Rocky IV (1985)

Even though Stallone asserted that the Rocky series would conclude with Rocky III, its immense success led MGM/UA’s troubled financiers to clamor for Rocky IV. However, approaching 40 years old, Stallone couldn’t envision further developments in Rocky’s boxing journey beyond retirement. United Artists offered him a fortune to bring Rocky back to the ring: $15 million, $20 million, $24 million. Stallone rejected all the initial offers. Nevertheless, when numerous news stories arose about real-life people inspired by Rocky, his determination softened as he recognized that Rocky wasn’t merely a movie character. He had evolved into a symbol of hope for anyone striving to achieve their dreams. Extinguishing that hope felt selfish.

Stallone contemplated continuing Rocky’s next trilogy in the political arena instead of in the boxing world. The first film would bring Rocky back to Philadelphia to run for mayor. The trilogy would conclude with Rocky becoming a global diplomat. However, in January 1983, MGM/UA presented Stallone with an offer he couldn’t refuse: no upfront salary but 50% of the gross once MGM/UA recouped its production expenses. The stipulation: it had to be a boxing movie, not a political drama. If Rocky IV performed as well as Rocky III, Stallone stood to make $45 million. He renegotiated the deal because he didn’t want to depend on a studio-funded accountant for his financial future. Instead, he would receive $15 million upfront and 15% of the total gross while committing to keep production costs under $12.5 million. United Artists aimed for a 1984 release, but Stallone’s commitments delayed it to late 1985. Stallone insisted again it would be Rocky’s final bout.

Stallone believed Rocky would return to the ring only to fight for something greater than himself. As with previous entries, Stallone drew inspiration from autobiographical elements for Rocky’s story. In 1982, his second son, Seargeoh, was diagnosed with autism. As Seargeoh’s ability to be present and communicative diminished, Stallone felt cursed. Sly’s mother, Jacqueline, reassured him by saying it was God’s plan for someone as famous and wealthy as him to have an autistic child, as he could help raise awareness. Sly and his wife, Sasha, launched a series of fundraising initiatives to support research through the Stallone Foundation for Autism. Stallone believed that awareness could soar if Rocky Jr. was diagnosed with autism in Rocky IV, and Rocky and Adrian struggled similarly to adjust. In this concept, Rocky retires to care for Junior with Adrian in their mansion on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Eventually, Rocky makes a comeback to the ring for a high-profile exhibition match to raise funds for a cure.

As Stallone brainstormed about what that high-profile match might be, news stories emerged regarding the Soviet Union launching a retaliatory boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics in response to the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. Olympic fans worldwide expressed deep disappointment that some of the best athletes would not compete again due to politics. This starkly contrasted with earlier times when nations at war still participated in the Olympic Games, as it provided a unique platform to boost national pride during difficult times. Stallone had previously considered Rocky facing a Russian goliath in the Roman Coliseum for Rocky III. Although the Coliseum concept wouldn’t fit their budget, he liked the idea of Rocky competing in foreign territory, especially against a hostile crowd he ultimately wins over. Rocky’s exhibition match could be against Russia’s potential Olympic boxing champion for a bout set in Moscow.

Stallone recognized that the bout would carry political implications. He recalled the two boxing matches in the 1930s between Black American Joe Louis and white German Max Schmeling. After Schmeling won the 1936 fight, the Germans exploited his victory for propaganda, promoting their ideas of genetic superiority. When Schmeling lost the 1938 bout in the first round, he was ostracized by the Nazis. There would be similar nationalistic sentiments riding on a match between America’s best fighter and Russia’s, recalling ancient times when rival tribes selected their best warrior to fight one-on-one instead of all-out war. The Soviets would especially want Rocky destroyed, as he was the epitome of capitalism’s success, having risen from poverty to build his fortune through opportunity and determination.

Meanwhile, the US would want a Rocky victory in Moscow to stoke political upheaval in the Soviet Union by symbolically demonstrating to the oppressed Russian populace that underdogs can topple giants. Stallone created a scenario where former United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (whom Stallone hoped would portray himself) urges Rocky to represent America in the fight. The Russian champion, Drago, is a government lab-created superhuman that Russia aims to use as a propaganda tool and a test run for developing a new army of bio-enhanced supersoldiers.

