Poltergeist (1982)

Steven Spielberg’s intended follow-up to Close Encounters of the Third Kind was a darker alien-invasion concept called Night Skies. The story idea came during Spielberg’s UFO research, stumbling across the Kelly-Hopkinsville incident in which aliens terrorize a farm family in 1950s Kentucky. Under contract to direct his next feature for Universal Pictures, Spielberg planned to produce but not direct Night Skies for Columbia.

For the director, Spielberg first pursued Tobe Hooper, who he admired for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Hooper was directing The Funhouse for Universal and was inhabiting Robert Wise’s office. Within Wise’s desk was a textbook about poltergeists he’d used for his 1963 chiller, The Haunting. Hooper thought Hollywood was long overdue for another great ghost flick. Hooper and his mentor, director William Friedkin, contemplated presenting a ghost story to Universal done with their immersive sensurround sound process. Hooper didn’t have anything worked out but the premise of people haunted by the spirits emanating from a nearby cemetery.

Hooper told Spielberg aliens weren’t his thing. Maybe if they were ghosts. Hooper mentioned he was currently working on a ghost story in the vein of The Haunting, a favorite of Spielberg’s. Born with tremendous curiosities and fears, Spielberg had a lifelong fascination with ghosts. He had an experience in 1972, after directing his made-for-TV horror flick, Something Evil. While in Texas scouting locations for The Sugarland Express, he experienced an eerie presence in his hotel room that disappeared when he focused his eye on it, after which, the room turned abnormally chilly. Spielberg fled, but the car wouldn’t start, another scare before he secured a ride to another hotel.

Exhausted by the violent Raiders of the Lost Ark, Spielberg’s interest in the dark horror of Night Skies collapsed in favor of making its heartwarming subplot involving an alien befriending a troubled boy the main focus. He pitched his story change to Columbia, but they didn’t want a kid’s version of another film they had in development, Starman. Universal bought the Night Skies project out for Spielberg to direct, while Spielberg prepared a Special Edition of Close Encounters to sate Columbia’s sequel desire. Spielberg then flipped the aliens to ghosts as Hooper suggested using the family-under-siege premise and sold the treatment he wrote to MGM as Night Time. Hooper stayed in contact while Spielberg shot Raiders, excited to work on his ghost story with the hottest filmmaker in the business.

Spielberg wrote several “stream of consciousness” story outlines over the next several months, changing the title to It’s Night Time. Unlike other haunted house films that showcased a spooky, isolated mansion before seeing the ghosts, Spielberg wanted his haunting within a suburban home like he grew up in, with an ordinary family thrust into extraordinary circumstances.

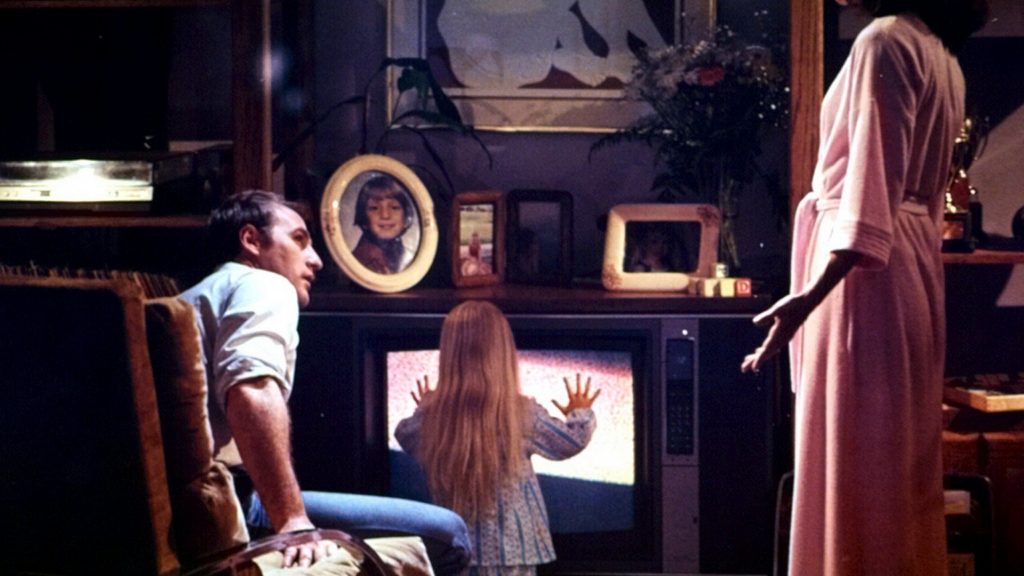

Spielberg’s preliminary story concentrated on a couple, Steven and Nora Freeling, and their four children living in the fictional Chicago suburb of Vista. Eerie shapes are seen through the static of the TV. Random phone calls occur with static on the other end. Furniture is rearranged. Items go missing. The TV changes channels on its own. Strange entities are briefly glimpsed around the home. Parapsychologists from a nearby university are called in. The family members’ get possessed by unseen forces. An archaeological dig unearths the skeletal remains of pioneer settlers massacred by Natives nearby. A psychic named Tagina Barrins arrives at the Freeling home, communicating to their spirits through the TV static.

