Sphere (1998)

Michael Crichton began writing “Sphere” in 1969 as a conceptual follow-up idea after his best-selling novel, “The Andromeda Strain”. He liked sci-fi stories where aliens wouldn’t resemble humans in any way. Whereas “The Andromeda Strain” had a physical threat to humans in the form of a deadly virus, his next intended story would reflect how an alien encounter affected humans on a purely psychological level, especially in our primal instinct for fear when encountering the unknown in extreme situations. What would we really do when confronted by our first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence or an object from an intergalactic civilization far more advanced than ours?

Crichton mused that if Charles Darwin in the 19th century sat in front of a Macintosh computer from today, even someone as rational and scientific as he would scream from the room, thinking it was surely witchcraft. You couldn’t begin to rationally explain it to him because all of the things that make a Macintosh run are also unknown to him. He would only perceive a weird rectangular object that displays images of unknown origin and meaning. If the most intellectual mind from 100 years ago couldn’t fathom something that exists today, surely our best scientists would have a similar experience if introduced to something invented 100 years from now.

As a writer, Crichton often had multiple projects going at once. He paused on stories when he was stuck, then returned when new ideas formed. Crichton had difficulty writing a story where the main object was beyond explanation to us in our time, so he put it aside. “Sphere” didn’t get fully formulated until the 1980s, after Crichton grew weary of seeing pie-in-the-sky optimism dominating science fiction in the works of Carl Sagan and Steven Spielberg, imagining contact with aliens as a wonderful thing. Crichton felt that, in reality, any alien contact would immediately trigger a fear response in humans, and our worst traits would come out rather than our best. Even leading scientists would be woefully unprepared, as there’s no honest training for alien encounters.

“Sphere” became a “what if’ premise, exploring how scientists might honestly react when confronted with a powerful and highly advanced object of alien origin. No matter how sophisticated and learned the scientists are, their reactions would be primitive – fear, paranoia, panic, and confusion. He imagined an alien artifact in the shape of a sphere, which had properties that would not be explained in the story, feeling that no human would be able to ever fully comprehend something of alien origin from a few hours of exposure. This sphere has a unique ability to manifest the thoughts and feelings of sentient beings around it, but those around it would instinctively project their own fears of it, resulting in a nightmarish reality built on their innermost thoughts, not dissimilar to Forbidden Planet, with its “Monster from the Id”, or in the novel of film adaptations of “Solaris”, where things are manifested from the subconscious thoughts of one of the characters.

