Super Mario Bros. (1993)

Since debuting in the video game “Donkey Kong” in 1981, Mario had become a celebrity, emblazoned on lunch boxes, pajamas, underwear, bedsheets, and starring in a couple of kids’ TV shows. Polls proclaimed Mario the current generation’s cultural icon, more recognizable to kids than Mickey Mouse. A bidding war erupted in 1990 for movie rights, which Nintendo would sell to the studio that could concoct a story from a game with minimal characterizations and story elements.

During this time, producer Roland Joffe, the Oscar-nominated director of The Killing Fields and The Mission, was seeking properties with a broad commercial appeal for his film company, Lightmotive. Watching his teenage son obsessed with the game, he knew a film adaptation could be an across-the-board hit. While big studios petitioned up to $10 million with Nintendo of America with animated film ideas, Joffe flew to Nintendo’s main headquarters in Japan, where he presented an outline to president Hiroshi Yamauchi for a live-action feature where the Mario brothers venture into an underground fantasy realm to save a captive princess. Nintendo liked Joffe’s approach granting Joffe and his Canadian producing partner Jake Eberts of Allied Filmmakers the film rights for $2 million, plus the retention of all related merchandising.

The next challenge was putting the game’s elements into a cohesive storyline. Joffe traveled to Kyoto to meet the game’s creator, Shigeru Miyamoto. Miyamoto revealed that the inspiration for Mario’s name and likeness was based on the landlord for the company’s office in New York who gets plugged into a mishmash of elements from Japanese folklore. Miyamoto didn’t expect the movie needed to be a carbon copy of the game, so long as it captured its fun, colorful nature and similarly appealed to all kids, teens, and adults with equal measure.

Top on the list to play Mario was Dustin Hoffman. Coincidentally, Hoffman, whose children were major fans of the game, had previously tried to acquire the film rights on his own to star in with Danny DeVito for Barry Levinson to direct. Hoffman, hot off of Levinson’s Rain Man, recommended its screenwriter Barry Morrow. However, once things seemed to be solidifying, Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa proclaimed Hoffman as the wrong choice. He much preferred Danny DeVito as the star. Eberts courted Penny Marshall to direct, but DeVito seemed more inclined to play Mario if he could direct. While DeVito awaited Morrow’s script before signing on, he allowed his name to be associated with the film to lure other talents. DeVito’s Twins co-star Arnold Schwarzenegger was offered the role of King Koopa, as was Michael Keaton. Both turned it down.

Hired for his affinity for heartfelt stories about brothers, Barry Morrow played the game about a day to concoct a basic throughline. He determined he would make a prequel explaining how the Mario Brothers earned their “Super” moniker, though his unfamiliarity with the game and his realization that most Mario adventures end in his own death had him struggling for a better narrative. Morrow crafted a road-trip premise with Laurel-and-Hardy protagonists, Mario the headstrong older brother and Luigi the innocent, naive younger brother assistant in their plumbing business embarking on a quest introducing the game’s elements. The production office found this premise so similar to Rain Man, they jokingly referred to it as Drain Man. Eberts pulled Morrow before he completed his first draft because his take felt too dramatic and serious and dwelled on the romance between Mario and the Princess in a way that was not going to entertain kids. Besides, Nintendo had already been involved in a Rain Man carbon copy, 1989’s The Wizard. Danny DeVito passed and TriStar departed, making way for Disney’s Hollywood Pictures who wanted Tom Hanks to star. Nintendo disagreed with paying him $5 million for someone with a spotty box office track record.

License to Drive‘s Greg Beeman was the first director signed. Beeman conceived of an alternate dimension akin to sword-and-sorcery films aimed at a younger set. However, distributors wouldn’t finance a full fantasy flick from an unproven director. After the producers were underwhelmed after screening an early cut of Beeman’s Mom and Dad Save the World, they decided he wasn’t the right fit and they split ways. Looking through a host of other potential directors, they soon targeted Harold Ramis. Ramis loved the game, but wasn’t sold on the film’s current concept and passed.

