The Shining (1980)

Stephen King’s idea for “The Shining” came in 1974, after moving with his wife and toddler son to Boulder, Colorado to explore a new setting to write about. Lacking inspiration, the Kings stayed as the historic Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, entirely vacant the day before winter closure. Its bar was empty save for its bartender, Grady. They dined at the only restaurant table not under plastic and overturned chairs. The tuxedoed band played for an empty dance floor. Returning to their presidential suite, Room 217, King peeled back the shower curtain surrounding the claw-footed tub and imagined a woman lying murdered in it. King felt this was the perfect setting for a horror story in the vein of “The Haunting of Hill House.”

That night, King experienced a nightmare involving the hotel’s fire hose chasing his son down the hallway. He recalled his unfinished story, “Darkshine”, concerning a psychic child whose dreams became reality. As an homage to Ray Bradbury’s “The Veldt,” where children use technology to create a virtual environment that turns real and deadly, King reimagined “Darkshine” as a place, an amusement park that was like a storage battery for negative supernatural energy, feeding off of the psychic child’s power. King abandoned the story, struggling for a plausible way to keep the family trapped.

King reconceived the idea as a Shakespearan tragedy, with the family being hired as caretakers for an empty, isolated Rocky Mountain hotel, the Overlook, during the snowy season. Young Danny Torrance is gifted with ESP, his father Jack is a tempestuous alcoholic, and his mother Wendy is racked with guilt. Jack hopes writing a successful play will rectify his dreary life. The hotel has a history of evil, including Grady, a former caretaker who slaughtered his wife and daughters. The Torrances experience supernatural occurrences, enticed by the ghosts of the Overlook to repeat its evil history. Inspired by John Lennon’s “Instant Karma” (“We all shine on”), King retitled his story, “The Shine,” referencing the boy’s powers.

Around this time across the Atlantic, director Stanley Kubrick grew worried that Barry Lyndon‘s lesser commercial success threatened his substantial filmmaking freedom. He needed a commercial hit. The Exorcist and Jaws were recent smashes, rekindling his long-running desire to make a film so scary that they’d attach a money-back guarantee for anyone watching to the end. Kubrick hunted for ideas, stumbling on Diane Johnson’s 1974 psychological detective novel “The Shadow Knows.” Kubrick admired Johnson’s ability to evoke dread, anxiety, paranoia, and fear. Kubrick began calling Johnson her, conversing at length about politics and books, then flew her to London to discuss collaboration possibilities.

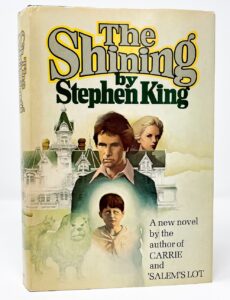

Prior to publication, Producers Circle bought film rights to “The Shine”, then sold it to Warner Bros. Warner production chief John Calley sent a galley proof to Kubrick, who was under a three-picture deal. Kubrick considered it the first worthwhile book Calley sent – an ingenious psychological study of a “family slowly going insane together.” While reading, Kubrick mentally cast Jack Torrance with Jack Nicholson, someone he’d courted to play Napoleon in a never-made passion project. Nicholson, wanting to work with Kubrick, agreed without reading it.

Although the contract required King to provide a screenplay, Kubrick never read it, wanting to go a different direction. Kubrick felt that evil should only exist within humans, not hotels. Whereas King saw ghosts as damned souls, Kubrick viewed them as optimistic proof of existence beyond oblivion. Meanwhile, a Doubleday exec pointed out King’s title was problematic. A “shine” was derogatory slang for a black shoeshiner and his story’s hero, Dick Halloran, is a Black cook. King modified it to “The Shining,” despite it seeming unwieldy.

Kubrick felt the book ending with the blowing up of the hotel was cliche. Rather than Jack sacrificing himself as the hotel’s boiler exploded, Kubrick would have him killed by Wendy in self-defense, while Halloran, who saves the day in the book, would surprise audiences by revealing he is allied with the ghosts and finishes off Wendy and Danny. An epilogue would Ullman giving a new caretaker a tour, ignoring the Torrances as unseen ghosts at the dining table. Kubrick ran the idea by King, who protested. Audiences abhorred seeing characters they cared about dying for a cheap twist and would call for his head on a platter.

