Wild Style (1983)

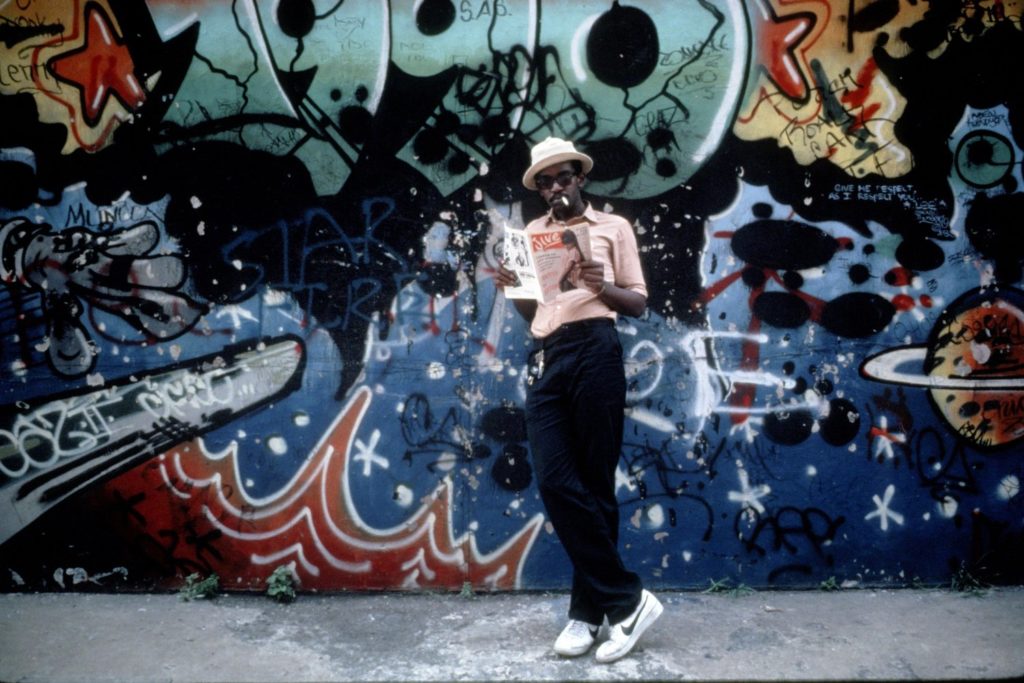

A drama with some documentary-worthy concert performances, Wild Style, which is a slang term for the jittery lettering of graffiti, is a seminal hip-hop film, covering some of the origins of the art form in the home it flourished from, the run-down areas of the South Bronx. In addition to rap music, the film takes a broader look at hip-hop culture, including street graffiti, break dancing, and house parties. Our thread through the story is a Puerto Rican graffiti artist Raymond, under his pseudonym as Zoro, who explores a variety of ways to take his talent and make a living out of it by transferring his skills with spray cans to canvas, culminating in neighborhood wheeler and dealer Phade (Fab 5 Freddy, future star of “Yo! MTV Raps”) securing Zoro’s chance to decorate the main stage at a big hip-hop concert venue in town.

Side stories involving Raymond’s attempt to keep the interest of his fellow tagging lady love Rose (aka Ladybug), as well as Phade giving the tour of the underground scene to a big-time fish-out-of-water New York art columnist (played by indie actress and former New York gallery owner of renown, Patti Astor) looking for her next scoop.

Wild Style is written and directed by Charlie Ahearn, who conceived of the film with collaborator and supporting player Freddy (“Fab 5 Freddy”) Brathwaite, who thought he should make a movie about what’s happening in the local underground art and dance scene rather than another martial arts flick he had been intending (a follow-up to his first feature film, The Deadly Art of Survival). Ahearn cast “Lee” Quinones, someone he met several years before who exposed him to the underground hip-hop scene before it was ever put on wax while making another film, this one his first attempt at a martial arts flick. He later cast non-actors in most of the roles, mostly playing themselves, or some variation, as Lee Quinones, at that time, was a real-life subway graffiti and handball court wall muralist of some renown, known for putting political messages in his pieces. He did transition away from painting subway cars to canvas toward the late 1970s and toured various countries displaying his new art pieces. Sandra “Pink” Fabara, who did have a romance with Quinones, and Andrew “Zephyr” Witten were also graffiti artists in the area, and much of the film was shot in the Bronx neighborhood where they resided.

In some ways, the grainy, 16mm-film stock of Wild Style gets praise among those who’ve studied film due to its vibe of mixing very low budget productions with capturing slices of real life at the time, and, though it did shoot with some attempt at scripting (Ahearn would write each scene the night before shooting), the loose adherence to the written dialogue (the cast laughed at Ahearn’s attempt to sound street, so they adjusted their dialogue to make it authentic) is very reminiscent of the highly improvised works of John Cassavettes and some of the more notable cinema verite examples of European cinema (it may not surprise anyone seeing the film to learn that much of the funding for the $200,000 budget came from German and British investors). Violent crime isn’t a critical part of the story, in contrast to much hip-hop cinema that would emerge in the 1990s. Still, there is one intense scene in which the out-of-place columnist nearly finds herself at gunpoint from a trio of hoods who want something from her before they determine they don’t want her at all. In place of traditional fights among gangs comes the rap battles among rival crews, each taking their turns to either dis or brag as to why their crew is the better of the two.

By the same token, some who are looking for production values and quality acting will likely confuse Wild Style with a bad film, as it is not exactly a treat for the eyes or ears in terms of the cheap film stock and mono sound design, full of non-professional actors who did mostly improvised their scenes which were shot in one take. However, some would also consider it an asset in regard to the film, as it is about those who make next to nothing, creating what some might consider an eyesore, or bad to the ears, or a new form of dance from a beat and a piece of cardboard, and making it for those who know and appreciate the talent it takes to do it well. Think of it like a semi-documentary, with fictional parts that were re-enacted from real things that happened to the characters, and you’ll come to appreciate the film for its authenticity and earnestness in capturing the lives of the underground artists of the street at that time and place.

Though the film itself may have been influential of other films covering the world of rap (Beat Street and Krush Groove offer broader, glossier takes), it’s really the influence on those rappers of the future that Wild Style would emerge as a source for what’s possible, setting the blueprint of hip-hop crews and party rockers for the next several decades. The marriage of hip-hop to street art and break-dancing would also become solidified, and samples of the dialogue and some of the tracks are still incorporated among DJs today. It remains one of the best films ever made about hip-hop and features so much rare footage of rap’s first generation that it is not only a solid film but essential, time-capsule worthy stuff to preserve.

Qwipster’s rating: A-

MPAA Rated: R for sexual references, drug content, and language

Running Time: 82 min.

Cast: ‘Lee’ George Quinones, Lady Pink, Fab 5 Freddy, Patti Astor, Andrew Witten, Busy Bee, Cold Crush Bros., Rock Steady Crew, Fantastic Freaks, Double Trouble

Small role: Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizard Theodore, Grandmaster Caz, Kool Moe Dee

Director: Charlie Ahearn

Screenplay: Charlie Ahearn