Meanwhile, they hired the screenwriting team of Jim Jennewein and Tom Parker to add the fun and color of Nintendo. The screenwriters fell in love with the game and repurposed its cartoony mythology into a Wizard of Oz-like fantasy with Princess Bride comedic flair, with the plumbers entering a large pipe into a fantasy dimension. They concentrated on the siblings separating physically and emotionally, reunifying through their rescue of Princess Hildy from her marriage with King Koopa, a dragon-like figure who has usurped the Crown of Invincibility. The script was well regarded by the producers and Nintendo.

Thinking of directors who could handle humor with a defined artistic aesthetic, Joffe recalled the TV show “Max Headroom”. He flew to Rome to meet its cutting-edge creators, British power couple Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, to craft Mario’s unique world with artistic flair. Their only prior feature was 1988’s thriller D.O.A. but had extensive music video and commercial experience. Included among scripts sent by their talent agency was Super Mario Bros. They despised the Jennewein/Parker script but they accepted because they thought they could turn the concept into a pop culture phenomenon like 1989’s Batman, with comic-book visual style. They envisioned the film as a prequel that inspired the Japanese to create a loopy, cartoony game.

Morton and Jankel wanted a more sci-fi and less fantasy approach, conjuring a scenario explaining that a meteor struck Earth 65 million years ago at the spot where Brooklyn is today, pushing a population of dinosaurs into a subdimension where they eventually also evolved into a human-like race. An underground portal that connects the dimensions is unearthed, with orphaned brothers Mario and Luigi finding the modern reptilian realm.

The directors hired Mystery Date‘s Parker Bennett and Terry Runte, intrigued with their mockup poster showing a maze of pipes leading to sinister eyes glowing in the darkness. Over several drafts, Bennett and Runte replaced childlike fantasy elements with rational science fiction the directors preferred. Eventually, they skewed toward a darkly zany romp like Ghostbusters, writing Mario’s part with fellow smart-alecky Chicagoan Bill Murray in mind (they suggested Bruno Kirby and John Leguizamo as Mario and Luigi). They renamed Princess Hildy to Daisy (one of the game’s two princesses), making her an orphan baby smuggled from the dino dimension, Dinohattan, into a New York convent. They decided that gamers needed more tie-ins, so they shoehorned over a hundred game elements into the story. The producers, worried about how the script’s escalating scope would blow up the budget, ordered rewrites to add more scenes in real-world Brooklyn, including rival plumbing operation, the Scapellis, and a major excavation premise.

Morton and Jenkel’s talent agency recommended Bob Hoskins for his working-class everyman qualities. Hoskins resisted for months, wanting to avoid permanent pigeonholing into kids’ flicks after Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Hook. However, $2 million and the chance to act opposite Dennis Hopper, were too much to refuse. Hoskins was unaware the film was based on a video game, while his kids wondered why their dad, who couldn’t even program a VCR, was chosen as the consumer electronics icon of their generation.

The directors ordered the script to capitalize on Hoskins’ dramatic range, hiring the screenwriting team of Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, specialists in exploring strong sibling character relationships. Clement and La Frenais delved into Luigi’s resentment of Mario’s surrogate parenting while replacing smart-alecky humor with satirical takes on action flicks, including a Die Hard-esque explosive Brooklyn Bridge climax. The final scene had the Marios approached by Japanese executives wanting to turn their adventures into a video game.