Kubrick took King’s advice to heart. In his official first script treatment, laid out the basics for how the film would ultimately play. Exceptions include a flashback sequence of Jack beating a former student at his college out of jealousy that he had a life of privilege he’d always been denied. There were more Indian motifs in Danny’s visions, Grady’s first name was “Daniel”, and, of course, the ending. Kubrick retained the evil Halloran twist, but Wendy and Danny would prevail. The new epilogue would show Jack within a photograph taken at the Overlook’s New Years’ party picture from 1919 in a scrapbook.

To flesh out the screenplay, Kubrick connected again with Johnson, because she taught Gothic Literature at UC Davis, She read King’s book; it was pretentious and predictable, but undeniably scary. She agreed to help, staying in London while frequenting Kubrick’s Hertfordshire estate to develop script concepts. They watched horror movies to spark ideas and avoid cliches. They examined Nicholson’s performances, noting he excelled when his energy was high.

Kubrick wanted to explore the psychological origins of fear. Johnson shared Freud’s 1919 essay on “The Uncanny,” delving into repressed memories as fear triggers. Kubrick observed Kafka’s straightforward approach to fantastical happenings and H.P. Lovecraft for never explaining mysterious elements. They also referenced Bruno Bettelheim’s 1975 work on fairy tales, “The Uses of Enchantment,” and Frank Kermode on “endings,” exploring romanticized dreams and memories. They concluded that the Torrances feared feeling powerless, and audiences found a father murdering his family terrifying.

Dividing King’s book into eight acts, they wrote separately, then merged ideas. They discussed returning to the original notion of Halloran saving the family. Johnson said horror movies should have at least one person killed. She suggested Danny; the end could show a child’s chalk outline, with Danny’s ghost laughing and playing near it with the deceased Grady sisters. Kubrick said that was impossible, possibly due to being tender-hearted and possibly because Danny’s invisible friend Tony was really Danny from the future (in King’s book, Anthony is Danny’s middle name), which meant Danny couldn’t die. They’d continue with King’s ending as a placeholder until something better emerged. Kubrick wrote Jack’s part while Diane wrote Wendy’s.

Kubrick contemplated his first US location shoot since 1960’s Spartacus, but his hatred of flying and desire for secrecy left him opting for London’s EMI-Elstree Studios. Scenic American hotels photographed by production designer Roy Walker inspired massive soundstage recreations, specifically Yosemite’s Ahwahnee for interiors and Mount Hood, Oregon’s Timberline Lodge for exteriors. Montana’s Glacier National Park provided the opening aerial shots. Soundstages weren’t large enough for a full-scale hotel, so they filled space economically, jigsaw-style. The layout might not make geographical sense, but Kubrick surmised ghost stories need not be logical. Photographs and television programs were loaned by Warner Bros. archives to save money.

King’s Wendy was blonde, gorgeous, and independent. Kubrick considered actresses who matched well against Nicholson’s physicality: Lee Remick and Jane Fonda. Wendy should experience repressed sexual dreams, including a masked ball orgy that tied into King’s many allusions to Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death”. Nicholson suggested Jessica Lange as a possibility, someone with whom he could explore Jack’s sexual side and really unnerve audiences. However, Kubrick returned to his treatment notion of Wendy as a common housewife and old-fashioned country girl, someone who’d more likely tolerate Jack’s abuse. Kubrick admired Shelley Duvall in Robert Altman’s films. Her mousy vulnerability, Texas accent, and unconventional appearance made it plausible that Jack would abuse her for not being the kind of woman a man like him deserves. Kubrick removed the orgy and Poe references, opting for Kafka’s rational approach to depicting fantastical events.

