Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)

John Carpenter began writing a number of script treatments just out of film school, some of which would be turned into movies. Prior to his breakthrough with Halloween, Eyes originally came to producer Jack H. Harris, who had bought the rights to Carpenter’s first film, Dark Star, with the ten-page treatment set where a woman working as a photographer of no particular renown in Hollywood finds she has the ability to see through the eyes of a serial killer, a psychotic vagrant she doesn’t know. She eventually contacts a detective to track down the killer, but the killer soon becomes aware of her following him and goes after her. The climax has the woman seeing herself being attacked.

Harris thought they made Dunaway too glamorous and not as vulnerable as she should have been. It was too glossy and chic to have the heart of the original script. Purchased by Jon Peters from Columbia Pictures as a starring vehicle for his then-girlfriend Barbra Streisand as part of his three-picture deal with them. For $20,000, Carpenter was hired to provide revisions to accentuate Streisand’s strengths and to direct. This would give him the money to partially fund his 1976 film, Assault on Precinct 13. Due to Streisand’s accent and the desire to see her in a variety of fancy outfits, the setting was changed to New York City and the photographer one of the most famous sensations working in the fashion industry. Carpenter was not someone familiar with the ways of Manhattanites, so he turned to read Neil Simon to try to catch the personality types and lingo. However, it didn’t read very well, so Carpenter was asked to make some major revisions, including the main protagonist having some sort of romantic relationship with the killer rather than a stranger. Carpenter felt that audiences found the unknown much scarier than the known and despised this idea because he wanted the killer to remain faceless to the audience.

Carpenter was in effect let go when Peters decided he’d need other writers to change the nature of Laura Mars to be more provocative and the dialogue to spark more eroticism and glamour and was eventually replaced for someone who would do things the way Peters and the studio wanted. Carpenter said he’d never want to work with Peters again because of his massive insecurity and inability to take criticism. Peters would rather point out what he thought wouldn’t work in others but no one was allowed to point out problems with his ideas. Peters says that since it’s his money on the line, he’d rather do things his way than to be loved.

Peters first choice of director was Roman Polanski but he was resolutely in exile from charges of intercourse with a minor. Peters moved on to Michael Mille (who had just directed Tommy Lee Jones in Jackson County Jail), who was quickly fired in favor of another director who initially turned it down for being about nothing, Irvin Kirshner, who directed Barbra Streisand in Up in the Sandbox. Kirshner came back around after giving it some thought and realizing a way he could make it about more than a gimmick. Ultimately, Streisand turned down doing the movie because she disliked the weird, erotic turns the film was taking and disliked scary thrillers.

In Carpenter’s script, the protagonist would have vertigo and fall down immediately when seeing the “vision” of someone else’s eyes.

Originally titled Eyes, but changed to The Eyes of Laura Mars by Jon Peters after principal filming wrapped, then dropping the The sometime later. Produced by former hairstylist Jon Peters, his first solo venture as part of his newly signed three-picture deal with Columbia Pictures, while making A Star is Born as a vehicle for his girlfriend Barbra Streisand. Filmmaker John Carpenter had given Peters an eight-page story outline. Peters determined it should be held in the fashion industry because of his years eighteen years of experience in that realm. Originally budgeted at $3 million, it ended up costing $8 million.