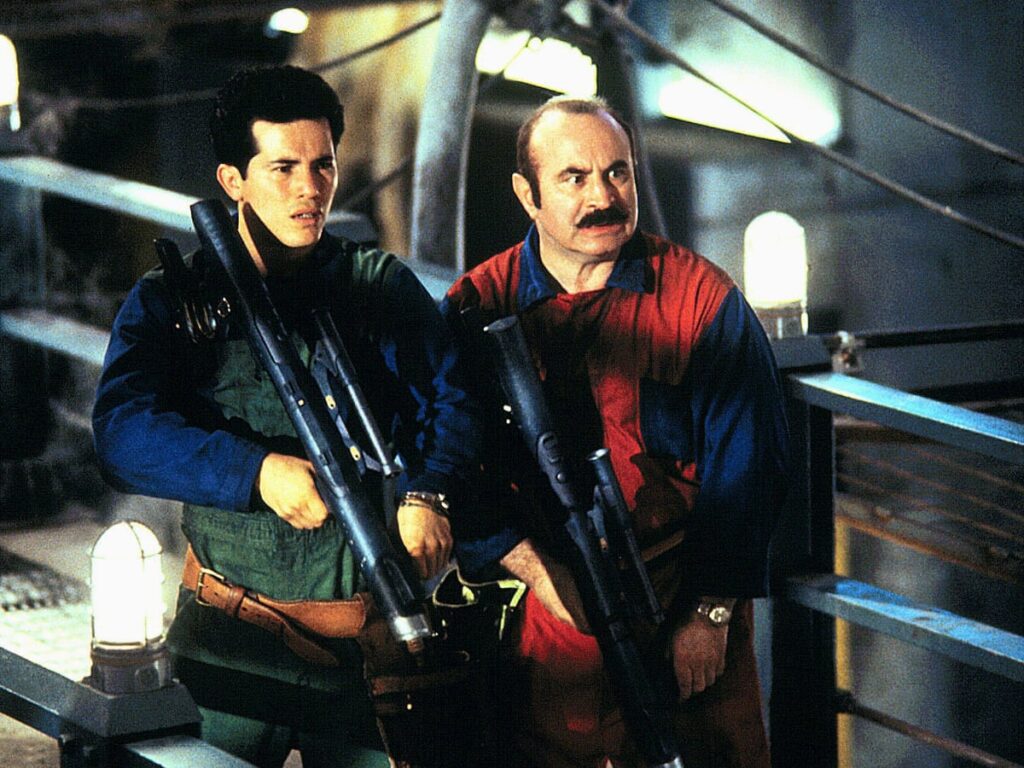

This appealing script lured in talent like Dennis Hopper and Fiona Shaw. Many actors for Luigi but the directors considered Bennett’s suggestion of John Leguizamo. They saw him perform “Mambo Mouth” in Chicago and found him hilarious and authentic. To play Luigi, Leguizamo passed on joining the TV skit comedy show “In Living Color” and launching his own sitcom. He also turned down the role of Tom Hanks’ lover in Philadelphia (Hanks wasn’t cute enough, he says; they cast the role with Antonio Banderas). Leguizamo and Hoskins, rehearsed their Brooklyn accent together to sound like they came from the same place.

After creative differences, they replaced Wolf Kroeger as the set designer with Blade Runner‘s David L. Snyder. Kroeger had followed the video game’s aesthetic but Snyder followed his own instinct based on what was possible with the locations they had. He gave Dinohattan a cyberpunk aesthetic the directors admired – New York if observed while on mind-altering drugs. The directors wanted a somewhat monochromatic look to Dinohattan with blues and reds.

Snyder toured deserted American mills and factories to cheaply provide the set structures necessary. Co-producer Fred Caruso worked in North Carolina for Dino De Laurentiis and introduced Joffe to the defunct five-story Ideal Cement Co. plant in Castle Hayne. Its New Brutalism style resembled an Aztec temple, providing ample space for effects labs and prop making. Snyder used existing concrete structures and catwalks for hanging scenery on multiple levels, with the ground level comprised of Koopa Square. On the downside, the facility had poor ventilation, airborne industrial dust, and no suppression of the high heat and humidity. Hundreds of extras played city residents. Many shops and streets are allusions to game elements. Snyder tried to base Dinohattan on the mythic Gershwinesque view of New York through the Japanese perspective. Due to the water shortage, Snyder designed Brooklyn as green and lush while Dinohattan is devoid of vegetation, an arid place where only lizards could feel comfortable.

