Stargate (1994)

Around 1978, Roland Emmerich, a film school student in Munich, screened a documentary about who built the Great Pyramids of Giza and why. The documentary incorporated ideas from Erich von Daniken’s book, “Chariots of the Gods”, theorizing that technologically advanced aliens influenced human civilizations. As someone obsessed with Ancient Egyptian culture, Emmerich was astonished. These concepts formed the basis of s movie idea that Emmerich dubbed, “Necropole”, set amid the fabled Egyptian city of the dead. His story wasn’t fully formulated, but he did conceive an opening scene: a spaceship is unearthed that had been long buried underneath the Great Pyramid at Giza, discovered after local children lured there go missing. Unfortunately, the German film industry wasn’t able to financially support the sets and effects required, so he shelved it until he had more clout as a filmmaker.

In 1989, Emmerich met Dean Devlin while directing Moon 44. Devlin was not only an actor but an aspiring writer who voluntarily assisted Emmerich with script revisions. During this period, Emmerich discussed his “Necropole” concept and Devlin related his own passion project he called Lawrence of Arabia on another planet. The premise involved a good guy chasing a bad guy who escapes into a wormhole. The good guy hesitates momentarily before following suit, and that brief pause on Earth equates to thirty years passing on the distant planet on the other side, during which the bad guy has set up an evil empire. Nabbing the criminal requires the good guy to inspire the enslaved masses toward revolution.

They became writing partners when Moon 44‘s conceptual artist Oliver Scholl suggested merging their ideas through a “Star Trek” teleportation device. While brainstorming, they screened a retrospective film series on Hollywood’s historical epics hosted by Charlton Heston, including El Cid, Spartacus, and Cleopatra. Heston commented during the presentation that these films couldn’t be made today due to their sheer expense. Devlin and Emmerich viewed that as a challenge. They’d make a grand-scale epic worthy of Cecil B. Demille and would pay homage to sci-fi concepts they loved, including Flash Gordon serials and stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Visual effects technology would supplant the expense of building massive sets or hiring hundreds of thousands of extras.

They entitled their new story “Stargate” due to its teleportation device. Their Stargate was triangular like the pyramids and allowed travel between Earth and an alien planet. After a brilliant child unearths this buried artifact and discovers how to activate it, a team of scientists and military personnel travel through, taking the child so he’d decipher how to return, and find a distant planet where humans are enslaved by aliens.

Once their first script was completed, they shopped it around. Several studios liked it conceptually, but none would commit to financing a film from an untested creative team that would cost over $100 million. Though Emmerich assured them that he’d make it for half that, none believed it.

Initially, their story proceeded chronologically, beginning with the events of 8000 BC. They would save money by keeping events in the present day, using flashbacks to the past when needed. The triangular stargate became circular when Emmerich envisioned chevrons rotating to lock in coordinates that activated the technology.

