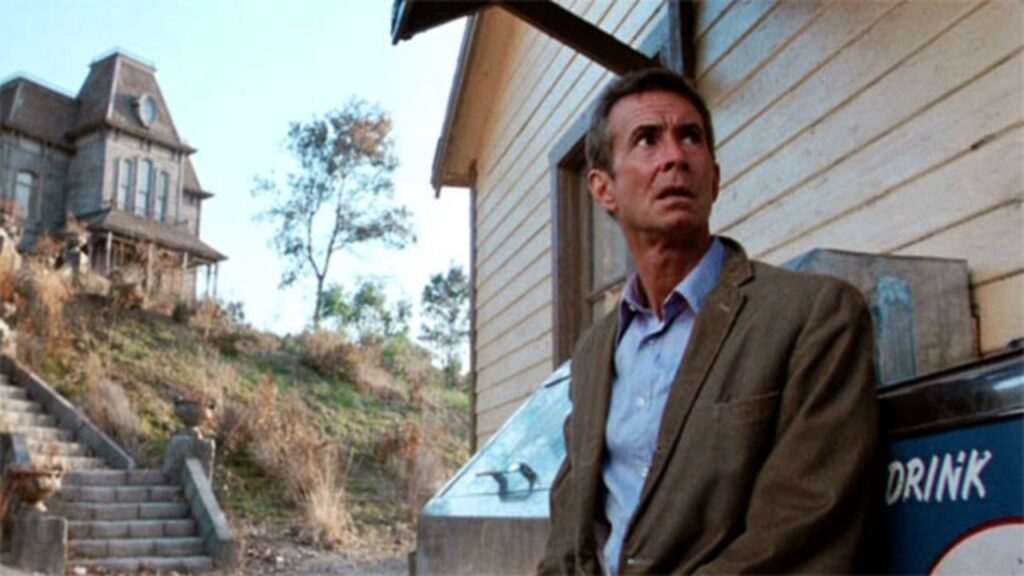

Psycho III (1986)

In August 1984, Universal greenlit the next entry in the Psycho franchise, Psycho III. Psycho II director Richard Franklin and screenwriter Tom Holland declined to return, causing Universal chairman Frank Price to hire Charles Edward Pogue, a promising screenwriter who’d impressed with his script for the remake of The Fly, to develop a story idea.

Pogue revisited Hitchcock’s Psycho, a film he’d seen before but vaguely remembered. His second watch made him a fan. Pogue found Psycho to be a rich, textured, and undeniably great film. Pogue next watched Richard Franklin’s 1983 sequel, Psycho II. He judged it above average for a sequel but disliked its sleazy slasher theatrics and its tampering with Psycho‘s mythology by suggesting the domineering woman who raised and engaged in an incestuous relationship with Norman that drove him to jealous murder wasn’t Norman’s real mother. Instead, Mother is now Emma Spool, a complete stranger working with Norman at a diner who’d given him up as a baby to her sister after going into an asylum.

A week later, Pogue pitched Universal two ideas. One would return Janet Leigh to the series. Leigh would play a psychiatrist who takes over observing Norman’s transition to society for the deceased Dr. Raymond from Psycho II. Her uncanny resemblance to Psycho‘s Marion Crane triggers Norman’s amorous feelings, and Mother’s homicidal tendencies. If Leigh declined, the character would be a runaway nun resembling a younger Marion as she appeared in Psycho, who connects with Norman as a fellow repressed soul.

Universal execs dismissed Leigh as too old to appeal to modern horror fans. A young wayward nun better provided Norman with someone he had the capacity to love, a woman as broken and insecure about herself as he is. Universal felt that audiences would feel tragedy when Norman kills her, which meant Pogue had to change his proposed ending revealing the killer was the motel’s assistant manager who was neurotically obsessed with Norman and the motel murders. Pogue was hired to complete a script, structuring it with Norman as the killer, including, tragically, murdering the nun he loves. The nun’s death forces Norman to confront Mother, figuratively killing her. Norman is physically captured but his mind is finally freed.

Pogue’s intent was to recapture the same tone, mood, and psychology of Hitchcock’s masterwork, avoiding the gorier, bloodier kills typical of modern slashers. Audiences should be frightened by what they don’t see, as in one of Pogue’s favorite horror films, the 1942 version of Cat People. Class, not crass.

Pogue sets the story three weeks after the events of Psycho II. Norman hires rogue musician Duane Duke as his temporary assistant. There’s a new patron staying in cabin #1, a spiritually faltering nun with an uncanny resemblance to Marion Crane, Maureen Coyle. Feelings of attraction are mutual between Norman and Maureen, but with jealous Mother controlling Norman’s homicidal impulses, that doesn’t bode well for her longevity. Meanwhile, tenacious reporter Tracy Venable comes looking for the whereabouts of Emma Spool from Psycho II, and she’s sure Norman is hiding something.

