Rocky III (1982)

Plans for a third Rocky film to round out the trilogy were underway during Rocky II‘s post-production. Stallone wanted to begin filming within 18 months so he wouldn’t appear too old. Bill Conti began composing pieces concurrently with his work on Rocky II.

Stallone envisioned using the original concept for Rocky II, with the final bout set in the Roman Coliseum, broadcast worldwide, against a goliath Russian opponent. Between training montages around Rome, Stallone planned funny fish-out-of-water moments of Rocky failing to adapt in Europe and poignant moments where Rocky visits the small villages in Italy where his father grew up. Apollo Creed would take over for a wheelchair-bound Mickey as his trainer. The story ends with Rocky using his prize money to retire to the old country.

Stallone worked on the first draft while promoting Rocky II, but personal issues caused delays. He suffered an ulcer from intense professional pressure, then returned to his philandering ways, moving in with model/actress Susan Anton, prompting his wife Sasha to file for divorce, seeking $5 million and custody of their two sons. After the relationship with Anton ended, Stallone reconciled with Sasha, flying her into Budapest, where he was filming Victory. Success surrounded Stallone with forbidden fruit, and he’d grown unhappy at home not indulging. He told Sasha they were spiritually linked and that she was the only woman who loved him as a lewd, crude nobody. True love means dependability and loyalty. Everything else fades but that. Stallone and Sasha moved to a new home in Pacific Palisades, California, hoping for a new start. (Sasha served as the production’s photographer again. She appears in the movie as a groupie who kisses Rocky and makes Adrian jealous.)

Stallone enjoyed seeing his face everywhere, unaware that it was eroding his self-image. He became someone he despised, succumbing to petty games and jealousy of what others had. Stallone describes this kind of fame as feeling like being locked in a room full of mirrors that show you so many different reflections of yourself that you lose sight of the real you. He began believing he was unbeatable and unstoppable, surrounding himself with opulence but at a cost.

Stallone grew resentful. Success didn’t solve his problems; it multiplied them. The public – including two presidents – saw him as Rocky, not Sylvester, and Rocky was an unrealistic image to match. It also typecast him into roles emphasizing his physicality, not his intellect. The only way to defeat the stereotype was to kill Rocky. He’d end Rocky’s trilogy with him on top, having achieved everything he wanted in life, dying in Adrian’s arms on the cab ride home with the crowds chanting “Rocky!” still in his ears after his Coliseum bout having endured the fight of his life.

He wasn’t sure Rocky dying was the ending he would choose. He had similarly contemplated Adrian dying in Rocky II but rationalized that the audience wouldn’t enjoy this and repeat viewings would suffer. He determined to shoot it anyway and decide later, though he then waffled on whether he’d return as director. Preparing for the fight scenes was exhausting, physically especially, but also mentally, with choreography and camera placements.

Still, he needed the money to keep from losing the material things in his life, and upon completing the draft, Stallone signed a contract for $2.5 million and 15% of the gross for writing, directing, and starring in the third entry. As they had to wait a year for all other principal actors to be available, Stallone signed to do a cop thriller titled ATTACK (later, “Hawks,” then finally Nighthawks), followed by a soccer-based drama, Escape to Victory (released as Victory).

When neither movie panned out financially, producer Irwin Winkler pumped the brakes on Stallone’s lofty ideas for Rocky III. Stallone’s stubbornness caused friction with Winkler, who reminded Sly that his success hadn’t born fruit outside of the Rocky series, and with MGM/UA financially struggling, they couldn’t afford to put all their chips on him. Stallone’s fans were fickle, and confidence was slipping. If Rocky III fell short, he could be driven out of the business. The Roman Coliseum title fight against the Russian goliath and Italian location shoot carried a massive price tag and thorny political hurdles. Stallone had contemplated shooting in New Zealand for these scenes, but that carried its logistical issues. Stallone would have to pull back substantially to assure Rocky III didn’t lose money.

As Stallone contemplated that his success was fleeting, he’d realized that fame and fortune had changed him. When he was a hungry nobody, he’d try anything short of suicide to make Rocky. Now that he had everything to lose if he failed, he was becoming safe and cautious in his professional decisions, and those decisions weren’t panning out. To remain on top, he needed that hunger back that money, fame, and women wiped away.