For the game’s mushroom element, the directors and writers brainstormed a backstory of an old king deposed by Koopa devolving into a conscious fungus that spread throughout Dinohatten. The movie’s fungus used a fishing lure as its base and hot glue for its body consistency, with bread mold as its model. Many in the crew, sick of pinning fungus all over the set, hoped Joffe would stop it but he was trying not to ghost-direct at this stage. The directors also brought in “Max Headroom” co-creator George Stone to contribute additional ideas as the writers determined they needed to break off from the directors to form a story from what they had.

Expensive set-pieces forced them to acquire funding through a pre-sale to Disney, who demanded a child-friendly script revision because they wanted to build a Mario Bros’ related theme park attraction. Joffe contemplated writing a new screenplay himself but the directors begged him not to because they finally had a script everyone seemed happy with. Without knowledge of the directors, Joffe hired Bill & Ted co-creator Ed Solomon, along with Ryan Rowe to soften things without changing the plot because the sets and costumes were nearly complete. Solomon altered or excised adult elements like strippers, hookers, or junkies while jettisoning expensive set pieces like a Mad Max-style “Mario Kart” sequence and the Brooklyn Bridge finale. The directors were handed Solomon’s script two weeks prior to filming. They considered quitting but felt professionally obligated to carry through their complex ideas and felt they might save the film by making adjustments while shooting. Morton ceremoniously burned his meticulous storyboards in the parking lot because they no longer had relevance. Morton woke up early each morning to draft new storyboards for various units shooting concurrently. To retain the cast and crew, the directors promoted the changes they hated as beneficial.

After falling behind dramatically, the producers contemplated firing the directors, but no one else fully knew what movie they were trying to make. They fired the directors handpicked cinematographer Peter Levy instead to send a warning shot, replaced by Oscar-winning cinematographer Dean Semler. Semler questioned why he was hired when handed specific shooting, lighting, and lensing instructions. The eight-foot-tall Goombas, dino-humans devolved to reptilian form to be dumb enough to stay loyal to Koopa, were originally intended to make a tiny appearance, but they turned out so nicely that their appearance was greatly expanded. 35 technicians built the animatronic dinosaur Yoshi, requiring nine puppeteers controlling its 70 distinct cables to perform 64 movements.

Frequent script changes left everyone unprepared. The crew jokingly called the ever-changing production a “mutation” like the fungus, using the devolution chamber for each revision. Hopper yelled at the directors for changing lengthy speeches he’d rehearsed for weeks without consultation, calling them control freaks who valued no one else’s input despite being out of synch. The constant tirades further delayed the production, so the directors began encouraging improvisation. The directors felt the film was salvageable but not on the fly. After Solomon handled additional revisions at the request of the directors, he departed, Runte and Bennett were visiting the set and re-hired to perform mid-production rewrites. Joffe hired them on to revise, mostly as a hatchet job to remove costly elements from the script because the production had been going vastly over budget.

Fisher Stevens and Richard Edlund, who play Spike and Iggy, loved inventing zany dialogue, including an unused rap number. Their characters were scripted to devolve into Goombas but they convinced the directors that they should evolve to be super smart and realize they’ve been manipulated by Koopa and ally with the Marios. Meanwhile, Hoskins and Leguizamo binged scotch and weed to cope with the troubled production. Leguizamo’s intoxication during a driving stunt resulted in the Mario van’s sliding door slamming on Hoskins, breaking his finger; Hoskins’s cast is visible in several scenes. A stumbling Leguizamo later sprained his ankle, making him unavailable for two days.