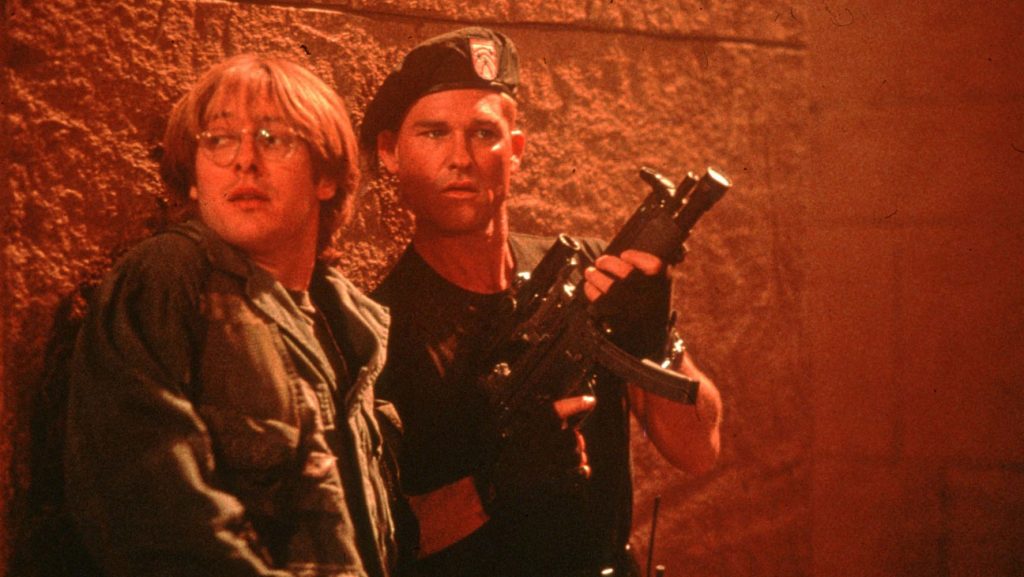

Their final script begins during a burial dig in the 1920s, where a large, metallic, ring-shaped mechanism is found amid the Great Pyramids of Giza. However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that science advanced enough to understand what it is. Needing someone who understood how to read hieroglyphs, a team of scientists enlist Dr. Daniel Jackson, an Egyptologist, and linguist whose theories that humans couldn’t have built the Ancient Egyptian civilization 5000 years ago have made him an outcast in the scientific community. The mechanism, translated as a ‘stargate’, is a gateway to another world on the other end of the known universe. Jackson and a troop of soldiers led by Colonel Jack O’Neil are sent through the stargate to investigate, discovering a civilization similar to Ancient Egypt, lorded over by a strange but powerful figure the Egyptians considered the god Ra.

Despite their revisions, studios began shifting away from sci-fi adventures in favor of straight action. They saw little potential for a movie mixing historical theories with retro sci-fi concepts and old-fashioned adventure. Studio execs only saw it as a blend of “Indiana Jones” and “Star Wars”. Devlin saw it more like 20000 Leagues Under the Sea, where characters traverse from the mundane into wondrous fantasy, with discovery more important than the action. Their agents told them Stargate was a lost cause and to move on to other projects. However, the duo determined they’d rather risk failure with an original concept they believed in than a derivative one they didn’t. They insisted Stargate would be made, and without compromising their vision.

An opportunity emerged when producer Mario Kassar, co-founder of Carolco Pictures, with whom Emmerich had worked previously on a project for Sylvester Stallone called Isobar that never got made, needed someone to take over the reins of Universal Soldier after firing the previous director, Andrew Davis. Kassar said if they helped him complete Universal Soldier he’d help them make their next project. Indeed, Universal Soldier earned over $100 million worldwide. Also, many within the crew became instrumental in bringing Stargate to life: production designer Holger Gross, visual effects supervisor Kit West, and Mario Kassar himself, an Egyptian art fanatic who decided to executive produce Stargate independently from Carolco, which was suffering financially and couldn’t muster the resources.

Kassar found an agreeable partner in Marc Frydman, who ran Studio Canal Plus, the American production wing of the French pay-TV company. Frydman loved the concept, but couldn’t afford more than $25 million. Devlin disingenuously asserted Stargate was a $25 million picture to make the deal. After further details, Frydman realized it would cost much more, but he was sold and obtained additional partners to increase the budget. To save money, they expanded the pre-production phase to iron out details before production.

Additional financing was provided by Hexagon Films, the American subsidiary of Studio Canal Plus, Emmerich’s production company, Centropolis, plus a mix of French and American banks. At that time, the budget was estimated at between $30-40 million to be shot in Los Angeles and Europe. Canal Plus bought a stake in Carolco to stave off its bankruptcy and would use them for international distribution. However, due to the sci-fi slump, they found no willing partners for U.S. distribution, which made it very risky to proceed.

For authenticity in the Ancient Egyptian dialogue, they hired UCLA professor Dr. Stuart Tyson-Smith to construct the language and serve as a dialogue coach. The language was altered to represent its evolution over ten thousand years. Kassar quibbled that they were wasting time constructing a language no viewers would understand. Emmerich assured him that the sci-fi fans would care.