This self-analysis therapeutic exercise gave Stallone a better story idea. Rocky’s manager, Mickey, plays it safe, prolonging the heavyweight champion’s success, fame, and fortune. It all comes crashing down when he loses to a seemingly unstoppable force, as Rocky goes into an emotional spiral downward, overwhelmed by the feeling he’s been a loser this whole time. His wife Adrian and his rival-turned-friend Apollo see no other choice for Rocky but to regain his esteem again by reclaiming his championship. But to do that, Rocky has to grow as a fighter and regain the aspect that got him the championship: the hunger of a jungle predator – the “eye of the tiger.”

As Stallone continued to make Rocky III a metaphor for how he handled his meteoric fame and success, he incorporated more personal material. After Stallone’s longtime manager, Jane Oliver, had died of cancer in 1976, Stallone realized that she viewed it as her job to keep him happy. Without her there to protect him, all of the pitfalls and negative people quickly did him in. Similarly, Rocky’s manager, Mickey, would protect him, maintaining his championship with easy opponents.

As Stallone visited Las Vegas to scout Caesar’s Palace as a potential new location for his big fight, he met up with 38-year-old Muhammad Ali, who was set to make his fourth attempted comeback against undefeated champion Larry Holmes. For the fight, Ali had dropped 35 lbs. because he wanted to increase his agility and ability to dance around the ring like Sugar Ray Leonard to throw off Holmes. This angle inspired Stallone to develop a plotline of Rocky losing his title to a fiercer bruiser but comes back after learning to adapt his style to favor a leaner and more agile approach against an overpowering opponent.

Stallone grew close to Ali, asking if he’d be interested in taking over the Apollo Creed role, a character mostly modeled after him, in a move he felt would supercharge publicity for the film. After Holmes defeated Ali, Stallone, who knew Holmes well (Holmes was a regular at Stallone’s private gym at Culver City studios), offered him a smaller role as Rocky’s trainer.

Stallone, who’d dropped 50 lbs. to play his character in Victory, remained slim while adding muscle to look ripped yet lithe like Sugar Ray Leonard. Over the next ten months, he worked with a nutritionist to reduce his body fat as much as possible, cutting out sugar and eating nothing but whole grains, egg whites, and dozens of vitamin pills. His training emphasized his lower body, specifically running and jumping, to give him more stamina and dexterity.

Stallone felt that Rocky III should be as lean and agile as his body, with less dialogue and more action. The personal drama that got people to like Rocky was already well-established by the first two films. He could get right into the action, and the drama would unfold. Despite getting in the ring for three bouts, Stallone calls Rocky III a psychodrama more than a fight film. He pulled in viewer interest by making audiences want to see Rocky punch his opponents in the face for them.

In an early new draft, Rocky announces retirement after three years as the world heavyweight champion, hoping to get involved in a new career in Philadelphia politics. A street-tough young crusher named Clubber Lang challenges him to fight him before retiring, refusing to take no for an answer and mocking him publicly until Rocky relents. After Mickey, who had protected Rocky from certain defeats against opponents like Lang, suffers a stroke, Apollo Creed takes over the role of Rocky’s trainer and manager, teaching him to fight in an agile style, as well as how to invest his money to enjoy his retirement.

In addition to his physique, Stallone refined Rocky’s personality away from being an inarticulate slob who says, “Yo!”. Stallone knew many real-life championship boxers and noticed that many became civilized and sophisticated after achieving success. As the world champ, Rocky would want to project being a winner and would have worked on how he dresses and speaks, just as Stallone did when he became a successful actor. He followed a nutrition plan, hired a hair stylist, and had facial plastic surgery. He’s beaming with self-esteem rather than cling to the loser outlook when he has no money or future. This aspect carried to Adrian, as Stallone observed the fashionable turns for champion boxers’ spouses like Vicky LaMotta and Veronica Ali.