One hiccup: Anthony Perkins was miffed with Universal because they’d never paid him what they owed him after talking him down from his salary for Psycho II to accept a percentage deal. Universal paid him what he asked for and made several offers if he’d return for Psycho III, but he wouldn’t budge, not without approving the finished script because he found this unknown screenwriter’s idea of Norman romancing a suicidal nun beyond absurd. Universal told Pogue his script needed to hook Perkins or his part might have to be rewritten to be Norman’s nephew.

Luckily, Perkins loved Pogue’s completed script. It was beautifully written, tightly plotted, with inspiring strength and eloquence. Perkins made universal a counter-offer – he wanted to be Psycho III‘s director. Perkins’ thirst for directing came after friend Richard Benjamin convinced MGM to let him helm My Favorite Year in 1982 because he had an affinity with the material no one else possessed. Although Universal previously Perkins’s offer to direct Psycho II because Franklin already had the gig, Psycho III had no attached director. The time to push for the director’s chair was now or never.

Perkins told Universal he’d direct “F.O.C” – free of charge above his acting fee. Universal felt they had little choice, accepting on the condition that Perkins remain on schedule, under budget, and allow them not fight their creative control, or he’d be removed from the director’s chair.

Perkins had experience directing stage plays, He could handle actors but knew little about the technical side of filmmaking. He decided to play it safe and shoot as straightforwardly as possible, avoiding unnecessary, unflattering comparisons to Hitchcock. With Psycho, Hitchcock benefited from working with a blank canvas. The best Perkins could do is add shade and color to what existed before.

Perkins purchased several books on film directing. Most were too technical, but his favorite offered philosophy on how the director’s energy while making the film often sets the tempo for the energy that’s on screen. Perkins determined to direct as if he was having the time of his life. He also opted to surround himself with filmmaking veterans that would help him solve inevitable problems.

Hilton Green, first assistant director on Psycho and line producer on Psycho II, returned because Perkins desired less gore and blood than Psycho II. Green suggested hiring the Oscar-winning production designer who worked with him and Hitchcock on several films, Henry Bumstead. Universal offered Clint Eastwood’s favorite cinematographer, Bruce Surtees. Universal shot down Perkins’ suggestion of filming in black-and-white, something they also denied for Psycho II. If Perkins must shoot in color, he wanted it to look black and white, asking Surtees to capture a film noir vibe akin to the Coen Brothers’ Blood Simple, which they screened for the cast and crew several times to keep everyone on the same page. Perkins learned from Hitchcock to storyboarding the script in advance, hiring veteran artist Gene Johnson.

Perkins connected artistically with Pogue, a former stage actor himself, but wanted alterations to the script. Maureen’s journey from the convent to the motel would now open the film, similar to Marion’s journey in Psycho. They argued over the manner of Maureen’s death. In Pogue’s script, Norman kisses Maureen and then stabs her. Perkins insisted that Norman would never knowingly kill an innocent in his real persona. When Pogue countered that Norman couldn’t distinguish himself from Mother anymore, Perkins assured him that audiences wouldn’t accept such a character departure. If Maureen’s death must come at Norman’s hands, it had to be an accident. They paid homage to Arbogast’s death in Psycho by having Maureen tumble down the stairs, poetically getting impaled on the Cupid sculpture, symbolizing love as death in the Bates residence.

Diana Scarwid was hired for Maureen Coyle. Scarwid wasn’t a horror fan. She had a restless night following reading Pogue’s script. However, she accepted the role because her character wasn’t involved in the scariest, goriest scenes and she wouldn’t have to perform nude; her body double was scream queen Brinke Stevens. Scarwid saw Psycho III beyond its horror; it was a psychological study of people in pain and their inability to fit happily into a world of normalcy. Scarwid felt Pogue was exploring themes regarding the lightness and darkness in our minds, and how the walls we create to protect ourselves threaten to destroy our humanity. Maureen and Norman are orphans tormented by fatal mistakes of the past who find peace with someone who understands their sadness and sensitivity.

Perkins viewed the saga of Norman Bates as part of American homespun folklore – the dark side of a Norman Rockwell painting. The Psycho films are tragedies, not horror because Norman’s crimes come from love, not hate. Audiences sympathize because Norman would find happiness if others stopped provoking him in ways that stoke his impulses.