They approached big-name actors to sell the picture to foreign markets. Among them was Kurt Russell, who was initially offered $2 million. Russell’s agents at CAA (Creative Artists Agency) pushed back on the offer. This was not only half Russell’s going rate but they also represented two other actors that they knew had been offered much more, Sean Connery and Wesley Snipes, who received $12 million and $9 million offers, respectively. The agents felt Russell should at least be offered as much as Snipes but because Captain Ron fizzled at the box office, he was considered a higher risk. Russell, who hated the script, insisted they’d need a huge offer for him to accept. That huge offer came: $5 million with $2 million in guaranteed deferments. Later, when it was discovered Russell was shown a sketchy draft created just for studios to understand the concept, he quipped that they could have saved millions by sending him a completed script.

Despite his reticence, Russell was looking forward to Stargate. He’d spent four months of consecutive 20-hour days performing emergency reshoots as the uncredited director on Tombstone. Also, Emmerich’s enthusiasm and confidence gave Russell hope it wouldn’t be a disaster. All he had to do was say his lines, even if they were awful. On that, Russell decided it was better to reduce his character’s dialogue. He insisted that it was more credible for a traumatized soldier to internalize his emotions. He winnowed his lines to half of what was scripted. Even though this conceded top billing to his co-star, he rationalized that it was more fun to be Han Solo than Luke Skywalker. Devlin and Emmerich weren’t averse to change; the screenplay went through 47 drafts prior to the shooting script.

For that starring role, they wanted an actor that presented as intelligent while loveably quirky. Emmerich’s top choice of Matthew Broderick was unavailable due to Broadway show commitments. Among others, James Spader declined, citing the script was awful. However, receiving a million-dollar offer, he met with Emmerich, whose boyish curiosity and enthusiasm win Spader over.

Spader quibbled about his character’s bumbling, comical nature. He asserted that there was no way Daniel would be brave enough to step through the Stargate. It made sense when the character was originally meant to be a child because children don’t always understand the danger of pursuing every curiosity. This is what Emmerich wanted: a man with a genius intellect but still retained his childhood impulsiveness and wouldn’t accept failure. Spader later observed that these traits resembled Emmerich’, which gave his performance a base of reference.

Spader enjoyed Emmerich’s flexibility in allowing actors freedom to mold their actions and dialogue within the plot construct. Despite that freedom. Spader had a flare-up once where he refused to come out of his trailer until script issues were fixed. Russell barged into the trailer, reminding Spader that they’d already consented to act in a film that was poorly written by accepting millions of dollars.

Despite six months of auditions, Emmerich was still searching for the female lead, proclaiming he’d know Sha’uri when he saw her. Days before Sha’uri’s scenes were shot, the casting director supplied a videotape of Israeli actress Mili Avital, and it clicked. Fortuitously, Avital was in the United States attending acting school. She was waiting tables when a customer introduced herself as a talent scout and she’d just scored a major role in a $60 million production opposite Kurt Russell and James Spader. The next day, Avital was in Yuma getting prepped for hair, makeup, and wardrobe.

Arthur C. Clarke once said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Ra and his henchmen convince the Egpytians they’re gods because they possess technology they don’t understand. Emmerich instructed visual effects guru Jeffrey Okun to design the alien technology as much more advanced than Earth’s yet appear like it hadn’t evolved in a long time.

At this point in his career, Emmerich believed practical effects and miniatures were better than CG, but the effects crew convinced him otherwise. Digital effects firm Kleiser-Walczak landed its first major film contract with Stargate. They specialized in Egyptian-style effects for theme rides at Las Vegas’s Luxor Hotel and Casino. They combined digital effects with real footage to flesh out crowd sequences while providing realistic animation to enhance the sets and actors. Their costs were minimized by only hiring the personnel and equipment necessary. The pyramid was digitally placed using plate photography of a five-foot model crafted by Greg Jein. Originally, the alien planet was to have three suns, but the effects technicians couldn’t make it work and proposed three moons instead. The moons were digitally altered pictures of Earth’s moon from odd angles.

Patrick Tatopoulos provided the Egyptian God designs. The script described Ra as an elderly human man, a la John Gielgud. However, when one of Tatopoulos’s concept drawings depicted Ra as a young, androgynous pharaoh, Emmerich felt it was a fresher approach and reconceived Ra as younger. During brainstorming sessions, Mario Kassar suggested Jaye Davidson, whose groundbreaking Oscar nomination for The Crying Game could help sell Stargate to foreign markets. Emmerich and Devlin liked Davidson’s aura of ‘specialness’, of ‘other worldliness’. They were concerned he lacked the acting training to carry a major villain role reciting non-English dialogue but deferred to Kassar’s knowledge of foreign distribution to make an offer.