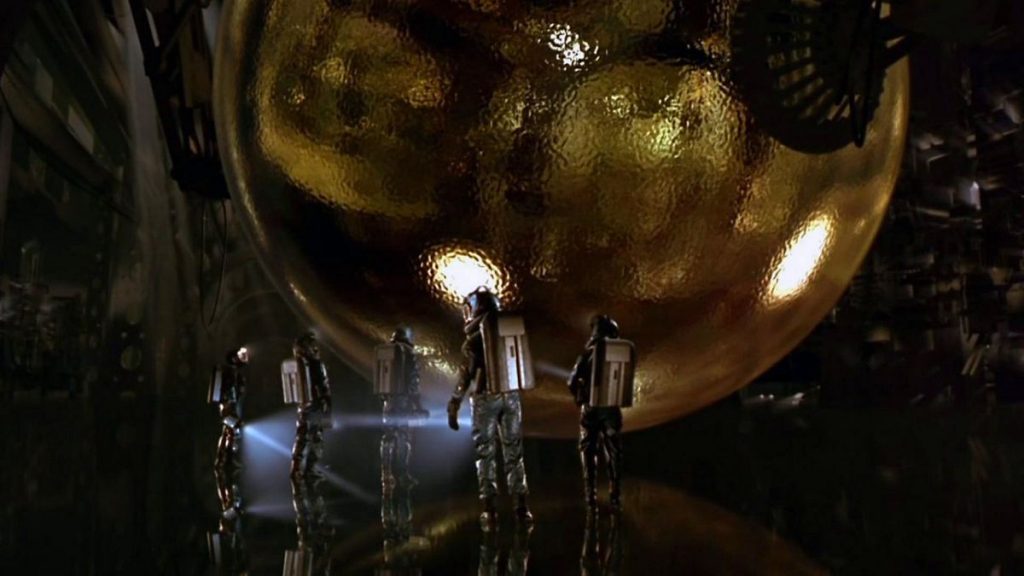

“Sphere”, as published in 1987, concerns a team of civilian American scientists sent to investigate a massive 300-year-old spaceship believed to be of alien origin half-buried in a bed of coral on the ocean floor 1000 feet below the surface of the South Pacific waters. Their secret mission leads them to the US Navy’s underwater habitat near the site. Inside the ship is an impenetrable silver sphere thirty feet in diameter of unknown origin that seems to influence the humans investigating it. Due to storms on the surface, the scientists have no choice but to confront the strange phenomena manifesting around them, phenomena created by their internal fears taking forms physical and deadly.

The book wasn’t a hot seller until Crichton’s back catalog experienced renewed interest after the success of “Jurassic Park”. In the wake of the film version of Jurassic Park‘s phenomenal success, movie studios began snatching up available Crichton properties. One included Warner Bros.’ adaptation of Crichton’s thriller, “Disclosure”, that went to director Barry Levinson in 1994. Levinson’s production team of Peter Giuliano and Andrew Wald were impressed with how well Disclosure had done and inquired about other Crichton properties they could adapt and discovered “Sphere” was available.

Despite heavy studio interest for several years, Crichton wasn’t keen on Hollywood adapting “Sphere” because he didn’t want see it degenerate into a poor effects-driven film. However, due to his good working relationship with Levinson on Disclosure, he acquiesced to releasing the rights to Warner Bros. Levinson hadn’t heard of “Sphere” but read Crichton’s novel while in pre-production on Sleepers and became very excited about the prospects. He had always wanted to do science fiction but hadn’t found a property he felt was in his wheelhouse, but Sphere was an exception. Levinson wasnt sure he could pull off some CG alien monster flick, but Sphere was more geared toward being primarily a psychological drama with a futuristic backdrop; he called it Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? of sci-fi.

Crichton told Levinson that, although he wrote the first draft of Disclosure, he wasn’t interested in adapting Sphere. He felt creatively drained trying to rewrite or direct from a story he wrote, calling the experience, “having the baby too many times”. Just the thought of having to take the first 150 pages of “Sphere” to squeeze into 30 minutes of screen time filled him with no pleasure. He’d accept a role as a producer, where he could make script suggestions, but outside of providing notes and entertaining story discussions, as a filmmaker himself, Crichton promised to avoid telling Levinson how to make his film. Crichton had full trust in Levinson in all capacities because he was a writer and had great story instincts.

Warner acquired a two prior adaptation attempts in the deal, including by Kurt Wimmer. Levinson felt they didn’t grab like the novel because they strayed from Crichton’s book and favored technological explanations over the characters. Levinson felt what happens to the characters psychologically was the real appeal, not the tech. Levinson also wanted a more faithful adaptation. Millions of Crichton fans would be disappointed if the film version differed substantially from the book. After Levinson’s assistant, Stephen Hauser, volunteered to lay out a new story treatment using Crichton’s novel and Wimmer’s script. Levinson liked it and told him to write a full draft. Afterward, Levinson hired Paul Attanasio, who created his acclaimed TV series, “Homicide”, to polish the dialogue and enhance characterizations.

Levinson is a meticulous planner who spends months in pre-production to assure a smooth shooting schedule. He found this necessary for Sphere because he’d never worked underwater and much research and testing of camera gear were needed to ensure adequate density and lighting. The camera crew needed to be adequately trained so that they knew what each scene required and downtime would be minimal. The crew and actors would undergo two weeks of training as required for the production to clear insurance requirements. Levinson said that preparation allows for more spontaneity rather than less. They can add scenes and experiment in more directions as they went along because the planning kept them ahead of schedule. Levinson didn’t storyboard scenes unless necessary so that the actors would feel the freedom to explore their performances and contribute things they hadn’t planned for that might strengthen the overall film.