For Danny, they advertised for photos of boys aged 5 to 7, no acting experience necessary. The most photogenic candidates were interviewed, testing their memory, responsiveness, voice, personality, stamina, and demeanor. After formal Hollywood auditions, Kubrick flew five finalists to London, selecting five-year-old Danny Lloyd from Pekin, Illinois for exhibiting exceptional concentration. Reportedly, he invented the device of talking to “invisible friend” Tony through his wiggling finger. He came up with Tony’s voice after being asked if he could do any other voices to represent Tony. Because British child actor laws forbade children from appearing in horror sequences and Kubrick felt protective, Lloyd believe he was in a drama about a family living in a hotel rather than a horror flick.

Halloran is Black in King’s novel, but Kubrick originally sought white actor Slim Pickens. Ben Vereen publicly accused Kubrick of thinking the story was too heavy for blacks. Pickens passed after his unpleasant experience with Kubrick for Dr. Strangelove. Pickens’ agent recommended Scatman Crothers. Crothers agent lobbied to little avail until asking Nicholson, who’d worked with Crothers on three prior films. to influence Kubrick. He was offered the role three weeks prior to filming.

Believing effects would render them farcical, Kubrick replaced the book’s attack by topiary animals with an imposing hedge maze. Wit it, Kubrick found his ending; he liked the fairy-tale-like resonance of Jack finding escape through the maze’s literal “dead end”. Miniatures were built to plan the cinematography, lighting, and camera movements. Kubrick used Garrett Brown’s Steadicam extensively with long takes capturing dreamlike “magic carpet” effects within the hotel and labyrinth. Brown’s latest model could shoot low to the ground, providing Danny’s perspective. A wheelchair-mounted Steadicam followed Danny tricycling around the Overlook’s corridors. Brown compared running during multitudinous takes manipulating heavy equipment to competing in the Olympics while playing a piano that’s in motion.

After production began, Nicholson became annoyed that Kubrick used actors rather than stand-ins to sit for monotonous lighting setups, told Kubrick that being a perfectionist doesn’t make him perfect. Kubrick explained that nobody’s nose lit like his. Kubrick required dozens of takes for many scenes. Kubrick wanted the “CRM” – critical rehearsal moment – something unexpected that emerged from constant experimentation. Nicholson groveled that realism was lost in repeated takes; Kubrick retorted that realism isn’t always interesting. Through repetition, actors lose self-consciousness, hitting their marks while saying their lines without thinking. Duvall later compared it to being in the film Groundhog Day.

Duvall started production in a happy mood. She felt silly emoting shock or fright, often getting the giggles. Kubrick’s patience wore thin and he let loose, really scaring her. His continued intimidation fed her insecurities. Making herself cry every day took a psychological toll, causing dizzy spells. Kubrick, deferential to Nicholson, afforded little sympathy for Duvall. Kubrick answered complaints with, “Nothing great was ever accomplished without suffering.” Duvall rationalized that Kubrick’s mercilessness was to maintain her hysteria. Kubrick reduced her dialogue because she struggled with self-consciousness. Johnson was disappointed to see the rounded Wendy she created reduced to tears and whimpers.

Crothers pled for mercy enduring endless takes. After falling forty times for Halloran’s violent death, Nicholson implored Kubrick to stop. Crothers incurred back pain requiring extensive chiropractic care. He was disappointed when Kubrick experimented with several endings, none resembling the novel or early scripts where Halloran saves the day. Halloran “shines”, knows the hotel’s history and is telepathically warned. Arriving defenselessly made little sense.

Script changes came nightly. Nicholson didn’t bother preparing until receiving the latest pages the day of filming. Kubrick respected Nicholson’s screenwriting experience, incorporating his ideas. A scene where Jack lambastes Wendy for interrupting his concentration came from Nicholson’s memory of yelling at then-wife Sandra Knight for doing the same. It was Nicholson’s idea to throw a ball against the walls of the Colorado Lounge, though he regretted it after performing so many takes he felt his arm would fall off. Nicholson once claimed to come up with the infamous, “Here’s Johnny!” line, but later said it was scripted. He also claimed to ad-lib the Big Bad Wolf dialogue from “The Three Little Pigs” when chopping through doors to get Wendy and Danny.