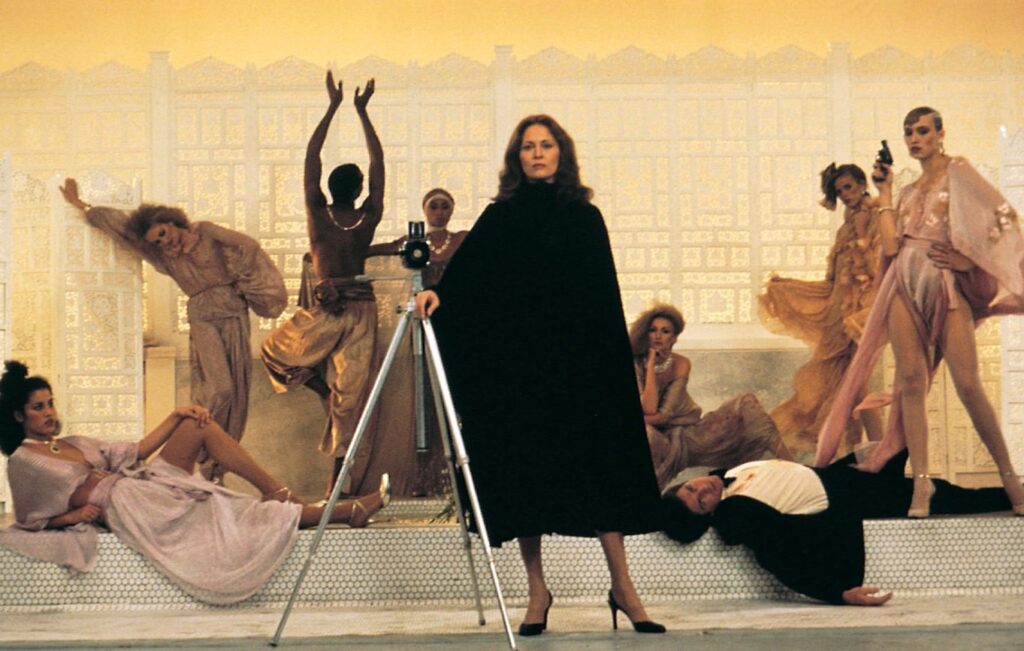

Peters also wanted to increase the erotic nature of the movie by centering the plot around racy and provocative photographs, similar to the sadomasochistic ones captured by Helmut Newton in his book, “White Women”. Newton provides many of the actual photographs used in the film, along with Rebecca Blake. Blake contends that all but two of the photographs used in the gallery sequence are hers and pursued legal action for the misrepresentation and personal and professional embarrassment. Executive producer Jack Harris stated that they were legally required to give Newton the credit for the gallery photographs. The lawsuit was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount and a public acknowledgment that she wasn’t accurately credited.

Since they fleshed out the original outline into a screenplay in 1976, Carpenter and Peters worked on four drafts additional revisions, all specifically with Streisand in mind. However, there were problems with the script that they couldn’t overcome involving how to explain what’s going on through dialogue and needed outside help. Peters enlisted the services of Michael Miller to revise the screenplay and direct, but he soon left after creative differences. Peters continued revising the screenplay with others (reportedly, there were nine total writers after Carpenter who worked on the script at one point or another), including Mart Crowley, Joan Tewkesbury, and David Zelag Goodman, who was limited to writing no more than one page a day while recovering from a heart attack in his long Island home, eventually became too expensive to travel to his house and frustrating, so Kershner brought in playwright Julian Barry, who wrote “Lenny”, to do last-minute punchup. Barry considered the story absurd and suggested cutting out the visions, which enraged Peters, but cooler heads eventually prevailed and Barry was hired. Barry was hired just before and during the shoot, working closely with Associat Producer Laura Ziskin – very closely – they married shortly afterward. Goodman received a co-screenwriter credit with Carpenter.

The final budget was $7 million, with $1 million going to Faye Dunaway’s salary alone. Dunaway had her choice of leading men, although none would be a box office star at the time because the film was built as a starring vehicle for Dunaway. Dunaway was nervous about taking the role, as she had to lose forty lbs. prior to the shoot and she was also struggling in her marriage to Peter Wolf, which made her feel vulnerable and emotional. Peters used his skills working as a hairdresser to talk about the emotional issues with Dunaway as well as to make her look fantastic and feel confident. Directed by Irvin Kirshner, known for making quality films that fell short of financial success – until he directed The Empire Strikes Back two years later. The first film for Faye Dunaway after winning an Oscar for Network. It’s a mystery-thriller that becomes a love story. There is a commentary about the medium of movies. Shot on location in New York City. The set was closed to the press to avoid giving away any secrets. Even the reveals late into the story were withheld from the author writing the novelization while it was being filmed.

Real-life fashion models Darlanne Fluegel and Lisa Taylor make their film debut. It would also be the debut of NY celeb Bill Boggs.

Kershner’s style is reminiscent of Brian De Palma with its use of fashion and photography to fetishize female sexuality as a trigger for violence.

Laura doesn’t have to see the layout to know what to do. She trusts her instincts and not her eyes like the male who is purchasing the photos does, who wants to make sure to have lace, who is told to watch her as she works. The models don’t enjoy the violence; one scene has models pulling each others hair and one gets mad because the other is pulling too hard.

