Legend (1985)

Ridley Scott takes the director’s chair for this visually arresting, Victorian-style fairy tale, which he states he made for children like his children with classic Disney animation films in mind. Indeed, one can see and hear evidence of the cartoon-like quality of Legend within the character designs and posturing, evoking the likes of Peter Pan, The Jungle Book, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella and many other fairy tales of the 20th century tradition, including Jean Cocteau’s take on Beauty and the Beast, combined with the Fall of Man story from Genesis, and this is especially evident in the quality and texture of the voice work. There are even a couple of musical interludes.

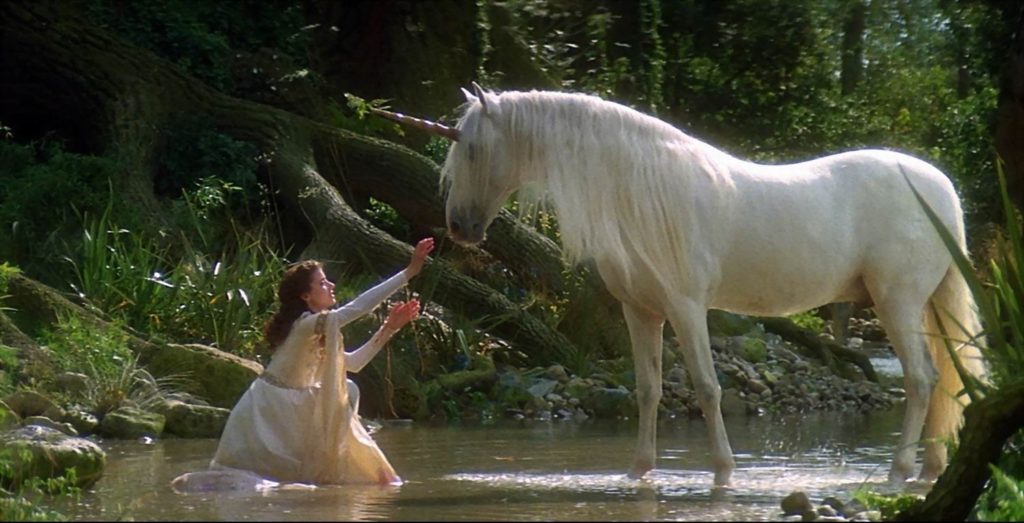

The setting is a mythical place and time common within enchanted tales of fantasy, a pleasantly wooded patch of sun-lit paradise filled with faeries, nymphs, unicorns that communicate like humpback whales, and a pure-of-heart princess named Lili. Paradise turns into a hoary place of cold and bleakness when the demonic Lord of Darkness, who resides in a vast underground cave, unleashes a wicked plot to bring his brand of evil to the surface for all time, hoping to block out the light-giving sun. Mischievous evil minions do much of Darkness’s dirty work, on a mission to stamp out the purest goodness in the land by returning the horns of the unicorns, who are said to be the one thing that keeps pure of heart from becoming enveloped by eternal darkness. It’s up to the brave peasant Jack of the Green, who is smitten by Lili, to save the day, literally, from complete and eternal darkness.

Onboard for the visual effects is Rob Bottin, who came to prominence with his make-up work in John Carpenter’s The Thing, and who would go on to bigger works later in the decade in such films as Innerspace, RoboCop, and Total Recall. Bottin, along with makeup supervisor Peter Robb-King, would go on to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Makeup.

Legend manages to become more interesting when scenery-chewing Tim Curry, under lots of make-up and prosthetics, gets in front of the camera, playing a charismatic and strangely hunky version of Darkness, who is painted deep red, with massive bull’s horns (some will be reminded the Red Bull in another 80s film about the attempt to exterminate the magical unicorns, The Last Unicorn). In contrast with most of the heroes, Darkness has a discernible personality and intelligibility, even if his delivery and deeply altered voice (think Kylo Ren in his helmet in The Force Awakens), invokes a cartoon-like quality.