Roberta Maxwell plays investigative reporter Tracy Venable, looking to expose Norman for Mrs. Spool’s disappearance. Perkins liked Maxwell, a Canadian actor who performed with him on Broadway in “Equus” ten years prior. Perkins auditioned younger actresses at Universal’s request, but stuck with Maxwell, rationalizing that her age increased her desperation for a hot scoop to boost her languishing career.

Virginia Gregg returns to voice mother for the third time. Gregg commended Perkins for his direction, giving Mother nuance. Rather than bullying Norman, this version of Mother knows her power over him, needling him to do her bidding. Norman finds the strength in love to finally fight back.

To evoke the Psycho shower scene’s vulnerability, Pogue concocted similarly vulnerable murder sequences involving a bathtub, a phone booth, and a toilet.

As romantic release counterprogramming, the release date was scheduled for Valentine’s Day, 1986.

Universal wanted a book adaptation but “Psycho” author Robert Bloch retained literary rights to the characters. Bloch declined. He’d already done a book called “Psycho II” unrelated to the films, so writing a “Psycho III” unrelated to the books seemed counterintuitive, especially since had plans for another book, published in 1990 as “Psycho House”.

Perkins used his stand-in, Kurt Paul, to play Norman in rehearsals to see how scenes played. Whereas Perkins turned Norman’s persona on and off effortlessly, Paul had difficulty transitioning. He also irked the other actors by persistently bragging about his importance and close connection with Perkins.

Perkins called directing analogous to wrestling a dragon with 100 heads, but he never let on that he was in over his head. According to the cast and crew, Perkins’ was a thinker, listener, sensitive gentleman, generous collaborator, a paternal figure, complimentary and encouraging, looking to help everyone be their best. The only person he confided his anxieties to was Bruce Surtees, usually when someone was falling short in their performances. He wanted to project positive vibes to achieve positive results. He answered fan mail and sent autographs. When the Universal trams arrived during the filming, he had everyone wave, because each butt in a tram seat might become a butt in a theater seat.

Although Universal offered a slew of well-known composers, for the Psycho III score, Perkins looked to Blood Simple again, Carter Burwell. Burwell was pleasantly surprised, not only because he was a fan of Perkins but because he’s reluctantly returned to do his day job, computer animation work. It was Burwell’s first work for a Hollywood studio and resurrected his career as a film composer that continues today. Perkins told Burwell his score need not resemble the first two and to do his own thing. Burwell was granted the use of a Synclavier to sample tones and sounds. He eschewed sampling real instruments but incorporated vocal elements from Japanese Noh productions to evoke a strange, haunting feeling to the music, which he combined with an all-female and all-boys choir to give a disorienting effect. The only change Perkins requested was for the musical cues used in scenes involving Norman and Maureen, which he deemed overly schmaltzy and might make audiences unintentionally laugh. Burwell suggested that Perkins, who released pop albums in the 1950s, should sing while playing the piano. Perkins felt insecure about his voice, and even his piano playing, which he had dubbed over by Burwell.

In addition to the score, Universal wanted a pop song attached to make a music video that would promote the movie. Perkins wanted the song to connect with the movie and incorporate Burwell’s composed theme. Burwell collaborated with several rock artists. Perkins nixed adding lyrics from Wall of Voodoo’s Stan Ridgway over the main theme because the words didn’t jibe with the portrayal of Norman he wanted to project. Universal canceled one by Oingo Boingo’s Danny Elfman, a burgeoning film composer in his own right. Elfman and Burwell made a song in rhythm with a slowed-down version of Bernard Herrman’s shrieking, shower-scene violins from the original Psycho. Eventually, Burwell decided to resurrect the instrumental track he created with Steve Bray and David Sanborn for the gutted sex scene and call it, “Scream of Love”. Though it lacked crossover appeal, Universal had Arthur Baker do a 12″ dance mix and shoot a promotional music video, which played on MTV on Halloween when Perkins was a guest VJ.

Universal was high on Psycho III‘s prospects but wanted to up the commercial appeal. They wanted Perkins to reduce the sexuality, add more blood, and give the ending a shock twist. Perkins wanted to emulate Hitchcock by never showing a knife entering a body (at least until Norman takes on Mother) and avoiding blood splatter. Not that Perkins was averse to blood. He enjoyed playing up a scene of Sheriff Hunt reaching into the motel’s ice machine where Norman has stuffed a victim to suck on the ice. Perkins requested actor Hugh Gillin to pop some bloody ice into his mouth for one take. Gillin protested it as juvenile, but Perkins encouraged him to do it anyway, stating that he likely wouldn’t use it, but he added it in the final cut.

