After the Storm (2016)

Japanese broken family drama specialist, Hirokazu Koreeda, returns with another delicate gem, After the Storm, which continues his string of modest but telling stories that revolve around how families mold us, but also how our selfish instincts sometimes fail us. Easy-going, slightly offbeat, and willing to engage in the comical side of his characters, while remaining heartfelt in approach, his film is a subtle but rewarding look at three generations of males in the family, specifically in how fathers manage to fail to live up to expectations, mostly because they seem unable to accept and enjoy their existence in the present. It’s a film that runs more on character study more so than a ready-made plot, but with such fine detail that it says so much more to us than a more conventional approach might.

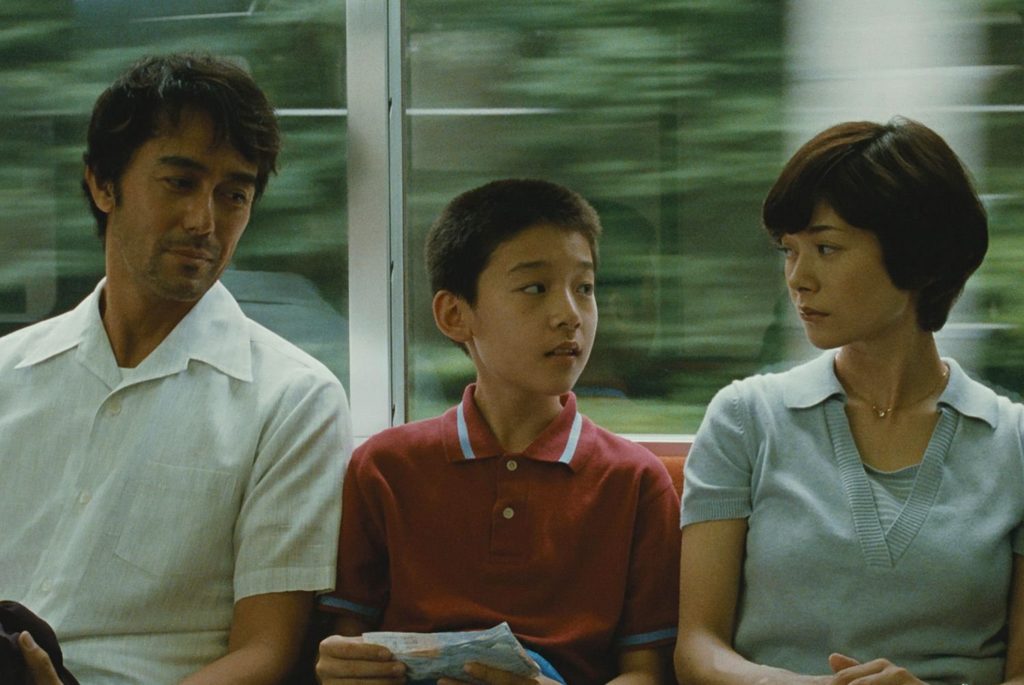

Hiroshi Abe plays Ryota; a struggling author turned two-bit detective (more like blackmailer) who has seemingly squandered his early success through bad decisions like an addiction to gambling and inability to be responsible for himself and his commitments to others. It’s what cost him his marriage to Kyoko (Maki, Infection), and what might cost him his ability to continue to visit his son Shingo (Yoshizawa) regularly in the future. It’s something that doesn’t sit quite well with Ryota, as he fears to become as remote to Shingo as he had been to his own recently deceased father during his childhood. When a typhoon strikes, Ryota finds himself forced for a rarely prolonged stay at his grandmother’s (Kiki) apartment, and a long-in-coming conversation with Kyoko, with whom he still is very much in love, and the hope that they might be able to resolve their differences to become a family again.

The storm of its title, of course, is a metaphor for the destructive force that has caused quite a bit of damage and debris to prevent the lives of this family from getting back on track. However, the film, at least in its English title (the Japanese title translates to “Still deeper than the sea,” which is a lyric from a song contained within the film), is called After the Storm, which is a different connotation. Storms can destroy, but can also cleanse and purify, leaving a clean slate from which to draw upon fresh ideas. It’s a time when one must pick up those pieces of debris and begin to rebuild. It’s also a time when the moisture in the ground combines with the sunlight as the clouds dissipate when new life emerges. There’s hope here for all involved that the new life will produce better days.

