on the novel, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, by Philip K. Dick)