Although Levinson regularly delivered films on time and under budget, recent water-based films like Waterworld, The Abyss, and Titanic had Warner gunshy about costs and delays escalating. Warner ch-chair and CEO Terry Semel wanted the fat trimmed from the budget, lowering the $85 million by $10 million and the shooting days from 90 to 70. In November 1996, pre-production paused as Warner determined how to achieve this and retool the script accordingly. CG would be used to replace costly practical effects, but they opted to replace Industrial Light and Magic with Jeff Okun and Tom Boland, who could assemble a quality team on site without the high overhead costs of ILM’s facility and staff operation. Levinson requested that, as they rejiggered thing for the leaner production, he would use the down time to shoot Wag the Dog in Jabuary 1997 with a 30-day schedule. Warneraccepted on condition Levinson return to complete Sphere before editing Wag the Dog.

As for the underwater action, an open sea shoot wouldn’t adequately control the elements. With Warners’ giant tank currently in use for Batman & Robin, the Pinewood studios tank not feasible, and the Malta tank a “floating tank” in the Mediterranean barely better than the open sea, they searched for a place to build their own tanks to control water clarity, filtration, and temperature. Adam Greenberg, the cinematographer who had collaborated with Levinson on Toys, lacked underwater experience but discovered a clever way to shoot in a container only 7 feet deep could appear as 2000. They secured Mare Island Naval Shipyard, a military base in Vallejo, CA, where nuclear submarines were constructed before closing in April of 1996. With ample space for building, parking, and strong local labor pool, plus its proximity to Napa Valley, the wine capital of the United States, it seemed an ideal choice for work and play.

Exterior underwater structures were done using 1/16 scale miniatures by Grant McCune Design. The internal habitat set was a continuous set, mostly enclosed to heighten the sense of claustrophobia for the actors, and so audiences perceived no escape or place to hide were possible, as the camera follows the actors through rooms without cuts. In addition to cramped conditions, the set proved difficult to light and didn’t dissipate heat well.

The water depth in the 40′ x 40′ tanks was kept to 26 feet by design so that divers wouldn’t have to expend time with decompression after surfacing (Navy consultants said diving less than 28 feet avoided the need to decompress), The’ tanks were built within three giant assembly warehouses, plus one in a different building to house the habitat. Levinson did not get into the water for efficiency of communication. He stayed in the video village and gave instructions as he looked from the monitors and could see exactly what the cameras were seeing. He could give directions into the helmets of anyone necessary to move to a different location or try different things.

Dustin Hoffman was the first actor signed. Hoffman enjoyed working with Levinson and habitually asked if he had any parts in upcoming projects for him. Hoffman would argue that “working with Levinson” was the wrong phrase; his experience with Levinson was so fun he considered it more play than work. The main character was a middle-aged man and was a psychologist rather than a man of action, so the part seemed tailor-made for Hoffman. Hoffman hadn’t heard of the Crichton novel but he accepted the role after hearing the story because he liked the underlying themes. Hoffman turned down the role of John Quincy Adams in Amistad to work again with Levinson for the fourth time for Sphere, though this did push the release date as Hoffman needed to complete work on Mad City for Warner first.

Levinson is also an actor and knows actors enjoy space to grow. Hoffman took notes while comparing the book to the script, over 80 pages worth of background information and lines from the book that weren’t in the script that could be used to enhance everyone’s performances. What Hoffman found most interesting from the book is the notion that we continue to spend lots more to explore space than we have Earth’s oceans, which represent most of our planet. We have no clue what might be down there, an alien craft had less of a chance fof being discovered buried at the bottom of the deepest part than approaching from outer space.