Stabbing of the eyes. Women don’t get to see. Initially, Laura instructs the make-up artists to accentuate the eyes of the models to make them pop, but after the killer makes eyes literally pop out, Laura wants eyes to be softer, and to cover over the eyes with the hair. Women aren’t the ones who use their eyes, but by being too alluring, they may even lose their sight permanently.

“I think what Laura is saying with the

work is, ‘Okay America! Okay world!

You are violent! You are pushing all this

murder on us. So here it comes, right

back at you. And we’ll use murder to sell

deodorant, so that you just get bored

with murder.’”

But is it making people uninterested or is it desensitizing people?

Will Laura Mars still be a successful photographer now that the person responsible for her violent visions are no longer there to provide them?

The shoot was clouded with secrecy. As the film is a mystery, they naturally didn’t want to give away too many hints. Also, Peters was concerned that if too much about the plot leaked out, some television network would make a knockoff made-for-TV version that would deflate interest in seeing the same premise in the theater. In post-production, only the projectionist and editor Michael Kahn were allowed in the editing room.

The release date was moved up from its intended September release to July before finally settling on August 2. Peters followed his formula of promotion from A Star is Born by releasing a book adaptation, a soundtrack (with Streisand’s “Prisoner” released early as a single), and heavily promoting the film with radio spots.

Very good use of locale work around the bustling streets of New York City, many run-down areas that contrast with the elegance of the fashion shoot. The bleakness of the outside world contrasts nicely with the more lush interiors that further suggest the danger of society lurks all about, though the characters might feel sheltered in their comfortable existence.

Killer’s mother was a prostitute whose throat was slit by a man (presumably his father) in front of his young eyes. As the blood dried it became the color of Laura’s hair. There the boy learned that overt female sexuality with a negative stigma leading to violence and death. He can’t stand his own reflection, and stabs himself metaphorically in one eye with the ice pick – one half of himself. Killer accuses laura of being a frustrated voyeur, to which she compares herself to Grandma Moses, someone who started her career later in life. After the first murder Laura says she isn’t going to be able to shoot, but Elaine (her friend in an affair with Laura’s ex) tells her she has to shoot because life must go on.

Laura says her work is an account of the times she is living in. There are all kinds of murder: physical, moral, spiritual, and emotional. The killer says that is a very moral point of view. She can’t stop the murder, but she can show it and make people look at it, just as she is made to look at the murder she can’t stop done by the killer. Laura has been seeing images of murders for two years; she recreates them into her photos.

The set was closed to the press. Dunaway actually studied photography, including lenses and camera equipment for the role.

Dunaway was forty pounds overweight when she signed on for the film. She was forced to lose wight with only a few weeks to go before principal photography began. Dunaway and Peters dd not get along, especially since the screenplay was still not finished as they were shooting, forcing her to invent her own dialogue.

Peters praised Kirchner publicly, but in private, he was dissatisfied with what he considered weak direction.

EYes are stabbed because they are what gazes upon the objects of desire and trigger the conflicted feelings.

In Carpenter’s original screenplay, the heroine doesn’t know the killer. Some of his ideas ended up in his 1978 TV movie, Someone’s Watching Me, where he met future wife Adrienne Barbeau. The only thing remaining from Eyes was the fashion photographer who could see through the eyes of someone else, but that was all that remained.

Both the killer and photographer deem themselves to be doing what they do for moral reasons.

The men in the film are presented as ineffectual of a mature romance with a woman, either gay, ex-cons, gold diggers, or with severe attitude problems, blaming others for their calamities.

Eyes of Laura Mars had been originally planned as a vehicle for Barbra Streisand, who later ended up passing on it, although she did later record vocals for “Prisoner,” the theme song (the only one Streisand has ever done for a movie she wasn’t in). Peters then pursued Faye Dunaway for the lead. Once secured, he hired Irvin Kershner, who Streisand recommended after working with him for Up the Sandbox.. Peters says he never overrode any decision that Kershner was passionate about.