Leguizamo romanced Samantha Mathis during the shoot, despite her dating Nicolas Cage at the time. Leguizamo bought a Siberian Husky puppy during the shoot, naming him “Luigi.” Luigi ate expensive earrings Leguizamo bought for Mathis. Leguizamo gave the dog laxatives until he got them back. It was all for naught; she dated River Phoenix while making The Thing Called Love during reshoots. Stevens had a dalliance with 17-year-old film extra Jamie Golightly. He and girlfriend Michelle Pfeiffer, who visited the set on occasion, split soon afterward Fisher cites his reticence to commit, Pfeiffer’s rising stardom, and their bi-coastal distance as factors. Meanwhile, a clean and sober Hopper bought a five-story sandstone Masonic temple in Wilmington to turn into an art studio and acting school. Lance Henriksen met his future wife, makeup artist Jane Pollack, during his one-day shoot in post-production playing Daisy’s father, the Fungus King back in human form.

Hopper called the directors’ decision to skip press interviews the first intelligent one they’d made. Hopper referred to the producers and studios intervening “the Hydra”; they originally had two heads telling them what to do, then four, then eight. Everyone had a vision but no one had control. After their allotted ten weeks, the producers ordered several more weeks of second unit direction done by Semler, Joffe, and others.

During the editing phase, the producers shut out the directors until the DGA demanded their reinstatement. However, the directors wanted to edit digitally but could only do it on film, so they were frustrated by how long it took, so the producers mostly had their way in the end. Test screenings drew poor marks for its hard-to-follow story. The producers had Runte and Bennett write a prologue on a rudimentary digitized animated intro, and several teams performed second-unit sequences, plus loads of additional ADR looping to make the pieces fit. Previews for critics were canceled after poor response internally. Bennett’s mother attended a preview and proclaimed it the worst movie she’d ever seen. Nintendo considered buying it out and shelving it but determined it was better financially to let it die in theaters.

Super Mario Bros. debuted in fourth place and fell from the top ten by week three, grossing $20 million. In Japan, Buddhist monks prayed in vain for the film’s success but it fared little better. The paycheck that brought many onboard proved not to be worth it; many found it harder to get gigs. Morton and Jankel were dumped by their talent agency returning to commercials until Jankel’s 2018 romantic drama Tell It to the Bees. Creator Miyamoto calls it fun but shoehorning in the game’s elements hurt the storytelling. Jake Eberts said he was the wrong man to bring “Super Mario” to the big screen and it remained his biggest regret in his career. Hoskins called Super Mario Bros. the worst thing he ever did and that the idiot directors had arrogance masquerading as talent. Hopper’s three-year-old son loved the movie but asked why he played the evil lizard. Hopper replied that it was to buy him shoes; his son said he didn’t need shoes that badly.

Super Mario Bros. expands the game’s surreal world but lacks a quality story. Trademark characters scarcely resemble their pixelated counterparts in appearance or spirit. For most viewers, playing the Mario video games for 30 seconds provides more entertainment than the totality of this 104-minute film. However, it has gained a small cult following for its sheer bizarre, deconstructionist qualities. Solomon compared the effect of watching the film to a kaleidoscope: the fragments don’t form a complete picture but the colorful elements still make it interesting to observe.

- A fan-restored and edited extended cut called “The Morton-Jankel Cut” intersperses footage discovered on a pre-release working copy VHS tape that surfaced on eBay in 2019. It can be found online.

- In 2012, a fanfiction webcomic sequel was made with Bennett

- In 2014, Super Mario animated film to producer Ari Arad

- In 2018, Universal and Illumination Entertainment are joining forces with Nintendo on an animated “Mario” film to be released in December 2022

Qwipster’s rating: D-

MPAA Rated: PG for violence

Running time: 104 min.

ice)

Cast: Bob Hoskins, John Leguizamo, Dennis Hopper, Samantha Mathis, Fiona Shaw, Fisher Stevens, Richard Edson

Director: Annabel Jenkel, Rocky Morton

Screenplay: Parker Bennett, Terry Runte, Ed Solomon