Stallone envisioned the Moscow arena entirely decorated in Communist red, except for Rocky, who would don the stars and stripes of America, as showcased by Apollo Creed in the original Rocky. This inspired Stallone with another story idea to further raise the stakes and solidify Rocky’s commitment to what appears to be a suicidal match. The Russians actively seek to challenge professional boxers for Drago to face in exhibition matches, generating publicity for his entry into the professional circuit against the world champion. After the boxing commission prohibits active boxers from participating, Apollo, as a retired boxer, challenges Drago, eager to return to the spotlight and, due to the political nature of the fight, to secure his historical legacy so he will never be forgotten.

Although the Russians are reluctant to fight a has-been, Apollo’s showmanship provokes them into accepting his challenge. Rocky agrees to serve as Apollo’s manager. However, Drago proves too powerful in the match, devastating Apollo and leaving him permanently disabled. Rocky feels accountable for not stopping the fight sooner, forfeiting his title to challenge Drago. On his way to Moscow, Rocky stops in Rome to visit the Vatican and receives the Pope’s blessing. As Apollo manages him from his wheelchair at ringside, the Rocky/Drago bout begins, with Stallone modeling the momentum of the ensuing fight after the 1975 bout between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, known as “The Thrilla in Manila.” Rocky breaks Drago’s spirit by demonstrating that he isn’t as invincible as previously thought, while the Russian crowd starts to cheer for Rocky to win the fight of his life.

As Stallone continued to work on his other projects, he asked his wife, Sasha, to attend auditions in Los Angeles, New York, and Toronto to find potential Dragos: well-built, European-looking men, 6’3″ or taller, preferably able to speak a Slavic language. Many tall men from boxing, wrestling, football, and other athletic sports auditioned, but finding those with the right look who could convincingly act with a Russian accent proved challenging. Sasha’s mission was aborted when she filed for divorce, cited as irreconcilable differences, publicly described as issues stemming from Seargeoh’s deterioration, though privately it was again due to Sly’s infidelity. His philandering was notorious, including a year-long affair with 20-year-old Vancouver stripper Loree Menton. Sasha received a $32 million settlement, which included custody and child support for their two sons, as well as funds to ensure Seargeoh received the full-time care he needed. Meanwhile, Stallone distanced himself from the autism substory for Rocky IV.

Stallone briefly dated Mary Hart from “Entertainment Tonight” before meeting 21-year-old Danish model Brigitte Nielsen in New York, where she was promoting her debut starring role in “Red Sonja.” After discovering he was in town, Nielsen tried to meet Stallone by leaving notes with her phone number for him at the hotel he was staying at. The notes mentioned that she had always been a massive fan of his, claiming she had written to him since she was 11 (two years before “Rocky”) and had named her son Sylvester (though he was named Julian; she later said her husband vetoed the name, Sylvester). After three days without a response, she left an envelope containing a provocative bikini picture. Stallone finally called her, they met, and their romantic relationship quickly blossomed. She soon moved in with Stallone, leaving her husband and baby behind in Denmark. Stallone managed her acting career, advising her on promoting herself through press interviews for “Red Sonja.“ He created a role for her in “Rocky IV” as Drago’s Olympic swimming champion wife, Ludmilla, so that they could spend more time together. Stallone also hoped that his eldest son Sage would portray Rocky Jr. to have more time with him, but as production approached, Sage decided to back out, not wanting his schoolmates to treat him any differently or unkindly. Another child actor, Rocky Krakoff, stepped in for Sage.