All things considered, it’s hard to imagine someone doing a more superb job than Faye Dunaway here, in another role of a woman with a mysterious story. That mystery is what attracted her to the role, wondering where the mystery might take her from an acting standpoint. Dunaway evokes genuine-looking fright and a disconnect with the people around her that is crucial to give the essence of her sheltered, pampered existence of this woman who is walking a fine line between reserved, old-fashioned tendencies in her personal life with modern-day sensuality. Pre-stardom Tommy Lee Jones shows early signs here of the superb character actor he’d eventually become, displaying strength and gentleness in equal measure, something Dunaway also taps into for Laura Mars, which would be the type of character he’d play in almost every successful role since.

Dunaway stars as chic and controversial Soho-based fashion photographer Laura Mars, whose studio is based in an abandoned Hudson River passenger terminal. Originally from Detroit, Mars has been creating a huge buzz in the entertainment news with her brand of stylized violent imagery used in the photographs she takes, which are readily used in advertising products. She becomes the poster child for all things violent and reprehensible in fashion photography, which draws her plenty of attention, but much of it negative, until she becomes the target of violent behavior herself. Critics and reporters hound her wherever she goes, but even more disturbing is the fact that Laura thinks she has had the vision of the murder of one of her models, and that she witnessed the deed through the eyes of the killer, who stalks his prey with an ice pick. Lo and behold, the woman of her vision has been killed for real, and the similarity of the murder and one of the pictures with the same woman in one of her photography books sends sales skyrocketing. Soon she experiences more of her frightening premonitions, and she reports the incident to the police, but most give her an incredulous look. The only helpful hand comes in the form of hunky detective John Neville (Tommy Lee Jones) who also finds himself getting too close to the woman he is sworn to protect, although Laura doesn’t seem to mind. With more models out there for the killer, can Laura and John get to the killer before he commits any more murders?

Helmut Newton and Rebecca Blake took the photos for the Laura Mars character of the film, portraying beautiful, wealthy, and fashionable people whose lives are disrupted by the violence of the world around them. The seed of inspiration came from the many assassinations that took place among the beautiful and powerful people in the 1960s and 1970s, fostering the notion that no one is safe. Their beauty and opulent lifestyles not only won’t save them but make them targets. The well-to-do continue to try to escape the ills and ugliness of the world by surrounding themselves with beauty, but Laura Mars shows through her artistic photographs the intrusion of that violence and depravity forcing itself into the sheltered lives of the wealthy and beautiful.

Laura Mars is particularly vulnerable because she is open and alone, except for men surrounding her that might be toxic or harmful. The script was still in an incomplete phase when they began to roll film. Dunaway was nervous about working again with something that wasn’t fully formed, but the ideas were sound, and the makers of the film seemed like they were pushing to go places that were fresh and new. Dunaway changed much about the nature of the Laura Mars character during the shoot, making her quite different than what was on the written page, especially in her dialogue.

Tommy Lee Jones was sought by Peters due to his strong presence in “Jackson County Jail,” as well as his ability to handle the sensitive aspects of the portrayal. He didn’t audition but came highly recommended and was very intelligent, strong, and truthful – what was needed for the role.

Laura tells Neville to look through the camera – what you’re seeing through the lens is what the killer sees. When Neville sees himself on the camera, he asks if that’s really what he looks like (he looks like a cop). Laura swings the camera around to capture him more and he waves his hand to hide his face and tells her to stop because it makes him nervous. Neville tells her that the killer could be jealous or thinks that Laura’s work is promoting pornography and decadence and feels it’s his mission to clean up the world.

Raul Julia was a last-minute casting who happened to walk in at the right place at the right time in the lobby where they were shooting. Kershner had seen him in a production of “The Cherry Orchard” and thought him a brilliant actor and talked him into taking the role.

Good stylish camerawork by Victor J. Kemper.

Laura tells Neville that he has her so well protected that she’s like a prisoner in her own house. “Prisoner” is the name of the theme song sung by Barbra Streisand. Neville gives her a gun and tells her to use it if she has to; she’d be doing the don of a bitch a favor.

Kershner was offered the director’s chair a year before accepting. He first turned it down for its weak story that relied on shock value and a trick ending, that had lack of cultural relevancy in Carpenter’s script. He figured out a way to do it and accepted later. By then Dunaway was the star. Kershner wanted the photographs to reflect the violence that was fashionable in professional photography of the era. He found the violence a metaphor, images of violence representing beauty, and images of beauty representing violence. Women try to model themselves after the models in the magazines, which does harm to women. It also harms men, who have the thought planted in their mind that this is the woman that is ideal, a fantasy that can’t be obtained because even the models don’t appear as they do in the magazines.