Universal was worried that audiences, particularly teenagers, would be disappointed that they paid for a horror movie and didn’t get the gory details when the murders occur. Perkins acquiesced to the studio’s demands to reshoot the murders with more graphic viscera. But he wanted it to be quick because he didn’t want audiences cheering on Norman’s tragic relapse into murder. The release date was postponed from Valentine’s Day to the July 4 weekend for reshoots, prime real estate that suggested that Universal had high expectations for a huge success once the changes were made. So high were they on the film’s prospects that they ordered Perkins and Pogue to come up with an idea for Psycho IV.

Perkins reshot the toilet murder involving actress Katt Shea with makeup artist Mike Westmore rigging a neck device that opened a slit in Shea’s neck that gushed blood. Universal also wanted more blood for a phone booth murder but wanted a sex scene between Duane Duke and the victim that precedes toned down, fearing adults wouldn’t bring their teenage kids to it. Perkins, who’d recently appeared in the kinky thriller, Crimes of Passion, argued that displays of sexuality would drive Norman mad, but agreed to a “less is more” approach. Due to discomfort with frontal nudity, it was Fahey’s idea to sit in a chair using lamps to obscure it.

Universal also wanted a “Brian De Palma” ending that left audiences shocked. Pogue’s original ending following Norman proclaiming he was finally free as he was caught by Sheriff Hunt for his crimes was a crane shot panning up to the Bates House through the open window overlooking the motel, revealing an empty rocking chair, symbolizing Mother is finally gone. Perkins and Pogue cycled through potential final shocks, including Norman killing one more time, either the sheriff, priest, or reporter. None seemed satisfying but the best idea had the camera follow Norman in the cop car revealing he possesses Mother’s severed mummified hand. Pogue hoped that Universal would realize its contradiction, not only to Norman’s proclamation of freedom but virtually everything leading up to it. Unfortunately, Universal seemed content with the twist.

Perkins was also asked to reshoot some underwater sequences in the climax because it was too dark and murky to see the identity of the bodies.

Universal sensed a potential runaway hit. It played at Cannes Film Festival, out of competition. Universal paid $10,000 a month for a 70-foot-tall sign at Times Square. Perkins traveled in person with advance screenings to get the public interested, handing out Bates Motel keyrings and personal autographs. There was also a USA Network contest for a weekend stay for two in the refurbished Cabin 1 of the Bates Motel on the Universal lot. The room had a working shower but the hole in the wall was patched up.

However, Universal’s attempts to play to the horror crowd backfired. Critics and audiences were mystified by its gratuitous violence and dark, moody tone, greeting Psycho III‘ with negative reviews and a poor box office performance. It debuted in eighth place before falling out of the top ten altogether, yielding only $14.5 million domestically. Its failure put the kibosh on the Pogue’s idea for Psycho IV, a black comedy premise where Norman escapes after the asylum conducting radical therapy techniques burns down, so Norman escaped with a mute girl in tow to the Bates Motel. The motel has been converted into a mystery theme attraction run by an eccentric entrepreneur, drawing in crowds looking to participate in re-enactments of the motel and Bates house murders. When the actor playing Norman Bates in the production quits, the real Norman steps into the role.

Perkins felt it could be the best film in the series, but the studio soured on its viability, especially with Perkins at the helm. Perkins subsequently fell into an emotional funk, apologizing to the cast and crew for working so hard on a film that deserved better than what he could deliver.

Although uneven, Perkins brings quality style and symbolism to the proceedings, paying occasional homage to Hitchcock, such as the opening scene in a California mission bell tower in which a nun falls to her death (Bumstead was the production designer on Vertigo). The homage to Psycho‘s shower sequence shocks and surprises, as Mother strikes the intended victim with hopefulness rather than horror.

Pogue’s script not adeptly follows its predecessors but introduces several interesting characters and surprisingly smart, darkly witty moments. Jeff Fahey excels at Duane Duke, the motel’s new clerk, sleazy but savvy, providing a worthy foil for Norman’s oft-naive ways, playing the devil to Diana Scarwig’s angel on the opposite side of Norman’s shoulders.

Like its immediate predecessor, Psycho III falls short of Hitchcock’s original in terms of ingeniousness and artistry, but Perkins has nothing to apologize for. A great script and robust direction from Perkins and Pogue are mostly undone by the studio’s commercial insistence to copycat horror trends and add distasteful elements that mar their attempts to recapture the class of the original, as well as depriving Norman of completing his arc to freedom through a gimmicky, dispiriting ending.

Qwipster’s rating: C+

MPAA Rated: R for strong, bloody violence, sexuality, nudity, and language

Length: 93 min.

Cast: Anthony Perkins, Diana Scarwid, Jeff Fahey, Roberta Maxwell, Hugh Gillin

Director: Anthony Perkins

Screenplay: Charles Edward Pogue