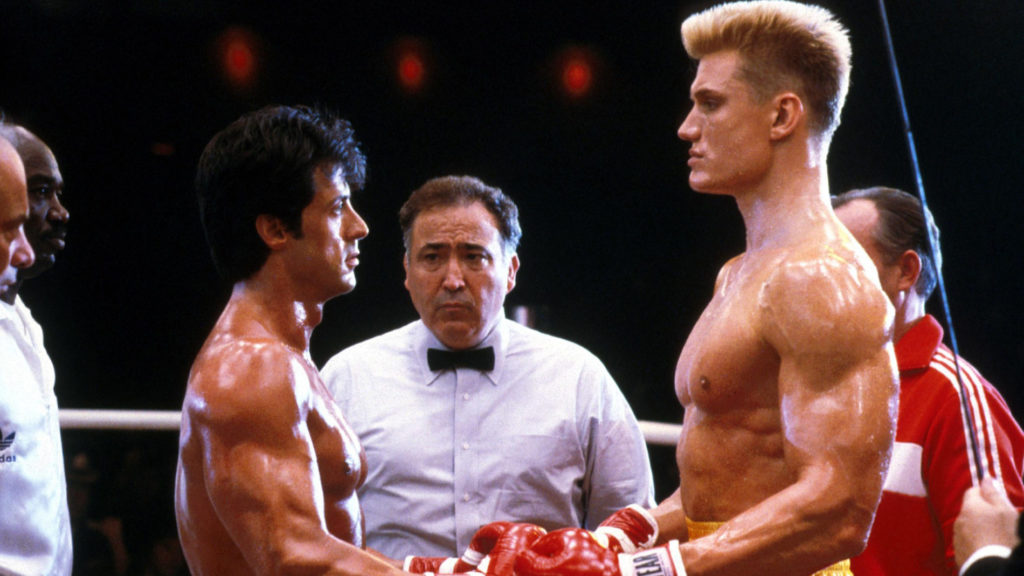

In December 1984, Stallone discovered his Drago: 6’5″, 240-lb. Swede Dolph Lundgren, a former chemical engineering student, karate black belt, and professional kickboxer who worked as a club bouncer and was also engaged to avant-garde model/singer/actress Grace Jones. Lundgren caught the acting bug after being inadvertently drafted by John Glen, the director of the James Bond film A View to a Kill, to take on a small role while he was watching Grace Jones. Glen was impressed by Lundgren’s screen presence and ability to follow cues, suggesting that he would excel as an actor.

Lundgren began taking acting lessons from Jones’s coach, Warren Robertson, who circulated his photos and encouraged him to audition for various casting calls. One of these auditions was for a boxing movie. Lundgren was quickly informed that he was too tall, but when he saw a sign that read “Rocky IV,” he felt compelled to pursue it further, being a massive fan of the series. Robertson sent Lundgren’s portfolio to him through an inside connection. Six months and thousands of auditions later, Stallone called in Lundgren for a look.

Lundgren fine-tuned a Russian accent through coaching from Robertson and prior interactions with many Russian immigrant neighbors living in Brighton Beach. Already fluent in four languages, Lundgren quickly adapted to various dialects. On the day of Lundgren’s audition, Stallone was also considering two professional wrestlers: Nelson Simpson, auditioning in his faux-Russian pro-wrestling persona as Nikita Koloff, and Kerry Von Erich, who was recommended by Stallone’s good friend from the wrestling world, Terry Funk (who had suggested Hulk Hogan for Rocky III). Koloff was viewed as too bulky, especially compared to Stallone, while Kerry, although a favorite of Mr. T and his wrestling-loving mother, struggled with memorizing lines and speaking Russian.

Unlike the wrestlers, who appeared to be wildly overacting like Slavic versions of Clubber Lang, Lundgren followed Robertson’s advice to portray Drago with minimal emotion. Drago is an undefeated champion boxer who feels invincible, and his confidence means he doesn’t need to exaggerate his intimidation. To deliver a nuanced performance, Lundgren conducted extensive research about the type of person Drago would be. He didn’t see Drago as evil but a pawn manipulated by a malevolent regime. Stallone was impressed with Lundgren, likening him to a giant Kurt Russell.

Unbeknownst to Stallone, Robertson had already secured a minor role for Lundgren in Rambo II as Sergeant Yushin. When Stallone called Lundgren to inform him that he had landed the Drago role and needed training to gain at least ten pounds of muscle, Lundgren mentioned that he was preparing to fly to Mexico to face him in Rambo II. Stallone wanted Rocky IV to be his debut, so he bought out Lundgren’s $6,000 contract and gave Yushin’s role to his bodyguard, Voyo Goric.

For Drago, Lundgren earned $100,000 and a small percentage of merchandise featuring his likeness. He trained with Stallone for seven months under the direction of Larry Holmes’ trainer, Richard Giachatti. Lundgren stayed in Stallone’s guest house after Grace Jones frequently had him out all night partying, which he worried might get him fired for lack of sleep. He and Stallone watched tapes of classic boxing matches at night to practice choreography.

Lundgren was intelligent, handsome, and sophisticated, leading Stallone to revise the primitive, brutish Drago character. Lundgren’s Drago would embody the pinnacle of perfection through genetic testing, science, and advanced training and conditioning for the Russians. A theme emerged of humanity versus technology, and nature versus science, evident throughout the training montages. Drago’s taciturn mystique evoked fear, resembling a machine more than a man, primarily depicted through cinematic techniques like montage and music.

