Jungle Fever (1991)

Spike Lee (Clockers, He Got Game) tackles the racism issue head on once again with his provocative drama, Jungle Fever, which deals with the complications of an interracial relationship in the racially charged environs of metropolitan New York. Although not as commanding as Do the Right Thing, Lee continues to mix heady commentary and wit into the more serious themes, and the result is a film that fosters deep thought in between the entertainment. Like most of Lee’s works, your mileage will vary as to how much of this potent political concoction speaks to you, but even if you find yourself in disagreement with most of the positions offered by the many varied characters, it does make you think deeper than similar films of its ilk.

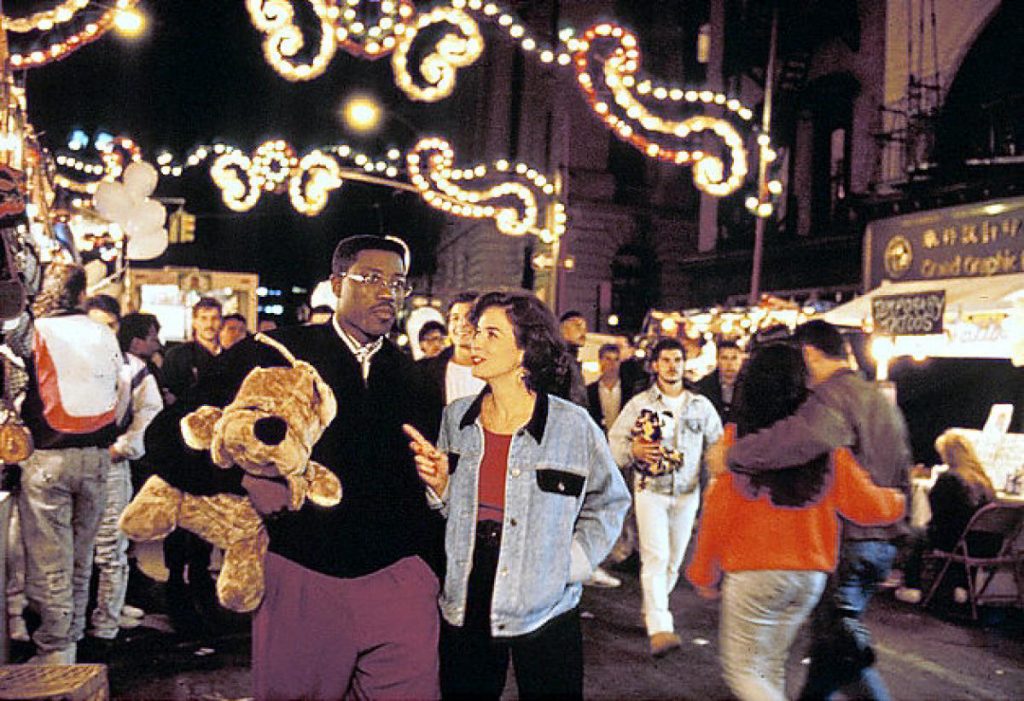

Wesley Snipes (Major League, Blade) stars as a successful Harlem architect named Flipper Purify, married to a wonderful wife (McKee, Lift), father of a precocious daughter, and looking forward to the prospect of finally becoming a partner in his nearly all-white architectural firm. That firm has given him a new temp secretary, an Italian-American named Angie (Sciorra, The Hard Way), and though the two don’t have a great deal in common, they end up having a sexual affair, with the promise of more. Unfortunately, both confide in their respective best friends, and word spreads, which doesn’t sit well for their established relationships, their families, or their neighborhoods. They become pariahs for their relationship, and though there is nothing bad between them to suggest they don’t have a thing, the mountain of societal pressures prove to be quite daunting.

Lee continues to blend vivid color schemes, choice music, and rich cinematography to create a visual smorgasbord of people and places in New York City that contrast the complexities of the ethnic melting pot that never quite has been able to mix. The Blacks of Harlem and the Italians of Bensonhurst are seen as almost completely segregated, with Angie not only never having been to Flipper’s area of residence, he’s actually the first person she’s actually met from there, despite being mere miles apart. On both sides, there is a great emphasis on the family unit, and particularly how one’s upbringing shapes the opinions of the children, and the continuance of racist feelings that have been passed down from generations. Although everyone bites their tongue in discussing these feelings openly to someone of the other race, once that person leaves the room, those of similar ethnic backgrounds show their true colors, and discuss just how much “those people” make them sick.

Lee also continues to employ music as a means to effect mood which can make a good scene great by the right punctuation of mood. It’s a bit of a mixed bag as used here. Stevie Wonder provides most of the film’s soundtrack, and Lee is very comfortable in selecting just the right songs for the right scenes. He even tosses in a few choice tracks from Frank Sinatra for good measure. Lee’s favorite future composer, jazz man Terence Blanchard (Barbershop, People I Know), gives his first rich and memorable score, but it’s not always congruous with the tone of the conversations at hand. Some scenes meant to be light have a very somber feel due to the slow and contemplative piece of music that coats the scene. And when I say coat, I mean that — it’s sometimes hard to get into the conversations when there is unnecessary music played over it, especially when that music doesn’t really play well to that scene.

The romance that brews between Flipper and Angie never quite smacks of the kind of passion that suggests that their relationship would ever have progressed beyond a one-time fling, but Lee keeps it on the real by never exploring the relationship with any sort of depth. They never have anything but curiosity and mutual attraction. Snipes gives a good performance considering he is miscast as a somewhat reserved buppie, and Sciorra is adequate enough. The acting does encroach into hammy territory on occasion, especially in showcasing Flipper’s Baptist parents, and the Italian gang of idiots at the local malt shop.

Jungle Fever also suffers from an unnecessary plot revolving around Flipper’s older brother, a crackhead named Gator (Jackson, Goodfellas), who is constantly coming around to beg money from his doting apologist mother (Dee, American Gangster) and the brother who just wants him out of his face. Eventually, these developments finally come to a head when Gator grows increasingly more hostile in his tactics in order to get money from his family, leading to an eventual tragedy that seems a bit more melodramatic than necessary to get the point across. It’s not that this storyline is bad, it just diverts from the main story and its themes, and probably should have been its own movie altogether.

As it stands, Jungle Fever is an uneven movie, but the strong points vastly outweigh the weaker elements sufficiently that it retains its status as a good film. The story isn’t so much about overt racism toward another ethnic group so much as it is about the brutal restrictions of each individual ethnic group towards its own kind in keeping them from fraternizing with the “wrong” crowd. Although segregation is still a thing of the past from a legal standpoint, as evidenced by Lee’s poignant, controversial drama, at the end of the 20th century, it’s still alive and well in the hearts and minds of many.

Qwipster’s rating: A-

MPAA Rated: R for strong sexuality, nudity, drug use, violence and language

Running time: 132 min.

Cast: Wesley Snipes, Annabella Sciorra, Samuel L. Jackson, John Turturro, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Spike Lee, Lonette McKee, Anthony Quinn, Frank Vincent, Nicholas Turturro, Halle Berry, Tyra Ferrell, Tim Robbins, Brad Dourif, Veronica Webb, Veronica Timbers, Michael Imperioli, David Dundarra, Steve Randazzo, Joe D’Onofrio, Michael Badalucco, Anthony Nocerino, Debi Mazar, Theresa Randle, Queen Latifah

Cameo: Doug E. Doug

Director: Spike Lee

Screenplay: Spike Lee