Reconfiguring the budget, Stallone renegotiated his salary, asking for $10 million but settling for $7 million. Burt Young also returned for the same can’t-refuse offer they’d made to keep him on board for Rocky II – six figures and a profit percentage. Talia Shire and Carl Weathers signed for a million dollars each. Stallone rationalized that fans wouldn’t buy Ali as Creed, though Ali graciously allowed the use of his Hancock Park mansion to serve as Rocky’s. Weathers was relieved he didn’t have to train to fight but still worked out every day.

For Clubber Lang, Stallone initially felt they wanted to cast a real boxer rather than an actor. After another attempt to cast Joe Frazier proved a bust because of his literacy problems, his top choice was Earnie Shavers until they began to spar. Shavers was holding back, refusing to hit Stallone with anything more than a soft jab. Stallone cajoled him into opening up and making it real, so Shavers demolished Stallone’s side with a left hook, driving his arm into his abdomen so hard that Stallone completely lost his breath and doubled over, wrenching in pain. In tears, Stallone could only sputter, “You nearly killed me!” before running to the bathroom to throw up. When it came time to read lines, Shavers’s voice seemed too soft. He wasn’t invited back.

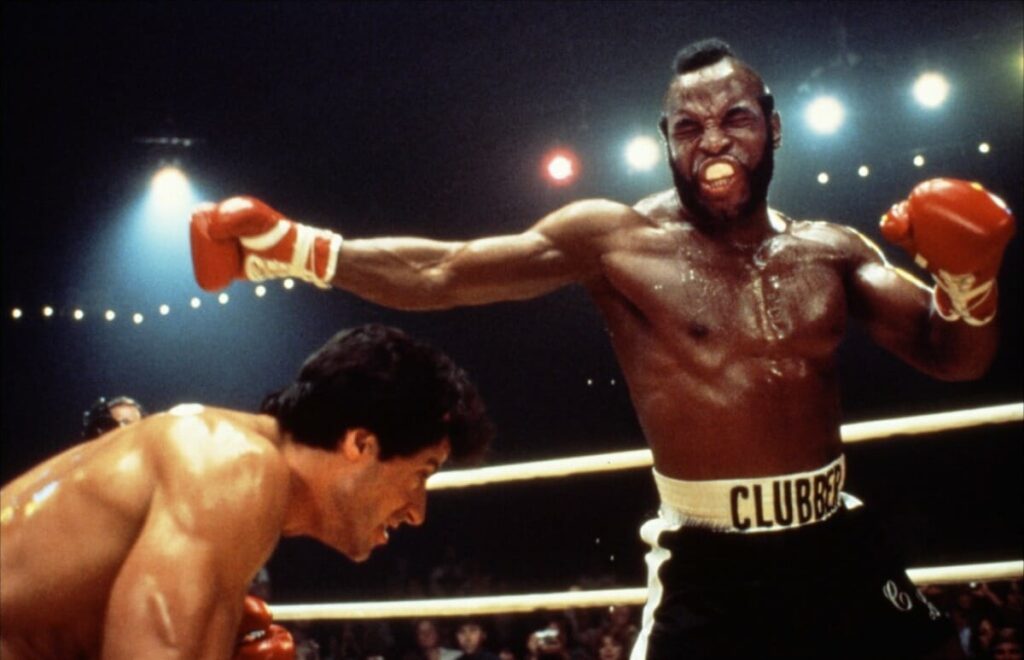

Also in auditions were ex-NFL great Jim Brown and WBC light heavyweight champion Matthew Saad Muhammad, but Stallone decided to give a nobody a break as he had. Over 1500 Black men, some from prisons, and the role ultimately went to Lawrence Tero, aka “Mr. T,” a former bodyguard for boxers Leon Spinks and Muhammad Ali, and celebrities like Steve McQueen, Diana Ross, and Michael Jackson. Mr. T had recently been named “Bouncer of the Year” for his stint at Dingbat’s Disco in Chicago. Casting director Rhonda Young discovered Tero from an NBC TV show called “Games People Play,” which included an “America’s Toughest Bouncer” competition where contestants broke through doors or threw dwarves like javelins.