Stallone explored various options for representing Russia, including locations in Yugoslavia, Norway, Austria, Canada, and the United States. Ultimately, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, was chosen to depict Russian exteriors for a barn and cabin. Unfortunately, the weather was unusually warm and sunny, necessitating snow machines to create the illusion of freshly fallen snow. Vancouver’s Agrodome was transformed into a Russian boxing venue. The production worked with local food banks, offering $3 for each “Slavic-looking” individual they recruited. Extras were not paid, but were given a box lunch and unlimited snacks to represent the Russian crowd. They were asked to dress as Russian commoners, wearing dark clothing, babushkas, and fur hats, yet many arrived in jeans, sneakers, and trendy hairstyles. The heat, boredom, and sporadic fights caused hundreds to leave early, prompting the offer of cash and door prizes such as TVs, stereos, and food processors to entice them to stay.

Stallone wanted Russia’s boxing operation to look futuristic and advanced, and the regime fully supported promoting Drago as a symbol of Russian might. Meanwhile, Rocky was alone, only wanting to avenge Apollo and defeat this evil empire fueling his fire. The fight arena was less a traditional boxing match than a political convention.

Drago’s Achilles’ heel is his belief in invincibility, as he has never experienced pain. When Rocky begins to land punches, the illusion crumbles, and Drago realizes he has been deceived by a regime with malicious intent and will soon be discarded for failure. Drago loses because, unlike Rocky, he stops believing in what he is fighting for.

Stallone watched the middleweight championship bout between Marvin Hagler and Tommy Hearns, billed as “The Fight” but later referred to as “The War.” The boxers disliked each other so intensely that they abandoned traditional strategy and just went at it. This motivated Stallone to eliminate fight choreography for the beginning of the first round, allowing unscripted punches to connect. The rules prohibited hard hits to the head, while body shots could be delivered at full strength. Stallone also asked for close-up hits filmed in slow motion to ensure there was no doubt they were real. For the montage of Drago defeating his sparring partners, stunt performers and club fighters were hired to take full-power punches for $500.

Carl Weathers wasn’t fond of the less structured approach to fighting. Lundgren remained in character on and off-screen, and all Weathers knew about him was that he was a kickboxing champion with no acting experience. After Lundgren unexpectedly threw Weathers three feet into the air, slamming him against the corner of the ring, Weathers walked off, threatening to call his agent and quit, leaving the set for several days before returning to honor his contract. Years later, Lundgren and Weathers had a friendlier rapport while appearing on Comicon fan panels.

In terms of Apollo’s fate, Stallone transitioned from depicting Apollo’s disability in a wheelchair to his death, as he felt Rocky needed to bear a more profound sense of responsibility and ultimately confront Drago. Stallone later regretted this decision, believing that Apollo’s loss hindered him from developing a more compelling character arc for a fighter who could never return in subsequent films.

The real hitting resulted in multiple injuries for Stallone, particularly bruised ribs. One day, Stallone claimed his vision was so blurry that he saw three Lundgrens at once, joking that he’d keep going by hitting the one in the middle (a line Paulie uses in the film). The worst damage came from Stallone’s chest one night. Nielsen, tired of Sly keeping her awake with his howls of chest pain, insisted he go to the hospital, where they discovered that the pericardial sac around his heart was swelling and bleeding due to a punch that pushed his diaphragm into his heart, slamming it against his breastbone. The trauma is similar to that of car accident victims who take a steering wheel to their chest on impact (Stallone joked that he was hit by “A Streetcar Named Drago”). The doctor said that his heart might have continued to swell if he hadn’t gone to the hospital until it stopped beating altogether. Production was suspended for two weeks, with Stallone in the ICU for nine days. Sly credited Nielsen with saving his life. Although they were still married to others, Stallone proposed, and they married once their divorces were finalized shortly after the release of Rocky IV.