Davidson quit acting to concentrate on his modeling career. He despised the attention his gender-bending breakthrough performance brought. He only appeared at the Oscars because the film company paid him extravagantly to attend. Hollywood didn’t know what to do with him, seemingly only offering demeaning roles playing freakish characters, something he wanted no part to perpetuate. He wouldn’t secure an agent, fearing he’d take an offer purely for money that made him miserable. When offered the Stargate role, Davidson said he’d only accept if they paid him enough to never need to act again – a million dollars. They paid the million.

After location scouting in Morocco and Mexico, they opted to set production in the Arizona desert around Yuma because everything they needed was within a mile radius of their base. Though the July shoot avoided dune buggy season, the 120-degree heat proved grueling, requiring 60,000 gallons of water and thousands of soft drinks daily for all of the cast, crew, and extras. Production assistants carried water jugs with hoses to spray extras down between takes. Many extras didn’t return; over 16,000 different people played extras over the shoot’s span, mainly Spanish speakers requiring interpreters. Clever effects and lifesize dummies enhanced crowds to look like three times that amount.

The heat forced set construction to be done at night or early morning. The town of Nagada on the planet Abydos, not referred to by name in the film, was only partially built. Only the center of town was constructed while outer buildings were computer-rendered from photographs. They digitally added people walking on bridges, through doors, or opening windows. Originally, the stargate was black but it looked like a giant tire, so they gave it a silver/metallic look. Night shoots were also common, using massive lights to simulate daylight. It took a thirty-person team to sweep away foot and tire prints in the sand before each shot. The massive set structures, reportedly the largest since Cecil B. Demille’s Cleopatra, were too large for traditional studio soundstages, so they rented the domed former Spruce Goose hangar in Long Beach, California, one of the world’s largest at 65,000 square feet.

The alien beasts of burden known as Mastadges were partially animatronic, but also a Clydesdale horse in disguise when appearing alongside live actors that needed to be hosed down constantly to keep cool and an Australian shepherd dog for long-distance solo shots. The bird-of-prey look of the gliders was a last-minute design change to the original look that suggested chariots. They were inspired by a winged scarab belt piece prototype designed by Tatopoulos for Ra, but turned sideways.

Davidson ruffled feathers by persistently expressing his hatred of being there, feeling everyone was staring at him, while his drug and alcohol abuse created behavioral problems on and off the set. Davidson would frequently freeze because he couldn’t remember the Egyptian dialogue. Having Tyson-Smith feeding lines into an earpiece only frustrated him. Next, Tyson-Smith would recite lines aloud while Davidson wrote them phonetically on giant cue cards, but he’d often lose his place or deliver them robotically. Davidson found the Ra helmet heavy, requiring another body double. Davidson also refused to remove his newly installed nipple rings for fear the piercings would heal over; they designed Davidson to wear a breastplate or used a body double.

It wasn’t until postproduction that they secured U.S. distribution, which became critical because the budget expanded to $55 million. Emmerich sent 19 minutes of raw footage without special effects or dialogue to MGM/UA, who had no upcoming movies in their schedule for the near term. MGM liked what they saw enough to pick up the North American distribution rights for a late October release. They covered additional costs with hundreds of tie-in merchandising deals. Because MGM wasn’t sure how to market it, Emmerich and Devlin tried a grassroots approach to find their audience, including attending sci-fi conventions and creating an official website, reportedly the first for a film.

Stargate catapulted composer David Arnold’s career. Arnold was hired because Emmerich loved his work on The Young Americans. Arnold nearly quit composing for films because he’d made no money from his work. He’d just applied for a job as a video rental clerk when Emmerich called. Arnold was given complete freedom to score his way from an outline by denoting how each scene should feel emotionally. Arnold visited the set to meet the actors and gained character insights for finding the right tone. Emmerich adored the score, hiring Arnold for his three next films, Independence Day, Godzilla, and The Patriot.