Spielberg sought Stephen King to script, but he was too expensive. He then hired the screenwriting team he’d wanted to use for Always, his remake of the 1943 film, A Guy Named Joe, Michael Grais and Mark Victor. The screenwriters imagined a slasher formula, killing the family members one by one but Spielberg thought no more than one should die. They chose the youngest daughter, Carol Anne, who could come back as a ghost.

Once completed, Spielberg wasn’t keen on their grisly script and decided to rewrite it himself. He researched poltergeists, noting that they made their presence known primarily to young children. He thought about how frightening it would be for the mother from Close Encounters if her child were abducted by ghosts instead. What if that child were Carol Anne?

Working with Hooper, Spielberg centered the plot around the family losing Carol Anne to the spirit realm and trying to get her back. This reminded Spielberg of the “Little Girl Lost” episode of “The Twilight Zone,” written by Richard Matheson, who wrote Spielberg’s TV movie, Duel. At Spielberg’s request, Matheson supplied a Betamax tape of the episode. Spielberg returned it without comment but several key elements in his revised script bear a striking resemblance to the episode – a beatific young girl with bangs, her disembodied crying voice, invisible portals within the house, a parent physically going through the portal to rescue their daughter. (Matheson later speculated that Spielberg hired him for Twilight Zone: The Movie and “Amazing Stories” as unspoken compensation for lifting his concepts.) Spielberg worked on his revision for five evenings, reading it every morning to the co-producers who’d moved into his home temporarily for immediate feedback.

In the completed script, we find a family of five, the Freelings, living in the fictional suburbia of Cuesta Verde. However, strange events take place in their new house, including five-year-old Carol Anne conversing with “TV people” through the static on their television. Things take a deadly turn when the tree outside becomes animated and goes after the middle child. The boy is saved, but their Carol Anne goes missing, stolen into another dimension by forces unknown, though her voice can be heard communicating through the television. Parapsychologists from Stanford come to investigate the strange phenomena but the forces that currently dominate the house prove much stronger than anything they’ve encountered, requiring the services of a clairvoyant spiritualist.

Spielberg didn’t direct Poltergeist for several reasons. The main one was Spielberg’s contractual obligation to Universal for his next directorial effort. Plus, it was worked on with Hooper in mind as director from its inception as Night Skies. He also had too much going on after post-production for Raiders, including pre-production on E.T., and developing a “Peter Pan” musical collaboration with Quincy Jones (which morphed into Hook) and that remake of the 1943 film A Guy Named Joe (trivia: the movie appears briefly on the Freeling TV in Poltergeist).

Spielberg had executive-produced films before where his directors had ample freedom. However, Poltergeist was personal. It contained his ideas, his childhood experiences, his fears. He determined to line-produce, collaborating on storyboarding, casting decisions, and location scouting. The exteriors were in Simi Valley and Agoura Hills, CA, and interiors at MGM Studios because the intricate effects required manipulation from above the “ceiling” or beneath the floor.

Spielberg stayed recharged alternating between E.T., exploring his boyhood hopes and dreams, and Poltergeist, representing his phobias and nightmares. Spielberg calls Poltergeist his revenge on television, which he furtively watched when his disapproving father was away. Spielberg remembered adjusting the antenna and seeing the “ghosts” of people in faraway broadcasts within the snowy static.

In Poltergeist, TV is the family’s main group activity. Steve’s friends come over for the big game, and his neighbor babysits his kid with Mr. Rogers. A scene later has neighbors having a tug-of-war of sorts with the television remote controls shows TV’s propensity to divide us. TV has gone from a side source of entertainment to be the glue that binds American society together, and wedges us apart, prior to the internet. A theme of Poltergeist is that the more time one spends through this portal, the less grasp one has on the real world.

Many childhood phobias factor into Poltergeist. Spielberg feared the ominous shadows cast by the raggedy maple tree in his yard as a kid. Michael Grais had a childhood experience of a tree branch breaking through a window as he was home alone during a thunderstorm. A moment when a drinking glass breaks in Robbie’s hand came from Hooper’s own childhood experiencing kitchenware shattering for no discernible reason.