After Albert Brooks left for the Sidney Lumet drama, Critical Care, the astrophysicist role was cast with the SCUBA certified actor, Liev Schreiber. Schreiber wasn’t keen on a smaller role so he would improvise new lines to expand his screen time. Laura Dern, Charles Dance, Julian Sands, and Joe Mantegna were slotted for various roles but left due to production delays.

Samuel L. Jackson, no stranger to Crichton adaptations after Jurassic Park, was an early choice for Harry but he was too busy with The Long Kiss Goodnight to read the book. The role passed to Andre Braugher, a TV star in Levinson’s show “Homicide”. However, after the film’s postponement, Braugher left in February of 1997 because his wife, “Homicide” co-star Ami Brabson, was pregnant with their second child and he wanted to be with his family. Jackson, initially a marine biology major in college and a lifelong sci-fi fan, had expressed disappointment after reading and enjoying the novel that he’d been passed over and accepted immediately when learning he’d be working with Hoffman.

Jackson came straight to the set after completing work in Montreal on The Red Violin, where he played an antique dealer in his 60s. He had shaved the middle of his head for that part. Rather than wear a wig, which would have been a chore given all of the scenes in water, Jackson asked Levinson if he’d like him to completely shave his head. Levinson told him to do it to see and liked it well enough. Jackson especially liked the look because he felt it shaved 15 years of his age and he stayed with that look ever since. Jackson would become an avid scuba diver after his experience learning dive techniques in Sphere. For the last month of the Sphere shoot, Jackson would leave for Los Angeles for the weekend to begin shooting Jackie Brown.

After Sharon Stone pulled out of Oliver Stone’s U-Turn over a money dispute, she campaigned to appear in Sphere. She took to calling Levinson’s home, and even came over to his house to act out the role in his living room. She convinced Levinson, who was convinced the had the aggression and vulnerability necessary, as well as an intellectual, enigmatic personality. He worried that she seemed an unlikely pairing with Hoffman, but considered this might add an extra dimension of complexity in a teacher/student dynamic that went too far. Stone took the role after accepting a lower rate than her usual salary.

Despite being a SCUBA certified resue diver up to 80 feet, Stone underestimated the physical demands required, especially in feeling overwhelmed early in the shoot. She experienced claustrophobia and diffculty adjusting to the breathing methods in her diving sui, causing her to scream she wanted out. The crew fitted her with a jet propulsion device so she’d surface quickly when panic set in. The airlock set that filled and emptied with water caused a startling, sudden shift in pressure she found exceedingly unpleasant and refused multiple takes. Her bad vision kept her underwater visibility was limited. The National Enquirer reported an incident that Stone denied happened where she nearly drowned after slamming into the tank’s side wall, resulting in Jackson pulling her out and administering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Meanwhile, Hoffman was injured during a dive after hitting his head on an underwater camera that hadn’t moved away in time, requiring a hospital visit and 25 stitches just above his hairline. His swollen forehead required them to film only from the back of his head for a week.

Stone also thought her career depended on her always looking glamorous, requesting to be shot only from one side and never from below, especially in harsh light. However, cinematographer Greenburg needed harsher light due to the environs, which made her apprehensive.

Jackson was occasionally awe-struck, his mind drifting in self-reflection that he was acting with Hoffman. Hoffman would tease him mercilessly when this occurred. Hoffman and Stone improvised many of their scenes together. It was their idea for their characters to have a history together as doctors and patients who had a falling out over something Norman did. Levinson wanted to keep the incident ambiguous.

Levinson cast Coyote, who he’d met through social circles , as the military commander because had power in his intelligence. He thought he would be much more interesting in that role than a tough-as-nails military stereotype. Queen Latifah was also SCUBA certified. Her character was shot to have a much more gruesome moment after death when surrounded by a group of jellyfish. They had created a prosthetic head with swollen areas. Jellyfish would be still attached to her head; as they pulled the jellyfish off, the tentacles came out of her nostrils and eye sockets. Much of these was cut for being too gruesome. Also nixed was the use of slime excreted from the bodies of the hagfish that attacked Hoffman’s character.