Notably, Jack plays ball with the hotel rather than Danny, who must entertain himself with his toys, tricycle, game room, maze, or TV. (Kubrick decided against using a scene of Danny in the game room where the machines appear to come to life). The Grady sisters invite Danny to play with them forever. Meanwhile, Wendy’s doing the caretaking work while Jack neglects every responsibility other trying to write. The Grady sisters’ look was influenced by Diane Arbus’s 1967 picture of identical twins and Kubrick’s picture of sisters holding hands from the 1940’s in “Look” magazine.

Johnson was disappointed that Kubrick shot but removed all allusions to the scrapbook detailing the hotel’s horrific secrets – murders, suicides, mishaps, scandals – and reports of supernatural occurrences. This treasure trove of ideas for Jack’s novel symbolized his fairy tale ‘poison apple’ – a tainted gift that costs his soul. Despite spending six weeks writing and replicating articles in the style of archival Denver newspapers, Kubrick removed it to delay revealing the ghosts as real, even if it left ghost identities unexplained. Duvall said the scariest moment to film was when Wendy sees the ghost of Halloran’s grandmother behind her in a mirror; she surmises it was cut because audiences wouldn’t recognize her. The scrapbook remains briefly visible but unexplained near Jack’s typewriter in the final cut.

Johnson posits another possibility as to whether the ghosts are real or imagined: they’re psychological projections that have real physical power. Shakespeare used ghosts as manifestations of the inner turmoil of certain characters, usually appearing as they go mad. Jack’s mind would be especially conducive. As a writer, he creates fantasy to escape his humdrum life. What occurs in the Overlook is a result of thoughts in his head, producing a feeling of deja vu. His lack of surprise and familiarity toward Lloyd the bartender suggests he’s imagining someone from his drinking days. A mirror’s presence whenever Jack encounters a ghost implies he’s talking to himself.

Fearing difficulty renting the room, Timberline Hotel management requested a number change to rooms they didn’t have – 237, 247, or 257. Kubrick chose 237. Early scripts had Jack encountering the living corpse of Grady’s murdered wife there. but Kubrick added an enticing, statuesque nude woman in ghost form that would be revealed in the mirror as a disfigured hag in her physical body. The scene convinced Jack that the spirit world is beautiful and exciting compared to the ugliness of reality.

Jack’s offer to trade hi soul for a drink symbolizes his desire to escape familial responsibilities. He’s tired of domestic emasculation, male insecurity, and artistic impotence that give him nothing in life worth writing about. The Faustian bargain extends toward Jack sacrificing his family for eternity at the hotel, living within an upper-class patriarchal society hobnobbing with “all the best people.” Wendy discovers that “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” typed on countless pages in various typographical arrangements (typed and photocopied by Kubrick’s secretary). Outed as a complete failure, Jack sees no way forward except to regress into the past. The ghosts appeal to Jack’s ambitions, inviting him to “play” “forever and ever” in a timeless afterlife within an exclusive society where he has the status and importance he’s longed for.

The film ends with a wall-mounted picture showing Jack attending a Gatsby-esque party at the Overlook on July 4, 1921 (“Independence Day”). Reality plays like a Shakespearean tragedy, Jack’s hubris stemming from overreaching ambition, but as a ghost, there’s a fairy-tale ending. It solidifies Kubrick’s theme of humanity’s incapacity to learn from the past and evil endlessly recurring. Jack is frozen, literally and figuratively, in a hotel built upon an Indian burial ground. Additional Indians were massacred during its building. Indian motifs abound, yet, interestingly, no Native Americans are depicted as ghosts. Johnson claims early drafts used Indian motifs as a broader critique of racism, fueling Jack’s “white man’s burden.”

An early script replaced Jack’s choice weapon from a roque mallet to a baseball bat, an American symbol while Wendy protected herself with an ax handle, a Native symbol. Wendy’s is shown occasionally wearing an Indian-style wardrobe, connecting oppressed people, and red to connect to “Red Riding Hood” in contrast to Jack’s “Big Bad Wolf.” However, Nicholson, a former volunteer fireman, adeptly handled the fireman’s ax, so they switched weapons. Jack is associated with canines – the wolf or coyote, which explains the several “Road Runner” cartoon allusions. Jack reading a Playgirl in the lobby of the Overlook might be indicative of his closet homosexuality. A scene of a man in a dog costume performing fellatio on a tuxedoed man is seen by Wendy, a potential projection of her fear that Jack was seduced by the life of wealth and privilege.