Tero said he wanted any role that wasn’t a pimp, drug dealer, or another negative Black stereotype and borrowed money to fly to Hollywood to audition, memorizing the seven script pages containing his lines. Despite no acting experience, Mr. T felt an immediate connection to Clubber Lang as the embodiment of who he’d been his entire life. Stallone agreed, blown away by Mr. T’s authentic street attitude and surprising raw acting talent despite being a genuinely nice, thoughtful person under the menacing exterior. He was hired for $2500 a week (he cleared $32,000 altogether), beginning three months of physical training and nutrition to lose 30 lbs. The character was rewritten to match Mr. T’s persona, and T was allowed to rewrite his dialogue to what he was more comfortable with to maintain his force-of-nature intensity.

Hulk Hogan was cast as professional wrestler Thunderlips when Stallone was watching late-night cable TV and saw him wrestling four other men at Madison Square Garden. He thought it would be fun to include a scene where Rocky faces a wrestler in a charity mixed match, similar to when Muhammad Ali faced Gorilla Monsoon in 1974. When Hulk asked WWWF owner Vincent K. McMahon (Vince McMahon’s father) for ten days off to shoot the film, McMahon refused, resulting in Hogan quitting the wrestling organization to appear. After collecting $14,000 for the appearance, Hogan went to wrestle in Japan before joining the AWA in the US.

Mr. T and Hogan weren’t the only things generating publicity. An unexpected source came from a 12-foot-high (including pedestal), a 1500-pound bronze statue of Rocky with his arms raised in a victory pose. The statue was sculpted by Denver-based artist A. Thomas Schomberg is a specialist at creating sculptures of athletes in action. Stallone had previously purchased two Schomberg boxing sculptures from his exhibit at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas, “Mountain Rivera” and “Knockout,” and hired him to create a Rocky statue for two scenes atop the Philadelphia Art Museum steps made famous in Rocky. Stallone spent a week with Schomberg, allowing a plaster life mask of his face and posing for over 800 pictures. The first sculpture was a 28″ reference model that Stallone asked to be altered because it looked too beefy after he had considerably toned up in the weeks that followed since posing.

After chiseling the model to Stallone’s liking, Schomberg built a larger statue for use in the film. Schomberg’s contract also allowed him to make eight busts plus two other full-sized statues to sell. One full-sized was sold to businessman/sports enthusiast Robert Breitbard, who displayed it at the San Diego Hall of Champions Sports Museum until 2017, whereupon it was acquired in auction by Stallone for over $400,000. The third statue wasn’t cast until 2006 by Schomberg for auction, though it has failed to sell at the asking price in the low millions. In 2024, Stallone loaned the second version to the Philadelphia Art Museum to use on top of the stops temporarily (to save money on moving the first) for its first annual “Rockyfest” celebration.

For a tax write-off donation, Stallone told the Philly bureaucrats that the statue used for Rocky III could remain there because fans regularly ran up the steps re-enacting the famous scene in the original Rocky. The statue would be a magnet attracting common people to check out more art inside the museum.

Controversy ensued when the Philly Art Museum Commission proclaimed the statue too garish to remain beyond the two weeks needed for the film. Having a promotional prop for the sequel to sequel to a movie as the first thing you see when visiting the Art Museum seemed in bad taste, and they said they would negotiate to subsequently house it in the JFK Plaza tourist center or the Philadelphia Spectrum, where objects to promote the city or its sports belonged. Stallone was incensed they rebuffed his generous offer and, after the three days of shooting was concluded, he shipped it to his home in California, where he tied it to a backyard tree until he determined what to do with it.

Philadelphians circulated petitions to bring the statue back. Local politicians got involved, offering bills to house the statue in town. Stallone offered to return the statue free of charge if the commission reversed their decision. The commission ultimately agreed to display the statue at the museum during the film’s promotional period before it found a semi-permanent home at the Spectrum. Good enough. However, the film production didn’t return for the statue, leaving the art museum paying $12,000 for the removal and moving costs.

As a director, Stallone employed a different vibe for Rocky III. Rocky II emulated John Avildsen’s style because it was set directly following Rocky, three years have passed since the events of Rocky III. As Rocky became sophisticated, Stallone wanted that style to carry into the look and tempo of the movie. Rocky, Adrian, and company were always in the public eye. The film should feature more news footage, plus Steadicam’s work that gave a documentary vibe, as if Rocky lived in a fishbowl, always watched. Rocky’s problems used to be his own; now they are front-page news followed by millions around the world.