Men view, women sense the act of being viewed. Laura sees herself through the eyes of the viewer, as an object of both desire and hatred, and it frightens her.

Theme: the scary notion of fetishized views of women in violent situations through the eyes of predatory men. Lust, desire, jealousy, and murder for that which one cannot possess. Examines in particular how women are represented in film and the societal repercussions such representations may inspire. Does pornography and depictions of violence cause more of it, or is it a reflection of societal repression? Sometimes the women are victims and others the perpetrators. They aren’t women but symbols of male desire, fear, and frustration. They’re either threats to men, or are too much of a sexy lure and deserve to be punished. Her sight is the notion that she sees from a male-gaze perspective. There is a connection between Laura’s photography and the actions of the killer, a killer who is objecting to the exploitation on display in Laura’s advertisements, but whose actions are exploited by Laura in continued photography. Her fashion shoots closely mirror those of the crime scenes.

The end of the film requires her to shoot the killer, not with a camera, but with the gun that the killer has provided.

Tommy Lee Jones wrote the scene where he reveals himself to be the killer.

Laura’s occupation is to shoot women with the object of satisfying the gaze of men.

The cop and Laura begin to feel for one another. She grows to depend on him and he finds attraction in her vulnerability in a town that has grown to be apathetic.

Laura’s apartment is full of mirrors, suggesting she likes viewing herself, yet is terrified when she sees herself through the eyes of the killer. The name Mars evokes the Roman god of war and violence, a particular symbol of masculinity. In the media it’s reported that Mars’s work is offensive to women.

Peters says that the phenomenon Laura Mars experiences is real and called telekinesis, with a mix of clairvoyance. He had reporter Geraldo Rivera do some research up in San Francisco for a documentary, but Peters has decided not to release it because it wasn’t something that could be proven, but he thinks audiences will accept it within the film even if they don’t buy it as something that might actually happen.

Carpenter said it was difficult for him to see someone take his words and make them their own, but he was lured in by making big money. He was shocked by how violent and weird they made his story over the three years since he conceived it. He says he felt a bit battered by the end of the process but it was a good learning experience, and it was the reason why he asserted full creative control on his next project, Halloween.

Red herrings abound, but none you buy for even a second, so savvy genre fanatics should have no trouble quickly weeding down the suspects to the culprit. Eyes of Laura Mars was written by famed director John Carpenter after sparking critical interest with Dark Star and Assault on Precinct 13, although David Z. Goodman would come in later to try to spruce it up by changing the identity of the killer. Irvin Kershner directs in a competent fashion, with good use of the camera and sound to evoke some genuine scares as we see the horror in the eyes of the victims as if they were through the eyes of the killer. There is a chic look to the entire production, perfectly in step with the glitzy days of disco that were popular at the time of the making of this film, but the music selection, for what it is, is top-notch.

The film eventually collapses under the weight of its own wafer-thin characters and their inane and sometimes nonsensical actions, especially as it ramps up to its utterly awful climax. The quality actors do what they can to breathe emotion into their roles, but the dialogue does them no favors and they come across as artificial.

Despite the strong performances, pleasing aesthetics, and the occasional scare, Eyes of Laura Mars never evolves to become anything more than a slick, gimmicky thriller, titillating for the moment, but forgotten soon after. Perhaps if the film had started out centered on the character of the killer, instead of Laura Mars, there would have been at least some freshness, and it would also have made the ending seem far less preposterous. The ending is so genuinely terrible that it likely will even turn off anyone that had been riveted by the film all the way leading up to the reveal. Riveting to a point, until the silliness quotient finally sinks it. For Dunaway fans and thriller junkies only.

After being behind one form of a camera as an actor, Dunaway determined that she’d also like to be behind the film camera as a director.

Qwipster’s rating: C

MPAA Rated: R for nudity, strong violence, and language

Running time: 104 min.

Cast: Faye Dunaway, Tommy Lee Jones, Rene Auberjonois, Brad Dourif, Raul Julia, Frank Adonis, Lisa Taylor, Darlanne Fluegel, Rose Gregorio, Meg Mundy

Director: Irvin Kershner

Screenplay: John Carpenter, David Zelag Goodman