NOTE: Kubrick was once livid at Nicholson for asking for a few days off due to his back injury, because he saw him on television at Wimbledon with a girl on each side of him. Kubrick had an electrician named Bobby Tanswell with Nicholson’s build put on his jeans and boots so he could shoot the sequence of Jack being dragged into the food storeroom. Kubrick also wanted Tanswell to put on the bear suit and show his “bare” bottom while his head was in a man’s lap, but he refused, though it indicates Kubrick’s desire to connect Jack as that man.

Delays prolonged the shoot well beyond the initial four months allotted. Nicholson was out for weeks after aggravating his back jumping a garden wall behind his rented home. A fire caused by an electrical fault erupted near the end of principal photography, destroying an empty set. Despite only three minor scenes left to film, Kubrick had the insurance company pay $2.5 million to rebuild the entire set.

Composers Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind had only King’s novel for scoring ideas until rough footage was available months later. However, Kubrick later opted for pre-existing classical pieces, including “Dies Irae” at Carlos’s recommendation for evoking death, ghosts, and graves – specifically the “Berlioz Requiem”. Kubrick grew obsessed with the “Berlioz” arrangement, adding compositions from Krzysztof Penderecki, Bela Bartok, and Gyorgi Ligeti that meshed with its lower, slower tones, minimizing the original score.

The Shining was a modest commercial success, earning $44 million from its estimated $19 million spent. After its New York premiere, Kubrick removed the two-minute epilogue where Ullman visits Wendy and Danny in a California hospital. Ullman reveals they never found Jack’s body then tosses Danny a tennis ball, suggesting he masterminded what transpired. Kubrick removed another 25 minutes for overseas showings. Gone was Danny’s pediatric examination, the hotel tour, most of Halloran’s explanation of “shining”, sequences involving television, Wendy’s notion to leave in the Sno-Cat, and Halloran’s return journey.

Critics skewed negative on The Shining upon its release, expecting something more, or different, or faithful to King’s book. It became Kubrick’s first film since 1957’s Paths of Glory without Oscar nominations. Worse, it received Razzie nominations for Worst Director and Worst Actress.

King was especially critical, accusing Kubrick of dismissing effective horror methods as too easy, toying with audience expectations instead of grabbing them by their throats. He crafted a technicolor “Twilight Zone,” emphasizing arresting pictures and hollow plot twists. Kubrick’s pragmatism prevented him from embracing the supernatural elements, exploring domestic tragedy rather than horror. The Shining was like sitting in a luxury vehicle without an engine; you can admire the upholstery, but can’t drive anywhere. King called Nicholson too old for a former hippie idealist, too flamboyant for an ordinary man, too wild-eyed to think he wasn’t already crazy. King suggested Martin Sheen, Jon Voight, or Michael Moriarty. Many have associated Jack as King’s alter ego in the book, and Kubrick’s in the film. He characterized the change to Wendy as misogynistic, only existing to scream and be stupid.

Kubrick countered that his film is more horrific emotionally and intellectually, about horrors that happen between people, not the technical ability to make audiences jump. It’s not dark and shadowy; the white snow and well-lit interiors hide evil in plain sight within the people around us every day.

Over time, the reputation of The Shining skyrocketed as the “Masterpiece of Modern Horror” it was presumptuously marketed as. Nicholson observed that critics tended to slam Kubrick’s films upon release then proclaim them brilliant months or years later.

MPAA Rated: R for disturbing violent content and behavior, bloody images, graphic nudity, and strong language

Run time: 146 min.

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, Danny Lloyd, Scatman Crothers, Barry Nelson, Philip Stone, Joe Turkel

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Diane Johnson (based on the book by Stephen King)