Spielberg’s greatest childhood fear, clowns, is explored through a disturbing-looking clown doll in Robbie’s bedroom. In addition to fearing what lied under his bed or in his closet, there was a crack in young Spielberg’s bedroom wall that he imagined was a portal to a realm inhabited by little Hieronymous Bosch-like beings whispering to him to come in and play.

The film’s opening displays the patriotic TV station signoff, a comment on television’s national importance to Americans. Spielberg trimmed an extended sequence to the final shot of the father pushing the TV out of their hotel room – after a beat, the TV rolled of its own volition further down the balcony, suggesting things aren’t really over but it raised too many questions than it was worth. The satire explores TV as the portal of evil that steals children away from their families into other dimensions. It divides their closeness with each other, with their neighbors, and with the nation as a whole, a distraction to tanalize our attention into selling us products. By becoming consumers, we become the consumed.

Poltergeist taps into the anxiety for children of the 1960s who outgrew their youthful idealism, buying into the American Dream mythology promoted by Ronald Reagan, who promised corporate freedom from governmental regulations governing environmental protection. The cost-cutting measures employed by the real-estate company cause the catastrophe, moving only the headstones of the cemetery and building their housing project atop the bodies. Symbolically, something’s rotten underneath this American Dream that’s disrupting the unity of the family and community. Greedy corporations have no respect for the living, much less for the dead. Meanwhile, the middle class always seems to pay for their transgressions.

Poltergeist also taps into a parent’s greatest fear of being unable to protect their children from the world’s ills. Carol Anne’s frightened voice emanates from the TV set, tormenting her anguished, helpless parents.

Shirley MacLaine declined the Diane Freeling role because she felt it was too violent and portrayed the spirit realm negatively. He then cast JoBeth Williams after enjoying her performance in 1980’s Dogs of War, especially during a scene in which she gets into a fight with Christopher Walken’s character that ends in violence. Fortuitously, Spielberg caught that film in London because that scene was omitted for the American release.

Spielberg discovered Heather O’Rourke in the MGM commissary, as she and her mother visited Heather’s older sister Tammy, a child actress appearing in Pennies from Heaven. Spielberg waved at the angelic Heather from another table, then had co-producer Frank Marshall walk over to find out more then make the introduction leading to an audition. Drew Barrymore was also considered, but Spielberg preferred O’Rourke because her character needed to be angelic such that the spirits would follow her to the light of the afterlife. He put Barrymore in E.T.

Oliver Robins was cast after several callbacks. After Hooper told him that the scream was the most important acting element in a horror movie, Robins worked with a coach to perfect a blood-curdling scream and won the part. Robins had a near-death incident when the clown prop coiled around his neck became too tight. Robins screamed he couldn’t breathe, which Hooper and Spielberg mistook as fantastic improvising. Only when Spielberg noticed the boy’s face turning crimson did he quickly intervene.

Spielberg’s contract with Universal stipulated that he couldn’t work on other films while making E.T., which was scheduled to start production two weeks after Poltergeist‘s ended. When E.T. was delayed, Spielberg remained on Poltergeist for the duration. Spielberg compared himself to David O. Selznick, a hands-on producer working with his director to achieve success. Spielberg mapped camera setups and designed specific shots, sometimes doing pickup work while Hooper worked with the main actors. A visiting Los Angeles Times reporter grew confused enough to write a piece that sparked a controversy that continues to exist about who was actually directing the film.

Spielberg was on set every day, save for a two-day jaunt to Hawaii to build a sandcastle with George Lucas for luck prior to attending the premiere of Raiders (Lucas had done that before Star Wars). Due to Hooper’s amiability, Spielberg felt open to make decisions and give direction as needed. Although Spielberg had the final say, Hooper called it the best working relationship he’d ever had with a producer.

Rumors spread of Spielberg being the primary director, going around Hooper to achieve what he wanted. As the soft-spoken Hooper wasn’t a commanding presence on a Hollywood set, Spielberg felt compelled to step in to address conflicts. Spielberg says his interjections had less to do with Hooper’s competence and more with his own bullishness. Spielberg’s mother relates how Steven’ learned to be pushy making high-quality home movies as a teenager. Pushiness got a hospital to let him shoot in one of their wings and an airport to close a runway for him. Spielberg says Hooper always voiced agreement and that he’d have left the set if Hooper voiced any complaint with his interjections.

The general consensus is that Hooper primarily directed the actors and Spielberg the technical crew. Co-producer Frank Marshall metaphorically described it as Hooper having a close-up lens and Spielberg the wide-angle.