There is a tenderness Koreeda brings to his characters, as well as a certain amount of love, that makes After the Storm, which many have claimed to be a spiritual successor to his 2008 gem, Still Walking, a delight to delve into and examine. Very few features so elegantly capture the maturation process from beginning to end, showing how influences mold us, how our behavior sometimes betrays us, and what that causes to our perspective on life once we achieve an age in which we have to settle into the bed we’ve made for ourselves and our families. This is especially true in times of loss, as those left behind pick up the fragmented pieces, while also trying to find ways to cope with filling the voids necessary of those people no longer present.

In addition to the specific relationships, After the Storm also looks at how class comes into play in terms of feelings of contentment. Ryota is barely scraping by, but stuck in such a rut of immaturity and clinging to his past, and he’s having a tough go emerging out of it. Rather than work on himself, he extorts money from adulterers he cases on the job to score a few extra bucks, which he immediately uses to gamble on such things as horse races and the lottery, hoping to turn his meager earnings into a tiny fortune. He’s chagrined to learn his mother has tossed out most of dear old dad’s things, as he would like to hock the merchandise, and finds that his father was also doing the same toward the end of his life. Meanwhile, mother has had a lifetime of feeling like they’ve never progressed, buying their apartment in their youth as a stepping stone to perhaps getting their own home, then remaining their entire lives living in the projects where seemingly young and hopeful people never escape.

Koreeda specifically looks at male weaknesses in relationships. Women can move on, sometimes immediately, such as in the grandmother’s case, who tossed out her husband’s things shortly after his passing, or in Kyoko, who has managed to seek another potential mate, despite Ryota still lingering as if waiting for her to reconsider. Koreeda compares this to an oil painting, where the new man is painted over the old, which is still present in the memory but has no place still existing in sight. Ryota loves her, but she has more needs in a relationship, explaining to him that, “Grown-ups can’t live on love alone,” which both admonishes Ryota for offering nothing else to attract her, as well as to suggest he’s not quite grown up yet, despite being about 50 years old. More explanation from the grandmother, who observes that men don’t appreciate what they have in the present — “I wonder why it is that men can’t love the present. Either they keep chasing whatever it is they’ve lost, or they keep dreaming beyond their reach.”

Ryota’s immaturity becomes a focal point for his main issues, as he appears to be stuck in a state of regression, and returning to his childhood home only exacerbates those feelings. In a critical scene, he returns to his favorite hiding spot, the octopus slide in the park near his mother’s apartment complex. His height is continuously referred to as one of his assets, and yet, he finds his frame also means he isn’t able to look or be treated like a kid again, though he still feels young at heart. Ryota confesses to Shingo that, “It’s not easy growing up to be the man you want to be,” but further compounding Ryota’s issues are the fact that he finds it not so easy to grow up to be a man with responsibilities of any sort, either as a husband or as a father. When Ryota offers to play the board game, The Game of Life, in which a person traverses through most of the life goals we associate with living in modern society, with Kyoko, she declines – it would be a cruel joke for Ryota to achieve so much in a game that he could not sustain in life.

Koreeda has stated that he makes films like this, which contain a few autobiographical elements, as a way to resolve to understand his own family, and in turn, himself. However, as many of the conscious themes of the film are universal, such as how (despite our best efforts) we always seem to take after our parents, it’s an instantly relatable film on many levels to just about any culture in the world, as we can also learn about ourselves and reflect on our own lives, our struggles and our ability to persevere, within the finely detailed course of After the Storm. There’s a persistent push and pull that occurs in the dynamics in the family, at one time seeming to start to unravel through the actions of one person, then a time of healing and closeness through the efforts of another. But, despite differences, there’s a sense of belonging and identity that keeps these relationships intact through whatever storms they must weather.

Qwipster’s rating: A

MPAA Rated: Not rated, but probably PG-13 for mild sexual references and language

Running Time: 117 min.

Cast: Hiroshi Abe, Kirin Kiki, Yoko Maki, Taiyo Yoshizawa

Director: Hirokazu Koreeda

Screenplay: Hirokazu Koreeda