TRON (1982)

In the 1980s, Disney has been in the course of trying to find its footing yet again for the prominence it once held in the world of animation. This included pulling in talent from other spheres to try to stay innovative, and for their 1982 release, TRON (a shortening of the word, “electronic”), they brought aboard animator and video game enthusiast Steven Lisberger (Hot Pursuit, Slipstream), who had been working on the conception of the project for several years, inspired by the notion of people being trapped within the world of video games he had become addicted to (especially “Pong”), and producer Don Kushner (But I’m a Cheerleader, True True Lie) from the realm of computer animation, where the notions of the computer as an alternate reality proved popular. Lisberger’s original intent had been to make a traditionally animated film (with live-action scenes bookending it) on a much smaller budget for a 1981 release, but had trouble with the funding when another project he had been working on, Animalympics, didn’t pan out as expected. Disney still liked what they were coming up with, and, in 1980, hoping to expand their film demographic beyond young kids to appeal to teens and younger adults, bought the rights to their project and gave them over $20 million to play around with in making it to be released in the summer of 1982.

Kevin Flynn (Bridges, Cutter’s Way), video game programmer, is ripped off of several ideas by an unscrupulous power hungry man named Ed Dillinger (Warner, Time Bandits). Dillinger soon starts a meteoric rise to the top of a powerful global corporation, Encom, while the computer that runs it has become so powerful that it is a life-force unto itself, thinking and talking (not to mention plotting world domination). Flynn tries to hack into the computer to get evidence of Dillinger’s theft, when the Master Computer sucks Flynn into its own cyber-world, dubbed “the grid”, where programs in the voice and form of the programmers that created them are mere toys by which Master Computer uses for its own enjoyment.

An experience more of the sight than the mind. Truly gorgeous and mind-blowing special effects are the must-see highlight of this otherwise poorly scripted misfire from Disney. All the ingenuity went into creating the fantasy world of special effects, while none seem to have made its way into a script that has little in the way of humor, with sparse dialogue barely rising above the level of a typical comic book, despite dozens of extensive rewrites during the film’s development phase. On top of this, the film is very confusing, partially due to not being built up very well in terms of expository information that would keep viewers clued in as to what is going on from a motivation standpoint. Without a plot that most will be able to readily follow, without characters who do or say anything interesting, and without any other moments of enjoyment within the writing or direction that lead to excitement, the only thing that the makers of TRON can offer to sustain interest are those visuals. For some, that will be enough, but anyone looking for something more than a dazzling display will find little engaging for the duration.

As for the writing and direction by Stephen Lisberger, it’s conceptually brilliant in its fashion, but his work is nearly undone by the fact that his writing and directorial skills are not nearly up to the speed necessary to deliver on those high concepts. Lisberger certainly tries to some extent to imbue his film with the kind of evil vs. good confrontations that ran popular in the wake of Star Wars, which certainly is one of TRON‘s main influences, though others have cited that there are more than one or two similarities between TRON and 1960’s Spartacus. However, faulting Lisberger solely for the stiffness inherent in the finished product may not be warranted, as TRON was truly a groundbreaking endeavor in the realm of animation, and many who were working on the film, namely a slew of computer programmers new to the realm of big-budget Hollywood film-making, with all of the hustle and bustle in doing a lot with very little in time, only knew how to generate the visual effects intended, but did not know what worked or didn’t work from a compelling cinematic standpoint.

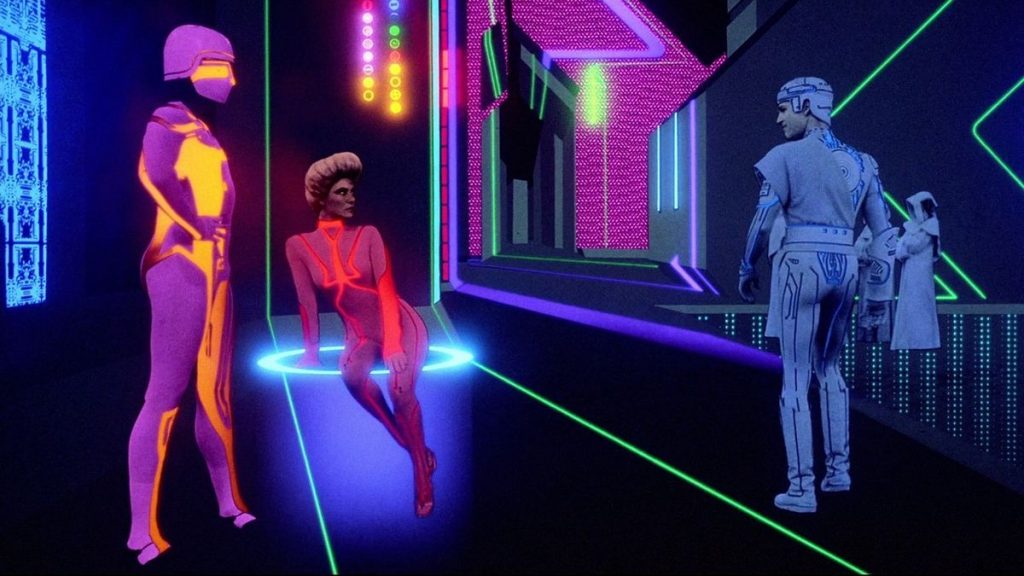

Though the film boasts a healthy budget, the cost of making the world within the cyber-scape fully computer animated would prove too expensive, requiring ways to bring in live-action actors and sets when possible, and to touch the film up with some traditional hand-drawn animation, also geometric in appearance to blend in, over backgrounds back-lit with computer designs (the spider-like gridbugs being the more obvious example). This, of course, means that those analog injections need to match with the digital, so the actors and the various sets and props needed to get that similar look of light, dark, and color scheme. Reportedly, the artist Jean Giraud, aka “Moebius”, worked on the original designs for the various characters and their costumes, which would earn the film one of its two Academy Award nominations (the other for its impressive sound work). The film’s virtual reality sequences were shot in black and white, with color digitally added to give it its hi-tech look.

