3:10 to Yuma (2007)

2007’s version of 3:10 to Yuma is the right way to remake a classic film. Instead of a complete rehash with saltier material, or something so divergent as to be unrecognizable, the screenplay by Michael Brand and Derek Haas (who’ve previously collaborated on some not-so-impressive efforts like retools Halsted Welles’ original work, remaining mostly faithful with its substantial parts, while fixing a few of the weakness that kept a good Western from being a great one. At least one very proactive one replaces the whiny kids. The dumb sidekick is replaced by a posse of men respectable and flawed, but all interesting. The ending of the film, which is perhaps the most significant criticism of the Delmer Daves version, has completely changed. Although not everyone will like the change, there probably won’t be any argument that the final 20 minutes are about as riveting and disturbing as there’s been in the genre in many a year.

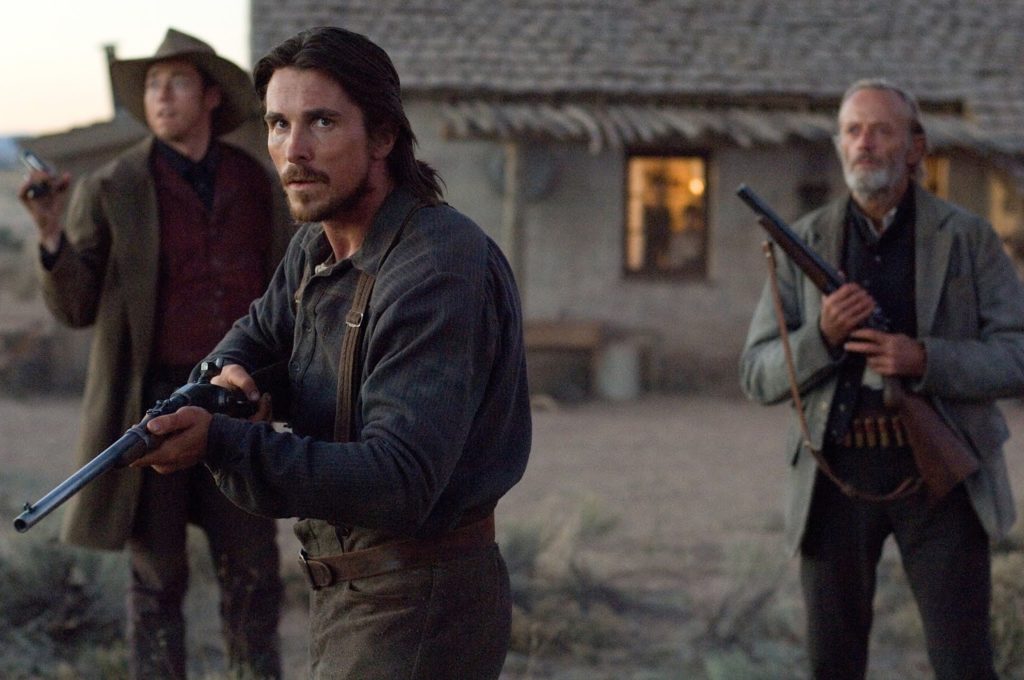

Christian Bale plays Dan Evans, a war amputee that has all but lost his ranch to a wealthy landowner when he can’t grow much in crops for a lengthy period. He needs cash to pay the man off, but no money’s coming in. He gets a chance to earn $200 for escorting a notorious outlaw, Ben Wade (Crowe), from his town to catch the train to Yuma prison, where Wade is sure to be hanged. Wade is a crafty one, and deadly. With Wade’s men out to get him free at any cost, it’s a dangerous quest to get Wade to his destination, to begin with, and even more to get him on the train in time.

The original 3:10 to Yuma was ahead of its time, with its psychological underpinnings and more serious themes than most oaters of its era. Most of today’s westerns, what few there are, are of this sophisticated tradition, so this remake isn’t so much revolutionary as evolutionary. It’s not a Western going for gritty realism by any means, as director Mangold sees many scenes from an action-oriented perspective, but he does set the tone for this early enough that it stays consistent. The actors are a real strength, with Bale doing an excellent job in showing Evans to be a plain man with an unremarkable life, so very disappointing to his son (Lerman) that thirsts for men of adventure. By contrast, Crowe plays his role appropriately charismatic, although toned down in charm from Ford’s original performance, making him much more menacing and compulsive.

One of the exciting things about the film is the handling of the supporting characters, all of whom enhance the movie. To contrast Evans, his posse contains a veterinarian (Tudyk) who is purely good, and perhaps more timid, but willing to do what it takes to feel like he’s become a hero finally. Peter Fonda plays McElroy, a man who claims to be moral and just, but executes his manner of justice in ways that a man like Ben Wade find more reprehensible than anything he does — McElroy willingly kills people who don’t deserve killing while Wade does what he can not to unless necessary. In contrast to Wade, the second in command in his band of outlaws is Charlie Prince (Foster), a much more dark force that helps to contrast Wade as an outlaw by choice rather than by design. There isn’t any evident sense of decency to Prince at all, while the Bible-quoting, occasionally compassionate Wade probably turned out bad because he didn’t see or understand what merit there is in being good.

One of the notable themes to change probably reflects the changes that have occurred in the value system of American in the 50 years that have passed between both films. In the original, Evans did what he did in spite of being given a reason not to because it was the moral and right thing to do. The Evans of today is much more complicated than that, weighing all options, but deciding to continue because of a need to prove self-worth. It’s not a conviction of morals so much as a conviction of not wanting to feel like half a man anymore, financially, physically, and in the eyes of his family. A man doesn’t perform his duties because of a shallow belief in a value system — he does it because it’s what makes a man be a man. In this way, 3:10 loses some of its higher aspirations, but it does become a bit easier to grasp from a motivation standpoint. He doesn’t act out of a sense of goodness o much as a desire to aspire to greatness.

I think the same can be said about the movie. It’s not a moral values lesson so much as a genre exploration that blends traditional and revisionist Western techniques, taking the best of both worlds to make something that is both action-packed, thoughtful, and thrilling. Like the spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone, there is quite a bit of style on the surface. Still, underneath, you can see creative wheels turning, questioning the traditional value system that had once been part and parcel of Hollywood Westerns. 3:10 to Yuma is a film that offers much in gray areas, with a good guy who is deeply flawed and a bad guy who isn’t rotten to the core. Like most films that depict two sides of the same coin, the desire to switch places between the men is ever evident, if not for the path they chose that prohibits them from doing so. The end of the film has the men meet halfway, in a manner which is intensely gripping, and eternally beguiling at the same time. If the original’s ending weakens the film, it can be argued that this version’s ending makes it.

Qwipster’s rating: A+

MPAA Rated: R for violence, brief nudity, and some language

Running time: 117 min.

Cast: Christian Bale, Russell Crowe, Logan Lerman, Ben Foster, Dallas Roberts, Peter Fonda, Alan Tudyk, Gretchen Mol, Vinessa Shaw, Luce Rains

Director: James Mangold

Screenplay: Halsted Welles, Michael Brandt, Derek Haas (based on the short story by Elmore Leonard)