The Last Unicorn (1982)

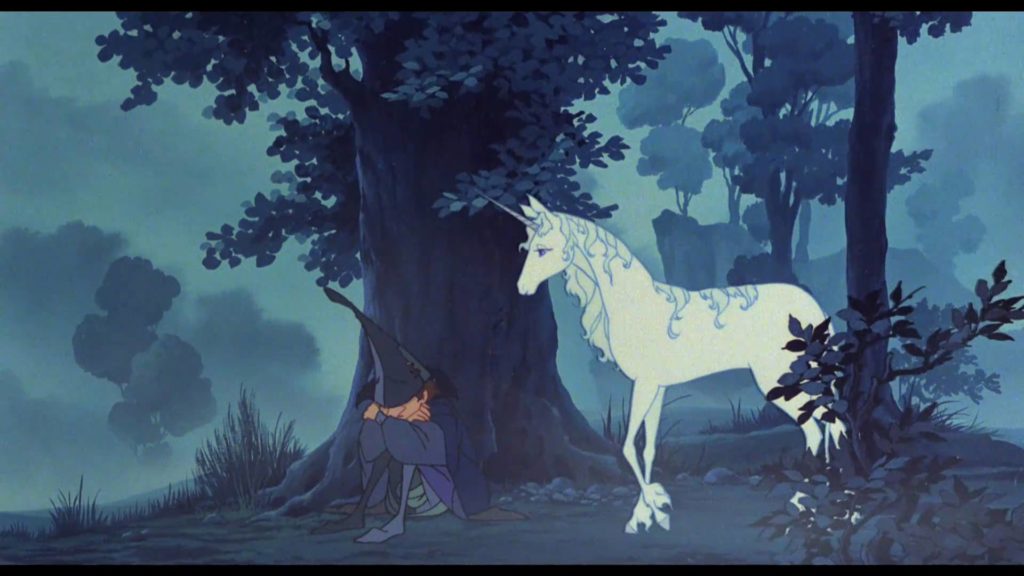

One magical unicorn survives the fate imposed by the wicked King Haggard (Christopher Lee) in his attempt to exterminate the realm. Thinking they couldn’t possibly all be dead (in this story, they are immortal), the unicorn, along with help from an apprentice magician named Schmendrick, sets off from her forest home to find her lost kin.

The Last Unicorn is directed by Jules Bass and Arthur Rankin Jr., who gained notoriety in the animation world for their stop-motion animation work from television on such holiday classics as 1964’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and 1969’s Frosty the Snowman, and, sometime later, the 80s animated TV show, “ThunderCats”. Peter S. Beagle adapts his own novel, originally published in 1968, having done prior screenplay work co-adapting J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” for Ralph Bakshi in 1978, the unrelated animated follow-up to Rankin & Bass’s “The Hobbit” the previous year, which Bass and Rankin directed and produced. Beagle brings a strong sense of characterizations to the various roles, allowing us to observe some flaws within the good people, and some complexity among the ones who are not as kind.

The Last Unicorn isn’t concerned with action sequences so much as exploring the emotional underpinnings of the adventure, with melancholy remembrances and finding the goodness underneath the acts of cruelty that could crush many with dismay without perseverance. Few animated features would delve head-first into anxiety, sorrowfulness, and regret. Even the showdowns with the dreaded and fierce Red Bull, the mammoth supernatural emanation responsible for the demise of the other unicorns, force into the sea beyond King Haggard’s castle, are there more for conflict than to dazzle us with feats of derring-do. It’s a story that explores loss and the resulting loneliness, forgetting oneself when away from one’s roots, as well as the difference between fact and illusion, which is very sophisticated for a vehicle that primarily finds children as its main audience.

For children, it gives a taste of how different the world may be when venturing out from one’s own safe place, their comfort zone, and how we might lose our connection with those things we hold dear if separated for too long. In other words, it’s about having an experience with maturing, beginning to forget the safety of one’s own safe and secure childhood, and new possibilities, both strange and scary. Every child dreams to be a grown-up in theory, but The Last Unicorn suggests that it isn’t always the road to happiness, and giving up the shelter and security one feels is impervious to harm is, indeed, something that can be frightening to ponder from the vantage point of early youth. For adults, we only have vague memories of that life we once had, something the unicorn experiences during a transformation in one sequence into a human woman, as we begin to lose touch with that former life of ease and comfort. We seek to re-capture our youth, embodied in Haggard’s quest to capture the unicorns or become preoccupied with masking becoming old and decrepit with illusion and deception, or in leaving a legacy behind so as not to be ultimately forgotten.

The voice work includes some well-known stars in prominent roles, though it is Farrow that is least intrusive, matching the majestic elegance and innocent grace of her role perfectly. Arkin gives the Schmendrick character a bumbling but well-meaning likeability that benefits the story as well. It’s hard to believe that Jeff Bridges, voicing Haggard’s lovelorn son, Prince Lir, was once less cartoony with his voice than he would eventually become when he started doing character work in his live-action starring vehicles in his later years. The one vocal appearance that’s the most out of place is in casting comedian Robert Klein as The Butterfly; it’s a fairly superfluous role, only there to impart the news that there is now only one unicorn left, though the butterfly begins to sing songs that are anachronistic to the time and era for which one would imagine such an olden tale taking place.

The often beautiful animation stands out for an English-language release, an American film produced largely in Great Britain but with a strong Japanese influence in its style that draws inspiration from the Unicorn Tapestries of the Middle Ages in Europe, with the backgrounds and much of the overall art design has been through collaboration with Topcraft, a studio from Japan that contained many of the talents that would form Studio Ghibli a few years later, to complete. And speaking of America, the folk-rock supergroup of that name sings several songs crafted by legendary songwriter Jimmy Webb, a friend brought on by Jeff Bridges, for the soundtrack, including a couple that is sung by Farrow and Bridges. They are sweet and add to the bittersweet mood of the story, though the soundtrack doesn’t stand out among their most memorable work. While the songs are nice, they are competing for time with a very obtrusive score, again composed by Webb, that either is incongruous to the tone of the scene at hand or coats them with sound at moments where a quiet beat would suffice.

While it may have only been modest at the box office in 1982, given its smaller budget for an animated feature ($4-5 million, reportedly), it probably would have garnered higher attention if it hadn’t been one of many casualties in trying to earn family-film dollars at a time when E.T. the Extraterrestrial was still top of the chart (not to mention, a re-release of The Empire Strikes Back had been slotted for release its opening week). It’s also a bit odd in its story and tone, as it is much different than more mainstream fare produced by Disney and other American studios at the time, and some children even find some of the events and characters within the film as genuinely unsettling in effect. Nevertheless, The Last Unicorn has garnered a loyal following among those who enjoy animation and fantasy films, especially of the 1980s. It’s a gentle and wistful tale that stands up for children to get in touch with inner emotions that other projects lack sufficient writing or studio bravery to engage.

Qwipster’s rating: A

MPAA Rated: G, suitable for all audiences (mild violence)

Running Time: 92 min.

Cast (voices): Mia Farrow, Alan Arkin, Jeff Bridges, Tammy Grimes, Angela Lansbury, Christopher Lee, Keenan Wynn, Paul Frees

Small role (voices): Robert Klein, Rene Auberjonois

Director: Jules Bass, Arthur Rankin Jr.

Screenplay: Peter S. Beagle (based on his novel)