Some feel that Disney allusions abound: The founder of the company, a man not-so-coincidentally-named Walter, who has taken a back seat to those who have usurped the company’s legacy for their own profits, telling him that the company is no longer the same one he created from his garage. Eventually that company is freed from its destructive corporatism by handing the controls back to the creators rather than the empty suits in charge, represented by Dillinger. This may make for an interesting read on the film, though perhaps too progressive at the time; the creators of the film were more of the mind that major tech corporations like IBM would gobble up (aka, “de-resolution”) all of the creators who emerged initially successful from their garage concepts, and that it would stifle ingenuity in favor of feeding the giant to become even larger. Still, the fact that Mickey Mouse’s head can be seen as part of the artwork that passes by during the solar sailor sequence does implant in the mind that those who were working on the film could see the parallels to their own existence working for the profit-over-all thinking within the company at the time.

The much-maligned Disney of this era had some difficulties in attracting acting talent to their films at this time, but Jeff Bridges signed on to the film due to his interest in the concepts presented, though TRON will likely not go down as one of his finer performances, as he does not perform well when trying to act in front of black screens, matted concept work, and painted black sets with no other definition, or with effects that haven’t yet been put into the film. Despite some good thespians in the bunch, none of the rest of the performers fare much better, many of them having difficulty in performing their roles without much movement, as the animation wasn’t advanced enough to add moving actors along with computer animation simulating motion.

David Warner, a fill-in for the originally intended Peter O’Toole (who, instead, wanted to play Tron, going so far as to try to convince the production team that he was still spry enough to handle the physical scenes, then passed on the film after learning about the black-screen/back-lighting effects concept that he couldn’t understand in the slightest), is a dull villain, while Bridges and Boxleitner (“The Scarecrow and Mrs. King”) can’t breathe any life into their laughably trite lines. Warner’s voice was also altered and used for the Master Control Program, even though Dillinger was not its original creator. Boxleitner initially had no interest in doing the film, but changed his mind once Bridges came on board and more of the concept boards had been drawn up as to what the movie would be trying to achieve visually. With such a surreal and breathtaking visuals, and a story-line falling somewhere between Metropolis and Wizard of Oz, this film could have been a great movie with a better writer/director than first-timer Lisberger. Fans of eye-candy will enjoy the film, but everyone else may fall asleep from the tedium. Cindy Morgan (Caddyshack) joined the film later after the producers toyed with the idea of casting Blondie’s Debbie Harry for the role of Lora, Alan’s girlfriend (and Flynn’s ex) who also works at Encom; Harry had also been sought after for the role of Pris in Blade Runner the same year.

Composer for The Shining, Wendy Carlos, developed a synthesized score that is consummately appropriate and memorable, keeping the story within the realm of the digital in its virtual soundscape. As the visuals use computers in order to give us a peek into the world of computers, so too does the sound stress the inorganic to match those very visuals.

For as much work as many put into the film, and even after Disney spent millions of dollars in promoting it, everyone involved new it was a gamble, as it had been an unprecedented undertaking in visual design that also relied on a concept to root audiences into seeing it. Video games being all the rage, and with Disney desiring to break out of their creative tailspin, they ended up feeling like the chance would prove worth it. They were kicking themselves on passing on Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark and didn’t want to see another potential blockbuster slip through their fingers (though there is some irony in knowing that they would eventually own the rights to the aforementioned Lucasfilm properties). Alas, it’s a concept whose time had not yet come, as TRON would end up a box office disappointment, making less than $30 million in its initial run, which barely covered the money they had already spent in terms of budget and advertising. It only made a quarter of what E.T. made in its fifth week of release in its debut, and fell out of the top ten after a meager three weeks.

An experience more of sight and sound than emotion, TRON isn’t a very compelling film beyond its concepts and design. Nevertheless, it has amassed and retained a considerable cult following over the years among those who feel it had been a film too conceptually different to be appreciated within its own time, and certainly there are elements of the movie that have become part of the science fiction film fabric over the years, with influences ranging from The Matrix to Ready Player One. While some old-guard animators at Disney refused to work on the film because they feared that computers would take over their roles, it would take over a decade before we would begin seeing full-length animated features done primarily with computers, with the coming of Pixar (John Lasseter has commented that his witnessing of the work on TRON while an animator at Disney planted the idea within his mind of where he wanted to go, artistically, He now heads Disney animation). The time and technology were right in the mid-1990s in a way it wasn’t in the early 1980s most Hollywood animation is done entirely with computers, showing how far the tree has blossomed from TRON‘s original seed.

— Followed in 2010 by TRON: Legacy, which brings back Jeff Bridges and Bruce Boxleitner in their iconic roles

Qwipster’s rating: C

MPAA Rated: PG for sci-fi action violence and brief mild language.

Running Time: 96 min.

Cast: Jeff Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner, David Warner, Cindy Morgan

Director: Steven Lisberger

Screenplay: Steven Lisberger