Because the diving suits were about 140 lbs., lengthy delays to set up shots resulted in actors taking catnaps underwater rather surface to take off and put on all of that gear again, which took several people to do.

The sphere’s appearance, which was done entirely in CG, was a difficult consideration. Levinson imagined a giant ball-bearing, but without any door so it wouldn’t resemble a mechanical object so much as an artifact of mysterious properties and intent, much like the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s mystique came from reflecting everythig in the cargo bay except for the human characters observing it. Only when someone is inside does it show them on the surface.

Levinson told the effects team there shouldn’t be creatures except ones found in reality. These are the manifestations of mature scientists not children prone to flights of fancy. Audiences shouldn’t know if what they’re seeing is real or manifested. Even the main characters don’t know what’s real, or who they trust, or if they can even trust themselves.

The giant squid is only shown as a blob on a sonar screen. After watching other films featuring a major cephalopod, especially the TV movie for Peter Benchley’s The Beast, with its flailing tetacles, they decided not to show it because they all looked unconvincing. If Levinson had no solution for doing it without it looking fake to audiences, he wasn’t going to do it at all. It also kept the film in line with Warner’s cost-conscious approach. Imagination, Levinson rationalized, was scarier than obvious hardware.

Crichton was delightfully surprised by how much humor Levinson and the actors brought into the story. Test screenings skewed very negatively, forcing reshoots. Its Christmas 1997 release date was delayed to the dumping ground of February. The delay allowed Levinson to complete post-production on Wag the Dog and get it to theaters in December for Oscars consideration. Crichton wlso was involved in the re-shoot phase, as the story began to change.

The original ending, where the survivors form a pact to forget about the Sphere and deny any knowledge of awareness of its existence, is sometimes shown on television. In the theatrical release, their pact is shown to launch the Sphere into space, presumably flying back to its world of origin, or wherever it will likely be found by the spaceship 300 years into the future.

Despite star power and the intriguing subject matter, Sphere failed critically and commercially, only garnering $70 million in returns worldwide. Hoffman said that his last two films with Levinson didn’t have character depth in the script. Levinson and his actors were able to transcend the script issues with Wag the Dog but weren’t successful with Sphere. Although Hoffman accepted the role because working with Levinson was fun, he didn’t have as much fun making Sphere. This would mark their final collaboration in films.

Sphere ends up as a bizarre and disappointing misfire. Levinson combines 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Abyss, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, but couldn’t pull off the sense of wonderment that made those films work. Levinson reaches for unimagined heights and to awe viewers, but the obvious “villain” and ramshackle script elements never grip. Levinson claims he’d always wanted to do a sci-fi film, but it seems his lack of experience in the genre was a liability. Perhaps him stating that he didn’t want to show a giant squid because he didn’t know how to do it and not look silly was a giant red flag.

The biggest problem is lack of audience identification with Norman; he’s not very likeable. It’s also made my people too well-versed in science fiction and glosses over the significance of the events and the nuances of their implications. Still, Sphere isn’t as bad as its reputation as a bomb, but even low expectations will have few coming away feeling it a delightful surprise.

- In 2020, it was announced that Crichton’s “Sphere” would become an HBO Max series. “Westworld” writer and executive producer Denise The is scheduled to be the showrunner with “Westworld” showrunners Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan serving as executive producer. Robert Dpwney Jr.’s “Team Downey” production house would also collaborate.

Qwipster’s rating: C+

MPAA Rated: PG-13 for some startling images

Running Time: 134 min.

Cast: Dustin Hoffman, Sharon Stone, Samuel L. Jackson, Peter Coyote, Liev Schreiber, Queen Latifah

Small role: Huey Lewis

Director: Barry Levinson

Screenplay: Kurt Wimmer, Paul Attanasio, Stephen Hauser