The rumor among industry insiders was that Spielberg took control when Hooper was coked out and couldn’t focus, something that resulted in his removal from prior projects. Although typically grounds for a director’s removal, Spielberg formally assuming director duties wasn’t a viable option. In addition to Spielberg’s contractual obligation to Universal on his next directorial effort, the DGA forbade anyone already involved in a production from replacing a director, including producers. They also wouldn’t allow anyone to direct two films simultaneously. With E.T. looming, Spielberg didn’t have time on his side. His best path to success required shepherding Hooper to the finish line.

Writer Bob Gale called the set’s atmosphere uncomfortable. When Hooper gave direction to any crew member, they looked to Spielberg for his OK before proceeding. Screenwriter David Giler, who played an extra for the football party sequence, quipped that he now knows what a producer does: sets up the cameras, tells the actors what to do, then lets the director say, “Action!”

Hooper spent 2.5 months assembling his cut with Spielberg’s editor Michael Kahn, then was excused. Spielberg supervised the final cut and guided the rest of the post-production, including the Oscar-nominated visual effects (from Industrial Light and Magic), sound effects, and score. Composer Jerry Goldsmith says he never worked with Hooper. The only time he saw him was at an early screening where Spielberg ignored his presence; Hooper left within the first five minutes.

The financially struggling MGM demanded a PG-rating to draw in children and families. Prior to the production, Spielberg removed a few harrowing scripted sequences, one where Diane Freeling is invisibly raped (this changed to being pushed to the wall and ceiling) and another of the paranormal investigators are attacked by spiders. Nevertheless, the ratings board slapped Poltergeist with an ‘R’ rating for overall intensity and peril involving children. Spielberg and MGM appealed, arguing that the film contains no nudity, sex, language, and no one is killed who isn’t already dead. The board unanimously reversed its decision.

Hooper asserted he did everything contractually required as the director, and a DGA investigation into the matter reaffirmed his credit. He considered Poltergeist a creative collaborative effort similar to the Spielberg/Lucas partnership for Raiders of the Lost Ark and that questions on who’s film it was weren’t good for business. MGM’s publicity wing promoted Poltergeist as a Spielberg film because he was the hottest filmmaker in Hollywood. They cherrypicked behind-the-scenes publicity photos and documentary footage of Spielberg taking charge, often as Hooper stood around or received instruction from him. Spielberg saw little incentive to squash rumors that helped the bottom line.

Hooper filed no complaints until a trailer was released displaying “A Steven Spielberg Production” twice as large as “A Tobe Hooper film”, violating DGA rules. MGM was forced to redo the trailer, issue Hooper $15,000 along with a full-page apology in three major trade magazines. Spielberg published an open letter to Hooper in appreciation for allowing his creative involvement as the writer-producer. He claimed the media misinterpreted their unique, creative collaboration. The authorship controversy caused Spielberg to never again let anyone else direct something he wrote.

The publicity wasn’t good for Hooper’s career, with Spielberg receiving the entire limelight for Poltergeist‘s success. The only thing Hooper earned was a reputation that he couldn’t command a big-budget movie set. Spielberg made amends, hiring Hooper to direct an episode of “Amazing Stories” in 1987 (“Miss Stardust”, cowritten by Richard Matheson) and “Taken” in 2002.

Poltergeist is a gem, horrific but palatable for audiences that normally avoid the genre. Emphasis is strong on character development among the family, which elevates our fear during frightening moments.

What sets Poltergeist apart from other horror films is the taut pacing. Most quiet moments are near the beginning, drawing you into the characters’ day-to-day lives. As the climax develops, it rips wide open, culminating in cataclysmic events that deliver terror, wonder, and awe.

Despite the PG rating, Poltergeist is intense enough to give nightmares to the impressionable. Classic horror elements mesh perfectly with the newer style, but most of the points are scored through visual storytelling and characters.

Poltergeist plays to provoke audiences rather than for logic. However, the entertainment value is never really in question, and compared to most other entries in its genre, particularly among the trashy slasher films of the early 1980s, this is a superior entry worthy of bestowing heaps of praise for escalating fear and nightmares to last a lifetime.

Qwipster’s rating: A+

MPAA Rated: PG for gore, scary images, language, and a scene of drug use

Running Time: 114 min.

Cast: JoBeth Williams, Craig T. Nelson, Beatrice Straight, Heather O’Rourke, Zelda Rubinstein, Oliver Robins, Dominique Dunne, Richard Lawson, Martin Casella, James Karen

Director: Tobe Hooper

Screenplay: Steven Spielberg, Michael Grais, Mark Victor