One addition to Rocky’s entourage is a talking robot named Sico, introduced for comic relief. Stallone contacted its creator and operator, Robert Doornick, after seeing him on a talk show discussing how the robot could help autistic children communicate. To have Sico available to work with Seargeoh and promote better communication, Stallone offered Doornick a role for Sico in the film, a birthday gift for Paulie that would humorously drive him crazy. Sly became enamored with the robot, drafting new scenes, some of which he edited out for detracting from the dramatic flow. While collaborating, Doornick and Burt Young casually developed plans to spin off their odd-couple interactions into a TV sitcom. Doornick wrote a pilot, but the project never came to fruition.

During editing, Rambo-mania was sweeping across the United States, causing Stallone to embrace this wave of Reagan-era patriotism that encouraged Americans, who had felt restrained throughout much of the 1960s and 1970s, to cheer for themselves. He pared away at dialogue, communicating through flag-waving imagery paired to music-video montages energized by its driving soundtrack.

Stallone and composer Bill Conti had a falling out over financial disagreements stemming from Stallone’s limited use of Conti’s scoring for Rocky III, opting for pop soundtrack selections. Stallone replaced Conti with Vince DiCola, a musician who was a friend of Sly’s brother Frank and composed the hit “Far from Over” for the Staying Alive soundtrack. DiCola blended Conti’s fanfare style with his influences from 1970s rock and pop, particularly that of Gino Vanelli.

The original title for Survivor’s hit “Burning Heart” was “The Unmistakable Fire.” Stallone requested the title change after suggesting a shift from the lyric “human heart” to “burning heart.” Another hit from the soundtrack was James Brown’s “Living in America,” featuring a lip-synced performance by Brown himself in the movie. Brown’s performance evokes memories of his appearance in 1975, singing the national anthem before the fight between Muhammad Ali and Chuck Wepner, which inspired the original Rocky. The song became Brown’s highest-charting single in twenty years and was later parodied by Weird Al Yankovic as “Living with a Hernia.”

Rocky IV broke the record for the highest-grossing film released on a three-day weekend with $20 million and would become the highest-grossing box-office entry in the Rocky series. However, it fared the worst when it came to critical acclaim. It received a whopping nine Razzie nominations. Stallone won for Worst Actor and Worst Director, Nielsen for Worst Supporting Actress and Worst New Star, and DiCola for Worst Musical Score. Worst Picture and Worst Screenplay also went to Stallone but for Rambo II.

This lean film prefers montage over dialogue at 91 minutes, the shortest of the series. As with Rocky III, the antagonist seemingly comes out of nowhere, with little mention of his past. We root for Rocky mainly because, after three previous films, we have already grown to like him. Without any redeeming features in his opponent, our interest in the final battle is secure.

Rocky IV doesn’t lack entertainment value. The formula remains compelling, and the production and editing are slick. Once again, the fight scenes resemble professional wrestling matches, complete with body slams. No defensive boxing strategy is used, as Rocky blocks an incoming punch only with his face. Fortunately, Drago appears to share the same masochistic approach.

Despite being arguably the weakest installment in the series, newcomers Lundgren and Nielsen deliver a formidable screen presence that contributes to its watchability. Any similarity to the spirit of the original 1976 Rocky is, at best, tangential. Stallone’s most original idea comes in the film’s final moments, where he injects Rocky’s message about setting aside hostilities to the world. However, since this resolution comes through violence, the message feels hollow. Nonetheless, Ronald Reagan would openly commend Stallone’s efforts with this film (and Rambo II) for showcasing the true American spirit, which is essentially about overcoming obstacles by destroying them.

They say that the legs are the first to go for aging boxers. Rocky III disproved this adage—the brain was first. The heart followed in Rocky IV. Nevertheless, this entry had strong legs at the box office, capitalizing on the popularity of pro wrestling and MTV-style fare. Despite its success, the bar was now set too high for Stallone to envision a greater foe for Rocky V, stating that any continuation required resetting the series back to Rocky’s humble Philadelphia roots. Rocky emerged victorious at the box office but could no longer rely on the underdog formula to do it again.

- The 35th-anniversary director’s cut, Rocky IV: Rocky vs. Drago, provides more opportunities for Apollo to shine, gives Drago additional dialogue and expressive vulnerability, significantly reduces Nielsen’s role, and eliminates unnecessary goofiness, including the silly robot.

Qwipster’s rating: C+

MPAA Rated: PG for violence and language

Running Time: 91 min.

Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Dolph Lundgren, Carl Weathers, Burt Young, Talia Shire, Tony Burton, Brigitte Nielsen

Director: Sylvester Stallone

Screenplay: Sylvester Stallone