Those looking back to this film thinking it a Tom Cruise vehicle may be somewhat disappointed, despite ample screen time, as the pre-Top Gun film had been shot prior to his established stardom, and, despite being hot off of Risky Business, doesn’t utilize his own charisma and screen presence in ways most of his later films had been built to foster. He squats throughout most of the film, perhaps to show his self-image regarding his lowly social status, yet is so ostentatious in its pervasiveness to the acting performance that it becomes yet another instance where style creates a distraction from the story. It should be noted that Cruise himself grew disgruntled at the short shrift given to his role in the film, wanting to do more with it than Scott would allow, to the point where, upon release, Cruise did nothing to help promote it, especially as he hated the cuts that were made to the film on top of it. Mia Sara is nicely cast as the fair maiden in her first big role, even if the role seems under-defined, given her level of importance to the overall story. Robert Picardo fans will delight knowing that he plays the most unnerving character in the film, Meg Mucklebones, a slimy and decrepit witch that resides in a murky swamp, even if he is completely unrecognizable under all of the make-up and prosthetics.

Although generally praised for the aforementioned style, the cinematography is coated with perpetual visual noise in every frame, from the motes and pollen floating throughout the forest paradise, to the snowy overlay that somehow doesn’t seem very cold at all, to the sparkly fairy dust, to the floating bubbles, to the glitter-peppered skin, the beaming armor and weaponry, the blizzard of flower petals, to the raging fires of the foundry, there is a concerted effort to always keeps your eyes dazzling with something that’s flickering in the foreground or background. Once you notice it, you won’t be able to stop noticing it, as it comes on so thick, so often, it begins to encroach upon satire. Perhaps that’s the point; when the story isn’t working, why not overload the eyes of the audience with plenty to keep their eyes flitting and mind titillated. It’s hard to believe that the screenplay from novelist William Hjorstsberg, completely based on Ridley Scott’s own story ideas, would have gone through about fifteen script revisions over the course of three years when it feels vastly more underdeveloped when compared to the amount of energy and care that went into the set and costume designs.

Test screenings for audiences in the 1980s saw a considerably edited version of Scott’s vision hit the theaters in 1985, as the powers that be at MCA/Universal Pictures were concerned at the film’s length compared to its story (Scott’s original cut ran just over two hours, then chopped to 113 minutes for test audiences who ended up still not feeling it), and in not putting in a more modern score that would appeal to soundtrack-buying teens, as had been the norm at the time, even for fantasy films. Something closer to the originally intended cut is now available on home video, including the original Jerry Goldsmith score (the US theatrical version replaced his music with the atmospheric synthesized sounds of Tangerine Dream — who composed their version in less than a month, and who had come to prominence for the memorable score to another Tom Cruise film, Risky Business).

To date, there are at least five versions of the film, not counting the original workprint that can be found on bootleg form, floating around — the 89-minute US theatrical release, the previous 94-minute European theatrical cut with a more subdued Goldsmith score, another take released solely for Japanese audiences, one with re-edited scenes specifically for TV showings on Universal’s own channel, and the now most popular go-to, the Director’s Cut), which speaks to the difficulties of the production as wrangling occurred in order to make sure that audiences could be given a release they would enjoy most.

Though generally feeling more like a style-over-substance indulgence, there are some arresting moments within that emphasis on style. Perhaps the most striking is the Faerie Dance between Lili and a faceless sorceress-turned-seductress who matches her dance until the two become one, which, in modern terms, feels very reminiscent of a similar confrontation that occurs at the end of 2018’s Annihilation.

If sumptuous style and eye-popping imagery is something that attracts you to films of fantasy, you’ll likely find more mileage in Legend to find a satisfying experience. It’s all so much costume work, make-up, lighting effects and sparkles, all waiting for a compelling story to inject them into — a story that doesn’t really make you care much about his it resolves, and thus, is a failure as a fairy tale worth relating in any form beyond witnessing the moody imagery on display. The film has garnered a passionate following, but, by and large, most critics still haven’t come around to the film as being anything more than a colorful misfire in Ridley Scott’s early filmography. For me, the problem is that the characters and their plights are not nearly as interesting to observe as what unceasingly diverts the eye.

Qwipster’s rating: C

MPAA Rated: PG for fantasy violence and some scary moments (I’d rate it PG-13)

Running Time: 94 min.

Cast: Tom Cruise, Mia Sara, Tim Curry, David Bennent, Billy Barty, Alice Playten, Cork Hubbert, Peter O’Farrell, Kiran Shah, Annabelle Lanyon, Robert Picardo

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: William Hjortsberg