Kassar felt that Emmerich’s rough cut took too long to get into the action, requesting the removal of introductory character moments like Ra’s abduction and O’Neil’s suicidal remorse over his son’s death from playing with his gun. Unfortunately, test audiences graded this cut with only 40% positive response, claiming the story was slow and hard to follow, especially lengthy sequences involving unsubtitled Ancient Egyptian dialogue. Kassar wanted a further reduction of talky scenes and to add an additional action sequence. Ironically, test audiences deemed this cut with worse scores for slowness. Emmerich and Devlin surmised that the problem wasn’t that it needed more action, but that it needed to invest viewers more into the characters and their mission from the outset.

At this point, everyone expected Stargate‘s failure. Both Carolco and Canal Plus were already facing bankruptcy and a bomb would seal their fate. Carolco especially needed resources to fund the $100 million-budgeted Cutthroat Island. They hedged their bets by selling Stargate‘s franchise rights to MGM for $5 million.

Devlin and Emmerich decided that if everyone else was abandoning it, they’d reinstate the excised expository scenes, plus additional moments not in their first cut so at least they’d be pleased. Test scores improved but they still had a major problem. Audiences despised Ra’s character and Davidson’s performance. Davidson seemed annoying and petulant more so than intimidating or frightening and his attempt at speaking in the pseudo-Egyptian dialect felt unconvincing. The ending was unsatisfying because Ra was merely a pawn of evil aliens, so his destruction did nothing to make the Egyptians truly free. Emmerich and Devlin considered whether they should edit out Davidson as much as possible or request costly reshoots with another actor.

Emmerich had an epiphany. Ra wasn’t a human working for aliens, but he was an alien himself, the last of his kind. They could alter Davidson’s voice and add a sinister glow to his eyes to make him menacing. They’d show his true alien form at the beginning and end to give audiences satisfaction when Ra’s ship explodes that the threat was over. After informing Davidson about these changes, he expressed gratitude. He was in rehab and grateful they weren’t removing him from the movie. With these changes, soared substantially with test audiences.

Stargate grossed $71 million in North America and another $125 million in international markets for a worldwide total of $196 million. It broke the record for the best opening for a film released in October. Spader cheekily instructed audiences to leave their brain at the door, suggesting no brain cells would be burned watching Stargate except for people deliberately trying to figure out the plot.

Stargate is a conceptually intriguing but narratively flawed action/adventure film/ Its strengths stem from the fascinating borrowed ideas of ancient civilization derived from alien influence and the gods were more technologically advanced extraterrestrial beings. Great visuals and visual razzle-dazzle are complemented by a gorgeous score. These efforts are muted by comic book-style writing, with hokey one-dimensional characters and a clichéd plot. Russell is terrific in a subtle performance as the Colonel, but Spader is miscast playing the world’s klutziest professor. Both brilliant and moronic, both impressive and disappointing, credit screenwriters Emmerich and Devlin for having wonderful ideas undercut by time-worn movie cliches. It’s ultimately entertaining but needed a better script to truly soar.

- MGM decided against a cinematic sequel and spun the concept into several television series. Emmerich and Devlin offered to help but MGM said they preferred people with TV experience. MGM also licensed Stargate video games, comic books, novels, and web series.

- Emmerich and Devlin felt Stargate had trilogy ideas. Their second film would feature Daniel Jackson finding another stargate within Mayan ruins and the third would incorporate popular myths like Bigfoot and the Yeti. However, MGM declined further films, feeling they would compromise the TV series’ success.

- In 2013, Emmerich and Devlin approached MGM again to reboot Stargate into a new film trilogy. A deal was struck, with James A. Woods and Nicholas Wright, the same writers working on a sequel to Independence Day, scripting the first draft. However, due to their demoralizing experience on Independence Day: Resurgence, they opted to forgo more studio battles and walked away.

Qwipster’s rating: B-

MPAA Rated: PG-13 for sci-fi action violence

Running time: 121 min.

Cast: Kurt Russell, James Spader, Mili Avital, Alexis Cruz, John Diehl

Director: Roland Emmerich

Screenplay: Dean Devlin, Roland Emmerich