In later interviews, Stallone softened on the possibility of Rocky IV, perhaps continuing as a character study of Rocky outside of the boxing arena. Perhaps Rocky could get into social service or politics or might center on the further friendship between Rocky and Apollo Creed, a footloose and fancy-free “Butch & Sundance”-type adventure. But he doubted he would, saying he loved the character too much to see him bleed dry. He’s not a Frank Capra character that can go on forever.

Because of the weeks of pre-rehearsal for the boxing scenes, the shoot was only 37 days and came in $1.6 million under budget. The big bout took 5 days to film for Rocky and 9 days for Rocky II but only took seven hours for Rocky III because they’d rehearsed the moves and camera placements based on fourteen pages of blow-by-blow details Stallone devised beforehand. As with Rocky II, Stallone wanted some real punching, resulting in authentic bruises and blood on their faces. Paramedics stood by with oxygen, smelling salts, and IV units. Stallone says everything from the middle of the final round to the end is them fighting.

For the music, Stallone had cut the opening montage to Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust,” but they wouldn’t grant him the rights. Stallone’s cycled through alternates. He liked “Poor Man’s Son” by Survivor and contacted Survivor’s Jim Peterek to deliver a similarly raw, pulsing song that matched the montage and the film’s themes. Stallone FedExed a Betamax of the opening montage with Queen’s song on it to Peterek, who had bandmate Frank Sullivan to assist. They turned the sound down and came up with a similar beat to coincide with every punch. Struggling for what the song’s lyrics should be about, they requested a rough cut of the entire film. Stallone reluctantly agreed, on condition they return it overnight delivery one day later. They keyed in on the film’s vibe and recurring phrase, “eye of the tiger,” and the lyrics fell into place. “Eye of the Tiger” hit #1 on the pop charts and remained there for seven weeks.

The release date was moved up two weeks to May 28 instead of June 11. MGM/UA needed an immediate influx of cash, and Rocky III was the only sure thing they had on the horizon.

Intending it to be the last Rocky film, Stallone broke down sobbing when production wrapped. He felt he was losing his best friend, his therapist, his sounding board, his Aladdin’s lamp, and his safety net for a career that hadn’t panned out beyond Rocky. Rocky, to him, was his creation – his child – a child that gave birth to the man Stallone became. Rocky taught Stallone valuable life lessons, especially by setting standards and values that he was failing to live up to.

Rocky III was hugely successful, outgrossing the prior films and only bested by E.T. among 1982’s top-grossing films. While certainly entertaining, Rocky III loses some of the heart, soul, and focus of the Oscar-winning first entry. In place of character drama is a mostly commercial vehicle using the same characters, given a simplistic revenge plot rarely found outside of a wrestling arena. Fittingly, future WWF champion Hulk Hogan is a harbinger for a series that takes a professional wrestling vibe henceforth. Hogan exits the film, but the bombastic spirit remains as Mr. T and Balboa face off in two boxing spectacles.

Stallone’s going lean and clean became a philosophy of his movie. Rocky III is twenty minutes shorter than its predecessors but beefed up with action and confrontations. Character progression proceeds simply: Adrian shows spunk, Rocky, fear, and Apollo, a champion’s character. The rest is machismo and braggadocio, as Clubber Lang has, literally, no character development beyond his insatiable quest for the championship. It’s the first time that a true villain has been introduced into the series, possessing no redeeming features whatsoever.

Although simple and predictable, Rocky III still delivers excitement. It’s slick, polished, and engaging. Viewers who prefer action to romance might consider it the most entertaining entry, just as Rocky extinguishes softness to face Lang, gentleness, and humanity in favor of machismo. Whereas Rocky‘s pugilists were defined by the hearts beating within each fighter’s chest, Rocky III is measured by how hard the fighters externally beat their chests with their fists.

Qwipster’s rating: B+

MPAA Rated: PG for language

Running Time: 99 min.

Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Carl Weathers, Mr. T, Talia Shire, Burgess Meredith, Burt Young, Hulk Hogan

Director: Sylvester Stallone

Screenplay: Sylvester Stallone